I was never a Daft Punk fan until Random Access Memories, and it had to do with a shallow perception of the band as gimmick musicians: robot masks, huge waiting periods between albums (the better to push the product), a unified aesthetic that didn’t ring genuine, but as carefully branded as a corporate logo. And then the music, of course! Tinny, relentlessly circuitous, lacking the punch of what I considered house music or the chops of rock, and these days, sounding extra-flat in the face of the zeitgeist-defining drop of dubstep. Daft Punk’s music in this context was their number-one gimmick: small, repetitive sounds, set in motion, with the weight and gravitas of a music box.

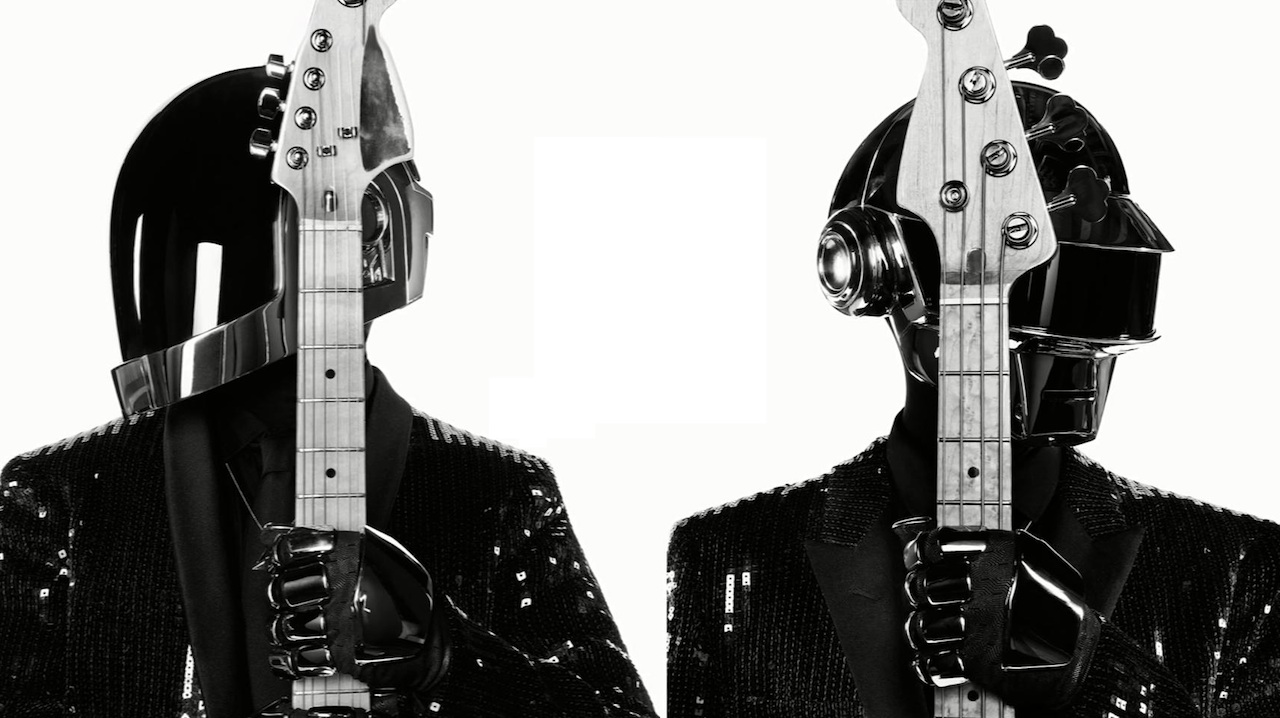

Well, duh, and the great, surprising thing about Random Access Memories is how it turns all of these assumptions on their head–doubling down on the mask thing, for example (Leather-ier! Sleeker! Shinier! [stronger better faster etc]), coming out of the gate with the decidedly un-2013 single “Get Lucky,” carefully placed TV and Coachella advertisements. What this overlooks, however, is the necessity of these items to not just The Music, but The Band. Dismissing Daft Punk for the masks is like dismissing the White Stripes because you thought they were brother and sister.

Well, duh, and the great, surprising thing about Random Access Memories is how it turns all of these assumptions on their head–doubling down on the mask thing, for example (Leather-ier! Sleeker! Shinier! [stronger better faster etc]), coming out of the gate with the decidedly un-2013 single “Get Lucky,” carefully placed TV and Coachella advertisements. What this overlooks, however, is the necessity of these items to not just The Music, but The Band. Dismissing Daft Punk for the masks is like dismissing the White Stripes because you thought they were brother and sister.

But this is 2013 and I should push myself more, right? So I crash-coursed the Daft Punk catalog. This is probably painfully obvious to long-term, die-heard fans, but here’s what struck me in one go through their catalog: they are undoubtedly the most influential band of the past two decades. A LOT of things began to make sense–everything from chill-wave to dubstep, Girl Talk to cloud rap, Chromatics to the Knife, any band with masks and half-mysterious unified aesthetics, the over-the-top stage shows of every electronic act and DP-influenced band (even equally-iconic Radiohead), the pseudo New York-disco revival that largely occurred without direct influence from Daft Punk, primarily executed by LCD Soundsystem, a band of disco LARP-ers that seemed intent on making Homework‘s excellent “Teachers” into a career-move.

With all of Daft Punk’s post-Homework music, movies, tours, and film scores, the further they moved away from house music, the more they took on a proto-mash-up position of subsuming the entirety of modern music–rock and roll, dance, disco, sampling–into a single, definite object.

The band ruffled feathers when they made comments about the prevalence of digital technology and its effect on creating music. Read one way, their position scans as elitist, and a profound example of Missing the Point–as the story goes, the democratization of movements is always good. Maybe this is a distinctly modern, pseudo-egalitarian, and yes, naively American idea.

Daft Punk’s comments were really a subliminal attack on the bedroom-music phase–not on technology and everyone having the same tools, but on the type of laziness that breeds when people are told they can do anything, and by virtue of having the ability to do anything they should do it, and by virtue of doing it, they are doing it well (or doing it right, as Panda Bear might say).

This is false, and not to ascribe some grand political importance to it, but it seems to me like a good idea to let certain people play their part. If indie music has been weary and same-y and deadening recently, maybe it has something to do with everyone trying their hand at making the same kind of music in the same way: vaguely druggy, too cool for a melody, delivered with just a hint of enough insight to appear deep or meaningful, as if minimalism is intrinsically profound (this mentality seeps into other genres too). We should enjoy the democratization of technology, but a democracy means we kind of end up picking “the best,” no?

This is false, and not to ascribe some grand political importance to it, but it seems to me like a good idea to let certain people play their part. If indie music has been weary and same-y and deadening recently, maybe it has something to do with everyone trying their hand at making the same kind of music in the same way: vaguely druggy, too cool for a melody, delivered with just a hint of enough insight to appear deep or meaningful, as if minimalism is intrinsically profound (this mentality seeps into other genres too). We should enjoy the democratization of technology, but a democracy means we kind of end up picking “the best,” no?

Random Access Memories is defined by what happens when an artist has the confidence to dream big and then act big. On paper, these guests feel like a mess. In execution, it’s the most immaculately executed roster of musicians in some time, a perfect act of curation, mixing together not just big, genre-criss-crossing names like Pharrell and Julian Casablancas and Panda Bear, but also nameless session musicians who have worked with pop’s biggest stars. It makes other records, and their quaint adherence to genre, sound slight.

If I’ve always thought of Daft Punk as gimmicky, repetitive, and “small,” it’s tempting to hold onto these accusations: what’s more gimmicky than overt genre cross-pollination, oversized but under-stuffed ambition, shiny new masks, and a slick rollout of new material? But a music box is the most honest musical medium: you pick it up, admire its outer artistry, pop it open, focus on the repetitive but direct music and its trance-like effect, and the “thing” itself only reinforces the music. You can’t hear the music without opening the box, just like you can’t really hear Random Access Memories without sitting down and having it wash over you in one go, a front-to-back, capital-A Album, shiny new masks and all. If “Get Lucky” sounds small, and Nile Rodgers’ guitar a cheap, a wind-up toy riff layered with Pharrell’s potentially-corny falsetto, I’d suggest that’s the point? Random Access Memories sounds like Daft Punk playing a tongue-in-cheek version of Gloria Swanson from Sunset Boulevard: it’s the pictures that got small.

If I’ve always thought of Daft Punk as gimmicky, repetitive, and “small,” it’s tempting to hold onto these accusations: what’s more gimmicky than overt genre cross-pollination, oversized but under-stuffed ambition, shiny new masks, and a slick rollout of new material? But a music box is the most honest musical medium: you pick it up, admire its outer artistry, pop it open, focus on the repetitive but direct music and its trance-like effect, and the “thing” itself only reinforces the music. You can’t hear the music without opening the box, just like you can’t really hear Random Access Memories without sitting down and having it wash over you in one go, a front-to-back, capital-A Album, shiny new masks and all. If “Get Lucky” sounds small, and Nile Rodgers’ guitar a cheap, a wind-up toy riff layered with Pharrell’s potentially-corny falsetto, I’d suggest that’s the point? Random Access Memories sounds like Daft Punk playing a tongue-in-cheek version of Gloria Swanson from Sunset Boulevard: it’s the pictures that got small.

Consider that most of the reference points on this album are long-playing records that may sound stuffy in 2013, but were blockbusters in their time of the late ’70s and early ’80s. And consider that these same records can be found for less than $5 in just about every record store. Daft Punk are recycling mainstream sounds and “art”ing them up, not out of novelty but genuine inspiration. Where the never-ending search for obscure sounds to crib from is something a lot of modern artists succumb to, Daft Punk and RAM are taking the opposite tack, and in this is something really beautiful.

As Paul Williams sings on “Touch,” “you’ve given me too much to feel.” On record, it’s a literal recollection of a non-human “feeling almost real,” but in context of Daft Punk as musicians, and we as listeners, it’s a metaphorical recollection of being “touched” by the records of our youths, the sounds of the records our parents listened to, and the heightened, pop-up-book sensation of feeling and being young and in love with music.