“I feel like ‘the end of the fucking world’ is a common phrase in a teenager’s life,” cartoonist Charles Forsman observes via email, taking some time between busily filling orders for his small press publishing company Oily Comics, and preparing for the release of TEOTFW, a terse, touching graphic novel out via alternative comix behemoth Fantagraphics as of this week.

“If you search on Twitter for ‘the end of the fucking world’, you will get tons and tons of what I think must be teenagers using this phrase.” The Hancock, Massachusetts-based cartoonist continues: “Because that is the thing right? When you are a kid, everything really is the end of the world. The future is so painfully far away and you are so impatient that whatever is happening right now that it is all that matters.”

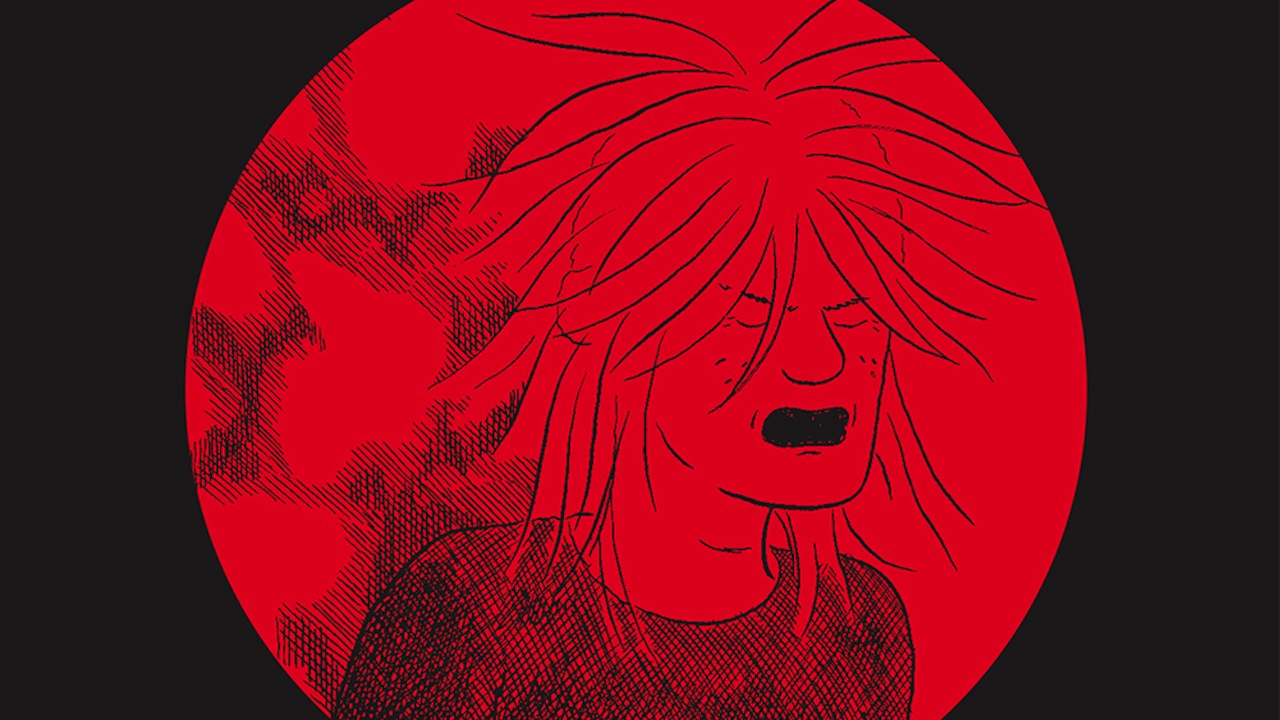

TEOTFW (yes, The End of The Fucking World) expertly channels that adolescent-to-early adult frustration. The 176-page comic book follows James, a 22 year-old sociopath trying really hard not to be one anymore because he’s kind of in love, and Alyssa, 17, smarter than her age but still full of c-word dropping rage, as they amble across the country, chilling out in beyond-boring small towns, hitching rides with creeps, stealing cars, and in a particularly knotty tangent that also involves shirtless knife-throwing, meeting up with Alyssa’s deadbeat dad. At some point, Satanists stomp into the plot – an outside force pulling the already embattled couple in “us against the world” mode closer together.

Forsman’s narrative occupies a tangible metal/punk milieu in spirit as much as in quick signifiers like hoodies or homemade tattoos. Movies like the Keanu Reeves-starring hesher crime flick River’s Edge or Dennis Hopper’s punk spleen vent Out of the Blue come to mind–subculture-aware art that doesn’t let its screw-up protagonists off the hook, but sees larger societal forces at work making these kids feel so damned alone, and isn’t too happy about it.

Forsman’s narrative occupies a tangible metal/punk milieu in spirit as much as in quick signifiers like hoodies or homemade tattoos. Movies like the Keanu Reeves-starring hesher crime flick River’s Edge or Dennis Hopper’s punk spleen vent Out of the Blue come to mind–subculture-aware art that doesn’t let its screw-up protagonists off the hook, but sees larger societal forces at work making these kids feel so damned alone, and isn’t too happy about it.

Alyssa, a teen who bolted from home to avoid an ineffectual mom and moms’ “pervert boyfriend,” is wise beyond her years: the Ghost World girls if they had as many problems as they do snarky jokes and first world problems. And James, a painfully sincere scrapper and survivor with nobody else, is afforded a past that most mysterious drifter characters usually don’t receive: His mother took her own life when he was four, he began killing animals at 13, his dad seems like a pretty awful human being. Forsman describes TEOTFW as “Two broken people forever failing to fix each other.” Alyssa, in TEOTFW‘s Tumblr-rant poetic narration, frames their relationship like this, “I think I love him. The boy needs someone.”

A cartoony, almost daringly cute, yet confident drawing style that focuses on making as few marks on the paper as possible – the existential adorableness of Peanuts seems like a good entry-level precedent – adds charm to the romance and actually makes the violent emotions even more disturbing. And there are just delightful moments of pause in this book, which reach a melancholy fever pitch because, as you might imagine, this book doesn’t exactly end well: Alyssa staring at a cat in close-up, the cat’s whiskers lovingly rendered as thin nervous lines; James and Alyssa in the back of a pickup truck with endless, flat nothing spreading out behind them.

Upon breaking into a home and squatting, Alyssa locates an LP with the song “Frankie & Johnny” on it. She throws it on the turntable and does a rubbery dance to it, while James maniacally head bangs. Forsman moves the joyous sequence across two pages, the murder ballad’s lyrics dancing atop their heads, frozen dance contortions filling up the panels. Cute romantic quirk and real life awkwardness slamming into each other.

“I think those images are from me watching Tarkovsky and Malick movies,” Forsman, who was exposed to work by those gritty, arty filmmakers at a young age by way of a movie-director brother, Zak, explains. “I have always liked the idea of simple characters against slightly more realistic backgrounds. I think it creates and uneasiness that I like because it shouldn’t go together, but it does.” And then typically, like his honest, unpretentious characters, he hesitates to get too heady, even if he did just drop a reference to Tarkovsky. He locates a more down-to-earth comparison for his low-key unreal vision. “You know, it’s like Roger Rabbit or something?”