The Village Voice, an alt weekly that has been steadily suffering from a mass expulsion of journalists (and relevancy), was handed a great scoop: an exclusive interview with Banksy. Journalist Keegan Hamilton says he conducted the interview over email.

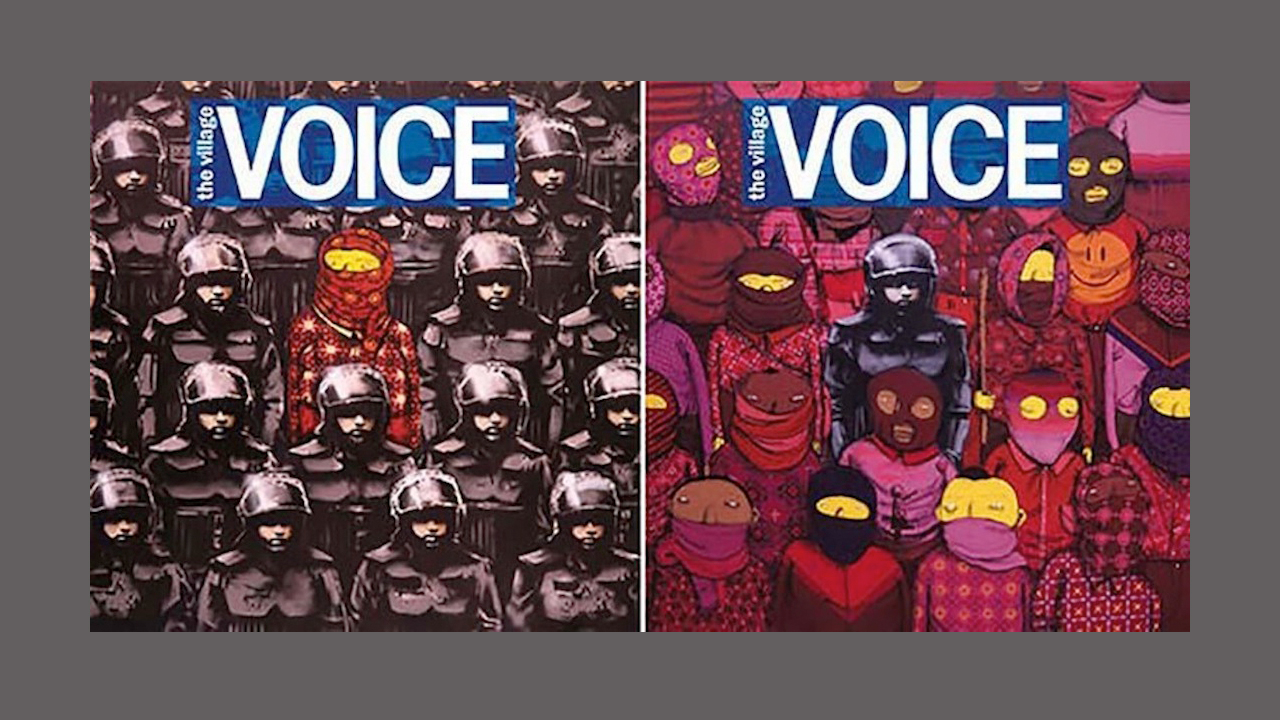

It was set up by Jo Brooks, Banksy’s bonafide publicist. In addition to dishing details about Better Out Than In, he gave the paper cover art that was reproduced from a pair of paintings he did with Brazilian twins Os Gêmeos. You can read the full article HERE or just scroll below for the best nuggets.

First off, everyone should stop speculating and trying to get all deep about his intentions for Better Out Than In:

“There is absolutely no reason for doing this show at all. I know street art can feel increasingly like the marketing wing of an art career, so I wanted to make some art without the price tag attached. There’s no gallery show or book or film. It’s pointless. Which hopefully means something.”

He began to recon spots a few months ago, plans on staying for a bit, and doesn’t really have the 31-day art campaign completely planned out.

Banksy says he visited New York “a couple of months ago” to scout locations for the October show, but he “returned to find most of the empty lots I planned to use have got condos built on them already.” He is now living in the city—not surprisingly, he won’t reveal where he’s holed up or how long he plans to stay—and he hints at a lack of a formal plan for when and where new pieces will be installed this month.

“The plan is to live here, react to things, see the sights—and paint on them,” he writes. “Some of it will be pretty elaborate, and some will just be a scrawl on a toilet wall.”

Here’s how he came up with “The Musical” series:

The idea to make a stencil saying ‘The Musical’ only came up when I saw the ‘Occupy’ graffiti.”

Banksy says he made a mistake in 2008 by doing an exhibit that lacked actual graffiti and for subcontracting others to do his art for him.

“I totally overlooked how important it was to do it myself,” the artist says. “Graffiti is an art form where the gesture is at least as important as the result, if not more so. I read how a critic described Jackson Pollock as a performance artist who happened to use paint, and the same could be said for graffiti writers—performance artists who happen to use paint. And trespass.”

With success comes lots of baggage, both his and other people’s:

“I started painting on the street because it was the only venue that would give me a show,” he writes. “Now I have to keep painting on the street to prove to myself it wasn’t a cynical plan. Plus it saves money on having to buy canvases.

“But there’s no way round it—commercial success is a mark of failure for a graffiti artist. We’re not supposed to be embraced in that way. When you look at how society rewards so many of the wrong people, it’s hard not to view financial reimbursement as a badge of self-serving mediocrity.”

Banksy notes the transformative nature of art when you put it on the street and then sell it in a gallery setting.

“Obviously people need to get paid—otherwise you’d only get vandalism made by part-timers and trust-fund kids,” Banksy says. “But it’s complicated, it feels like as soon as you profit from an image you’ve put on the street, it magically transforms that piece into advertising. When graffiti isn’t criminal, it loses most of its innocence.”

And the kicker:

“New York calls to graffiti writers like a dirty old lighthouse. We all want to prove ourselves here,” Banksy writes. “I chose it for the high foot traffic and the amount of hiding places. Maybe I should be somewhere more relevant, like Beijing or Moscow, but the pizza isn’t as good.”