2008 was not that long ago. In the evolution of gay acceptance in America, however, 2008 was effectively a generation ago. Since 2008, the moral, political, legal and societal conversations around homosexuality have dramatically shifted in favor of us gays — in the mainstream, at least. For minorities, it’s a different story. Being Indian-American, I still have to balance the Indian diaspora and their understanding (or lack thereof) of queerness.

Many great pieces of South Asian literature that talk about queerness focus on the time someone is realizing she may be gay. In other words, they’re coming of age stories. As someone who was personally confident in my own identity, I knew I was not a coming of age story. I knew, however, that what I needed (indeed what many South Asian queer people need), was not a story about coming out to oneself. Rather, we needed a story about balancing our queer identities in places like NYC with our queer identities to our family.

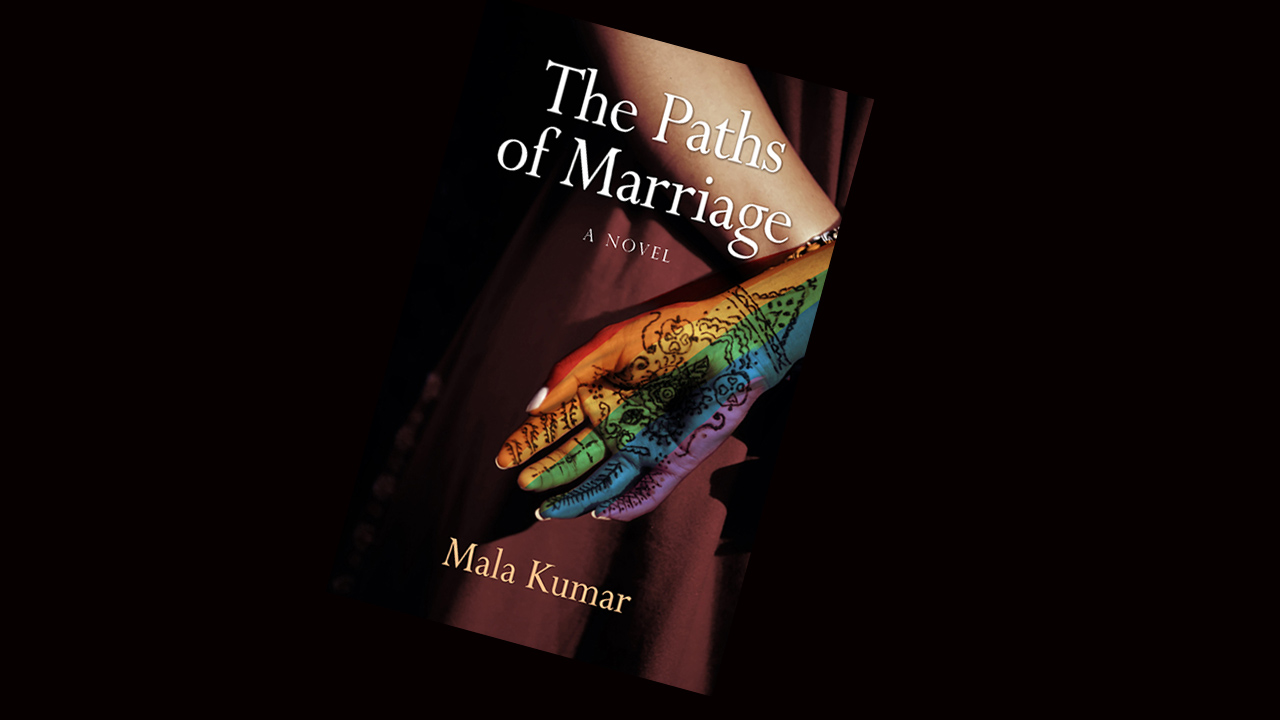

One of the reasons I wrote my debut novel, The Paths of Marriage, was to fill this gap. The story follows three generations of Indian and Indian-American women, the last of whom is gay. Deepa, the gay character, starts her story in 2008 in NYC. Like me in that era, Deepa was confident she was a gay Indian woman. Also like me in that era, she was not confident in revealing to her Indian family that she was gay.

While current mainstream America now largely understands that one’s sexual orientation can be fluid, the Indian community often writes off homosexuality as a phase. Even South Asian gay literature, most of which focuses on a character’s realization that he or she is gay, leaves the possibility that their sexual orientation could change back. I knew in writing The Paths of Marriage that I needed a character who was not ambiguous or uncertain in her orientation. I needed a character who was not coming of age, but rather figuring out how to balance the disconnect between being queer in NYC and being of Indian origin.

Back when I first moved to NYC in 2008, this same disconnect followed me around everywhere I went. In my romantic life, the prospect of a potential partner ended after one date following this typical conversation:

Her: When did you come out to your parents?

Me: I haven’t. You?

Her: You haven’t? When are you planning on coming out to them?

Me: I don’t have any plans. It’s complicated being of Indian origin.

Her: I see.

I lost count how many times I discovered the words, “I see” was code for, “I guess this relationship can’t go very far, then.” Even in a city as diverse as NYC, there still exists a queer mainstream. Those I dated who were part of that queer mainstream found it hard to grasp the cultural implications of coming out to an Indian family. Marriage, extended family and community opinions are paramount in South Asian society, and being queer does not fit in with that paradigm. I may have been living in the same city as my mainstream queer dates, but my cost-benefit in coming out to my family was vastly different.

In mainstream New York media, pop culture, and socializing, the idea of coming out to everyone was equated with being courageous. Most New Yorkers felt I could not be confident in my gay identity until I came out to my family. As the out = courageous formula took root across the country, the rift in my gay Indian identity grew.

Writing The Paths of Marriage was cathartic. I created a story that was entirely fiction but true in my own feelings. I finally chose to come out to my parents once I knew I wanted to publish The Paths of Marriage. In doing so, I revealed to them that I had developed an entire life in New York City that revolved around being gay. Countless hours of conversation and reflection had already gone into my steady New York City queer identity, even if New York City wasn’t always able to fill the gap in my identity. Indeed, when I came out to my father – who was born and raised in India – he replied that he had no frame of reference of what that actually means. I later gave him a draft version of The Paths of Marriage. Once he finished reading the book, he wrote back with one simple message: “I get it now.”

So, while New York City has been instrumental in me solidifying my queer identity, it took a bit of exploration to figure out how to balance that with being Indian. Even in a city like New York, there is a mainstream for everything, and the mainstream is not indicative of those of us who have another layer to handle. In focusing on a story that is not coming of age, I was able to capture one aspect of this not mainstream NYC queer identity. Doing so has helped me bring to the Indian community the idea that while we are Indian queers can be fluid, we are also solid.

The Paths of Marriage is now available everywhere books are sold. Join Mala on Saturday, April 18, 2015 at the Rainbow Book Fair, and on Sunday, April 19, 2015 at Bluestockings for readings, Q&As and discussion on the novel and her work with the United Nations.

(Photos: Mala Kumar)