ANIMAL’s original series I Should Have Shot That! asks photographers about that one shot that got away. This week, we talk to actor, stuntman and photographer Dean Neistat about his days of as an Air Force aircraft commander.

After Hurricane Sandy, a lot of people are very surprised by some of my photographs, my brother’s photographs, my brother’s videos, and they look and they say “How can you do that? It’s so dangerous! Don’t get hurt!” We just don’t see it that way, because we come from a different body of life experiences. We know the difference between an actual dangerous situation versus a perceived dangerous situation. And I’m very good at separating the two and identifying the two.

“Oh what if… what if.. what if… what if?” Everybody gives the “what if” and I’m like, “I’m here, so what if doesn’t matter.” The only time when I felt in danger was when we were on the East Side and I crossed the FDR to help a guy out of a car who was stranded in the rising water. It was dangerous because the winds on the East Side were stronger than anywhere else in the city. I saw the potential of being blown over or falling down or getting hit by something then. The rest of the night, everywhere else we went, we didn’t go anywhere near scaffolding because that was down all over the city, and as far as stepping into a pothole… you could see the bottom of the water. I maybe hit my shin on a park bench once, but I didn’t see many opportunities that night where we could have been injured or put in real danger.

I flew a C-17 for seven years. I took loads of pictures…

The more dictatorial countries have really interesting cityscapes from the sky at night. Saddam was great at it. In Belgium and Denmark, they use hydroponic greenhouses a lot, everywhere, and at night they’re lit up like nothing you’ve ever seen. You’re seven, eight miles above the Earth looking down, and all you see are these incredibly bright lights in little perfect squares dotting the countryside… Photos of loading in a sandstorm, where you can’t see any faces because you can barely breathe unless you’re covered up and you have big, thick, black goggles on because the sun is so bright in the Middle East. Loading in Iraq at night under NVGs, when there’re no lights anywhere on the ramp because if you turn on the light, they’re going launch a rocket at you…

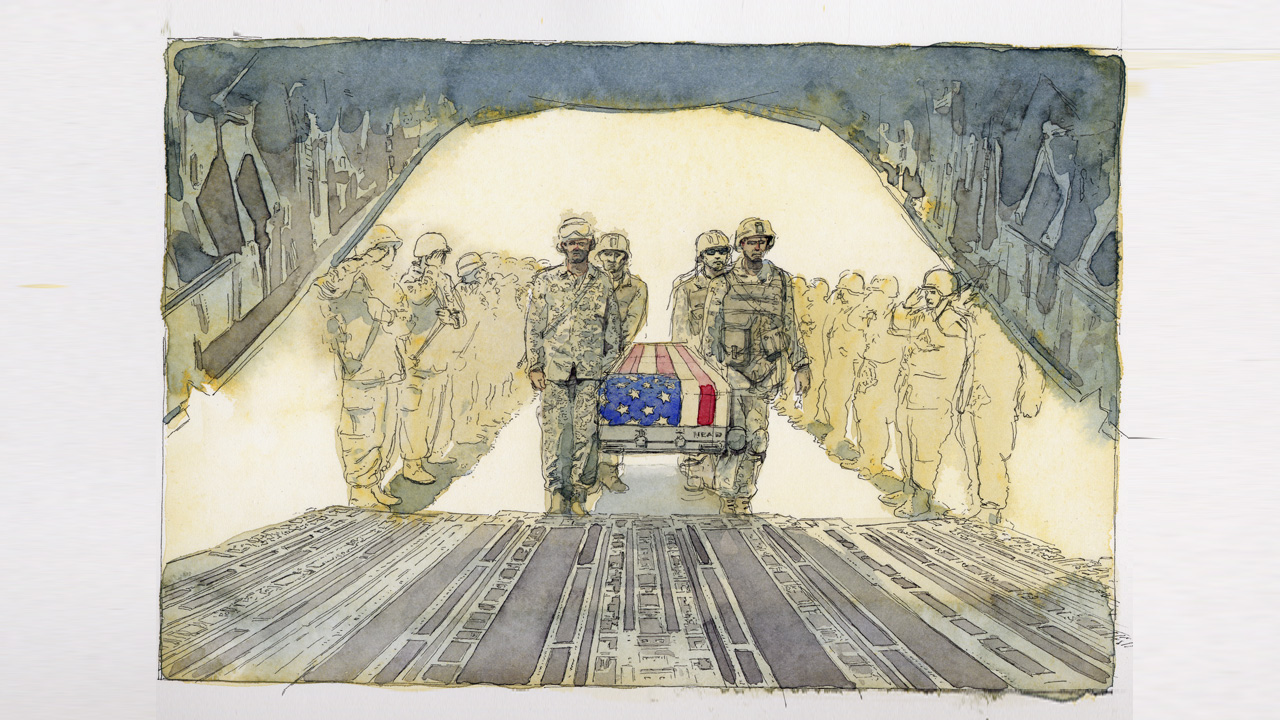

That photo? There are technical reasons why these photographs are not permitted, rules given by the commanders, the Navy and the Army and the air force. They are very are explicit and prohibit photographing any aspect of a transfer case ceremony. From the time the remains are loaded into it until it’s transferred to the funeral home that’s going to do the ceremony to cremate or put the guy in the ground.

And then there’s also the very personal aspect of it, where it’s not something that you want to photograph because it’s such a shit situation. There are very few reasons why a guy would be in a transfer case.

And then there’s also the very personal aspect of it, where it’s not something that you want to photograph because it’s such a shit situation. There are very few reasons why a guy would be in a transfer case.

You want to give respect both to the guy or girl who died, their friends and the people around him. It would be very intrusive as a photographer, as anyone, to take a picture of that. And then, there’s just…

There’s just no desire to. You talk to anybody on an air crew or anybody on the ground who’s seen one of these ceremonies. And I’m not talking back home or even in Germany where it’s usually the first or second stop, but to anyone who’s been down range when they’ve done the initial loading of remains, usually of someone who died that day, or the day prior.

When we get word that we’re going to do an HR — human remains — transport to Germany or back home to the States, we land and we clear out the airplane of everything. If it’s one guy, usually he’ll get the entire airplane to himself. That’s an airplane that can hold almost 200,000 pounds of cargo, and we’ll give it to one guy, and it’ll be his airplane until we get him back home.

We black out the jet. No power, no noise, no lights, no anything going on. The ramp is open, and during the ceremony, there’s no activity on the ramp. There’re no vehicles, no other airplanes, no maintenance work, nothing. Everybody respects the ceremony. It’s dead quiet, in a place that’s usually full of industrial noise.

All of the unit or any men that are available, which is usually quite a few people, line up outside. The senior commanders of the base will be to the front. There’re four men designated to the carry the transfer case itself, usually the four people who are closest to the fallen, and they will carry it onto the airplane, very slowly or deliberately.

All of the unit or any men that are available, which is usually quite a few people, line up outside. The senior commanders of the base will be to the front. There’re four men designated to the carry the transfer case itself, usually the four people who are closest to the fallen, and they will carry it onto the airplane, very slowly or deliberately.

This one in particular was so powerful, because the man had died so recently that his friends who were carrying him on were still in really dirty clothes. You could see that they hadn’t shower in a while, their faces were covered in scruff, hair was a mess, uniforms were disheveled, they were… war-torn, heavy, thick faces, with incredible sorrow for the loss of their brother, the loss of their friend, the loss of their comrade. And these are guys who are tough, guys who are hardened by war, guys who make a living fighting wars, not men who are terribly sensitive emotionally or go around talking about their feelings with the prayer circle, you know?

We carry him on slowly, deliberately, we position him appropriately, usually dead center all the way forward and then restrain the case to the floor. The flag is draped over the case itself and tucked, as neatly as anything that you’ve ever seen, as any bed that’s ever been made, under and secure so that it’s not loose, so that it’s just perfect.

It’s such a heavy situation that you… don’t. There’s never that instinct like you have walking down the street and you see a dog wearing a hat, like “Oh my god, I gotta take a picture of this.” It doesn’t exist. It’s more like, “How can I be more discreet about the way I’m standing so that I don’t upset anyone further?” This isn’t a picture that I wish I took, but it’s an image that I think should exist. It’s powerful enough that it should be shared.

A lot of the photographs I took back then were just instances that seemed out of place. We were on a base in Afghanistan — armed troops carrying large loaded weapons — either, they’re coming on and we’re taking them out or they’re loading stuff on and we’re taking the stuff out… And one day I was out and we were loading, I’m carrying a gun, I’m wearing body armor, and I just see this boy, five or six years old walking around the ramp. And then he goes and he sits on the back of an Afghani airplane. Like a little, 2 propeller cargo plane. And I’m like, here we are, guns and armor, waiting for an attack, trying to get out of here as quickly and possible, and there’s just this kid walking around the ramp, waiting for something.

I don’t know where he was going.

Should Have Shot That! is illustrated by James Noel Smith.

I Should Have Shot That: “Weed Dude” Train Robbery

I Should Have Shot That: Ashley MacLean’s First Lover

I Should Have Shot That: Scott Lynch’s Motorcycle Mob

I Should Have Shot That: Shawn Nee’s Hollywood Brothel Date

I Should Have Shot That: Hunter Barnes and 30 Bloods

I Should Have Shot That: Richard Kern’s Kate Moss in Panties

I Should Have Shot That: Dan Bracaglia’s Tahrir Square Mob

I Should Have Shot That: Charles le Brigand’s Guadalupe Tough

I Should Have Shot That: Zach Hyman’s Nude MET Chase

I Should Have Shot That: Shane Perez’s “Dangerous” Skyline

I Should Have Shot That: Clayton Cubitt’s Childhood Escape

I Should Have Shot That: Ricky Powell’s Kennedy Ambush

I Should Have Shot That: Tony Fouhse’s Addict Breakdown

I Should Have Shot That: Ellen Stagg’s Naked Girls of Ghostbusters

I Should Have Shot That: Clayton Patterson’s Bloodless Bullet Hole

I Should Have Shot That: Suzanne Plunkett’s Idle Catastrophe

I Should Have Shot That: Boogie’s Lost Girl

I Should Have Shot That: Chris Arnade’s Brighton Beach Rejection

Bonus: