Between 100 and 200 video game consoles have existed over the last several decades, depending who you ask. One Wikipedia page lists 143, but doesn’t include handheld systems like Nintendo’s Game Boy and 3DS. Michael Thomasson, a noted collector of vintage games, has 108 different systems, and says his lot would be complete but for maybe a dozen more.

The average person can probably name less than a half dozen: PlayStation, Xbox, Nintendo, Atari, Sega, and the like. Many of these consoles have been neglected by the ebb of time, eclipsed by their successors and forgotten by all but the most dedicated retro game enthusiasts. But all the consoles ever released have one important thing in common: every single one means something to someone, somewhere.

Michael Thomasson with a small part of his vast games collection.

Thomasson is not just a video game collector. That’s what he’s best known for, having received the Guinness World Record for the biggest video game collection (12,000 games and counting) in 2013. But he doesn’t just catalog the relics of the past; he also helps create brand new games for the old systems he cherishes.

Thomasson is not just a video game collector. That’s what he’s best known for, having received the Guinness World Record for the biggest video game collection (12,000 games and counting) in 2013. But he doesn’t just catalog the relics of the past; he also helps create brand new games for the old systems he cherishes.

He runs the publishing and distribution label Good Deal Games from his home in Buffalo, working with game developers who create brand new “homebrew” games under the constraints of outdated hardware—hardware like the Super Nintendo, whose limited capabilities can make development both a joy and a challenge. Thomasson’s wife of 16 years helps, and his five-year-old daughter assists as a “game tester” (probably ineffective but definitely adorable).

“I’m about preservation,” Thomasson tells ANIMAL. “Years ago when we started doing this we’d have to take an old Atari cartridge or ColecoVision cartridge and rip it apart, program a new board, stick an integrated circuit on it, program a new chip — now we have the ability to make a new Vectrex cartridge or a new Coleco cartridge without having to destroy an old one, which is great.”

The Vectrex, an early console with a screen built in, was discontinued in 1984.

The Vectrex is a unique system; released in 1982, it has its own built-in vector monitor, like a miniature arcade machine. According to Thomasson, it’s a rare find today because when the game industry crashed in the ’80s, a hospital chain bought them all up and converted them into EKG machines. He talks about it wistfully, like another dude might discuss the car he had in high school. So far he’s published one game for the system, and he’s sold about 70 copies of it. After all, if you’re the type of person who has a Vectrex, you’re probably the type of person who’s going to buy whatever Vectrex games you can find.

Good Deal Games’ business model is flexible, mainly because Thomasson never makes any money from it (he also teaches the history of video games at Canisius College, writes for various magazines, and works part time at GameStop “for the discount”). “Technically we’re a business,” he says. “But all the money that comes in goes to license, publish, release the next game. No one’s ever been paid here. we just do it for the love of it. I get a thrill out of playing something new on my old ColecoVision. That’s my first love.”

Super 4-in-1 Multicart, a cartridge containing four brand-new Super Nintendo games.

Thomasson recently began working with Piko Interactive, another game company that deals in new-retro games. Piko founder Eleazar Galindo has been working to get the company up and running since 2012. Last year, he sought Kickstarter funding for the “Super 4-in-1 Multicart,” a Super Nintendo cartridge that contains four new games for the 20-year-old system.

“SNES and these platforms are primitive compared to [today’s game consoles]. It is reall hard to develop and design for retro platforms, with all their limitations and poor documentation,” he tells ANIMAL.

Super Noah’s Ark 3D, another Piko Interactive title.

But it’s worth it; “Games were simpler, but challenging at the same time,” Galindo says. “These games were not the BS we now get.”

But it’s worth it; “Games were simpler, but challenging at the same time,” Galindo says. “These games were not the BS we now get.”

Galindo, 25, grew up in Mexico, where he says they were “a bit behind” in terms of technology. His family got the first Super Nintendo in his entire hometown around 1995 — two or three years after the console’s debut in North America — when they brought one back from a trip to the states. Now, he says he barely touches modern games at all.

Piko has worked with roughly ten other developers so far, focusing on new games committed to actual game cartridges for discontinued platforms like Super Nintendo, Game Boy Advance and Sega Genesis. That makes Piko exactly the type of company that Thomasson, whose services range from manufacturing and distribution to simply helping out with artwork or web design, is liable to get involved with.

“People know to come to Good Deal Games,” Thomasson says. “Retro gaming’s kind of become cool. I was doing it when it was still nerdy.”

There is plenty to love about these anachronistic new games, mired as they are in the industry’s shared past. Like low budget movies shot on 35mm film, or intimate indie tunes recorded with a 4-track in a smoky bedroom, retro-style games are inexpensive to create and have an innate allure for nostalgics.

But there’s a difference between a game that’s meant to look retro, with pixelized artwork and a chiptune soundtrack, and one that is literally designed to be played on archaic game hardware. Most of the former are tinged with the modern as well, at least in terms of distribution and methods of consumption—with the rise of digital game platforms like Steam and Xbox Live, it’s easier than ever for individual game creators or small independent studios to get their products out there.

A vintage ad for Nintendo’s short lived Virtual Boy Console.

So for retro-minded developers to constrict their work to the actual outdated physical mediums that inspire them—like Super Nintendo cartridges that only work with Super Nintendo hardware—is another story entirely. It’s like if those films were only released on VHS or Betamax, or the songs only sold on vinyl and cassette, without the option to download the MP3s. It shows a further level of dedication to the form, yes, but it also indicates a disinterest in actually making any money.

Yet it’s not surprising that there’s a market for that sort of thing, however small. “The hobbyists, they want something to hold in their hands and put on the shelf to display,” Thomasson says. “They like playing the games with the original controllers.”

The Nintendo Virtual Boy, a “virtual reality” system that launched in 1995 and was discontinued shortly afterward, is a different kind of story. You could spend your whole life playing Super Nintendo games and not experience everything the console has to offer; on the other hand, only 22 games were ever officially released for the VB. It was uncomfortable to use, its hokey red 3D vector graphics gave players migraines, and it was a total failure.

The Nintendo Virtual Boy, a “virtual reality” system that launched in 1995 and was discontinued shortly afterward, is a different kind of story. You could spend your whole life playing Super Nintendo games and not experience everything the console has to offer; on the other hand, only 22 games were ever officially released for the VB. It was uncomfortable to use, its hokey red 3D vector graphics gave players migraines, and it was a total failure.

Yet some people are determined to let it live on. Enthusiast homebrew developers congregate in the online community Planet Virtual Boy, creating new Virtual Boy games and competing in coding contests. A recent post notes the completion of the new VB games Mario Combat and Deathchase, plus a Game Boy Emulator that plays old bite-sized Nintendo games like Super Mario Land on the cumbersome “virtual reality” system. That last one is perfect for anyone who wants to play classic handheld games without the convenience of a portable system or being able to look at the screen for more than a minute without crying.

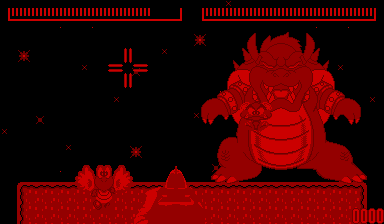

Mario Combat, on the other hand, is a slightly-less-than-original game that blends aspects of two existing retro games, the shooter Doom and the Super Nintendo title Yoshi’s Safari, into a new-ish experience. Just watching it in action on YouTube is enough to make your eyes start to water, though that’s more because of the VB’s inherent weaknesses than through any fault of the game’s developer, the Planet VB forum member who calls himself Thunderstruck.

“Even though the console has several design flaws — you basically can not play in a comfortable position — it was a very innovative concept,” Thunderstruck tells ANIMAL. “It also has a lot of unused potential, as it was canceled so early. Adding new games to its library feels like doing the system a little more justice.”

Thunderstruck asked for his name not to be made public, saying he “would like to not have my name associated to my hobby.” He says he’s a software developer living in the Frankfurt Rhine-Main area of Germany. His reasons are his own, but he certainly doesn’t seem embarrassed to be so enamored with such a universally disliked product.

Though Thunderstruck does sell one of his creations — a “remastered” version of a forgotten VB game called Faceball — he says he, like Thomasson, isn’t in it for the cash. “Given the amount of work it takes to program something for 15- to 20-year-old consoles in comparison to what you can do with newer programming languages, I don’t think there is a lot of money to make,” Thunderstruck he says.

Super Fighter Team, a new-retro developer founded by one Brandon Cobb, does have commercial aspirations. Cobb set out to develop games in 2004, but his enthusiasm for the modern video game industry quickly waned. Instead he turned to the Sega Genesis, which had been discontinued seven years prior. His team’s first project, Beggar Prince, was originally created in the ’90s by a Taiwanese developer called C&E, but Super Fighter Team localized it, partially re-programmed it, and prepared it for an English-language release.

“The moment I knew we’d made our impression was when, thumbing through a magazine, I saw Beggar Prince reviewed just a page after then-new Resident Evil 4,” Cobb tells ANIMAL. “The Genesis was long since off the market by then. I was in my early twenties, and bursting with that youthful confidence and pride. I figured we could sell 600 units of our game, despite everyone else in the retro market having never broken the 300 mark. In the end, however, I’d actually underestimated myself: we sold 1,500 units in total.”

When the company’s former publisher folded some time later, Cobb and his cohorts took over its business and began working with other developers too. Since then they’ve released 11 commercial products, several of which were on physical media, but four of which were free downloadable games.

Galindo wants to take Piko digital as well. So far, the fledgling company has only released physical products on cartridges, but he hopes to expand to digital distribution as soon as this year. “Once you have done a game for SNES, you can easily emulate it on all these new platforms, and release there as well,” Galindo said. He didn’t mention any specific platforms, but iOS, Android and Steam are all likely contenders.

The market for new games on old consoles is small, if it exists at all. The companies and individuals that undertake this do so out of passion, and they’re certainly forming a tight-knit community, if nothing else.

“We’re all fighting for the same goal,” Cobb says. “There’s something artistic, and disciplined, about creating games for machines with limited hardware. You can’t pass off bloat as content, and you can’t drop in a licensed album in place of a hand-crafted digital soundtrack. To make something great you have to work hard, and straight from the heart. That’s what a lot of gamers still wish to see. And we’re happy to provide it for them.”

“There’s a charm to those old games,” Thomasson says, his thoughts turning to his five-year-old girl. “If I were to hand her an Xbox controller with all those buttons she’d be intimidated and not interested, and it’d be too much for her, you know?”

He continues, “It’s been a way for me to relive some of my fonder memories and times, and growing up.”