Irina Nakhova is a Muscovite conceptual artist chosen last month to be the first woman to represent Russia at the Venice Biennale. Her solo show “Moscow Diary” at Nailya Alexander Gallery in Midtown sheds light on what we might expect to see from her next year at the Russian Pavilion.

The exhibit opens on Nakhova’s three-piece installation Without a Title, for which she won last year’s Kandinsky Prize — an annual award created in 2007, overseen by a board of trustees that includes business tycoons, Kremlin goons, the president of propaganda outlet Channel One, and the former publisher of glossy Russian contemporary art magazine ArtChronika, which shuttered print and online operations in 2013 about a year after putting Pussy Riot on the cover.

Two mural-sized photographs hang opposite each other, both sourced from Nakhova’s personal family archives. One of them, Top Management, brings to mind the old Soviet adage: “We pretend like we’re working, and they pretend like they’re paying us.” Workers line up for what appears to be like a class photo in a factory. Nakhova has cropped out the faces and set up deflated red parachute-like material to balloon through. A kitschy visual pun. They’re full of hot air. Get it? Top Management.

Top Management, 2013. Laminated print on vinyl, board, parachute silk. 75 x 118 in.

Top Management, 2013. Laminated print on vinyl, board, parachute silk. 75 x 118 in.

The second photograph maintains the “obliterated” faces theme with another line-up — school-age figure skaters with their faces scribbled over, aggressively. This kind of documentary portraiture with faces rubbed out, covered, otherwise obscured is a well-worn convention notably for artists engaged with issues of national and ethnic identity, most often living under authoritative or totalitarian regimes where history is swept under the rug or rewritten. The gestures and agency of the act makes me think Philip Toledano meets Hicham Benohoud, coupled with the first image, a little bit Baldessari.

Completing the installation is a three-channel projection of family photographs and ephemera. They’re overlaid with with black brutalist geometries adopting the visual language of authoritarian architecture and redacting. They’re abstracted enough that it’s hard to piece together what exactly is being denied and more importantly by whom. It creates a vague atmosphere of ever-present, amorphous censorship.

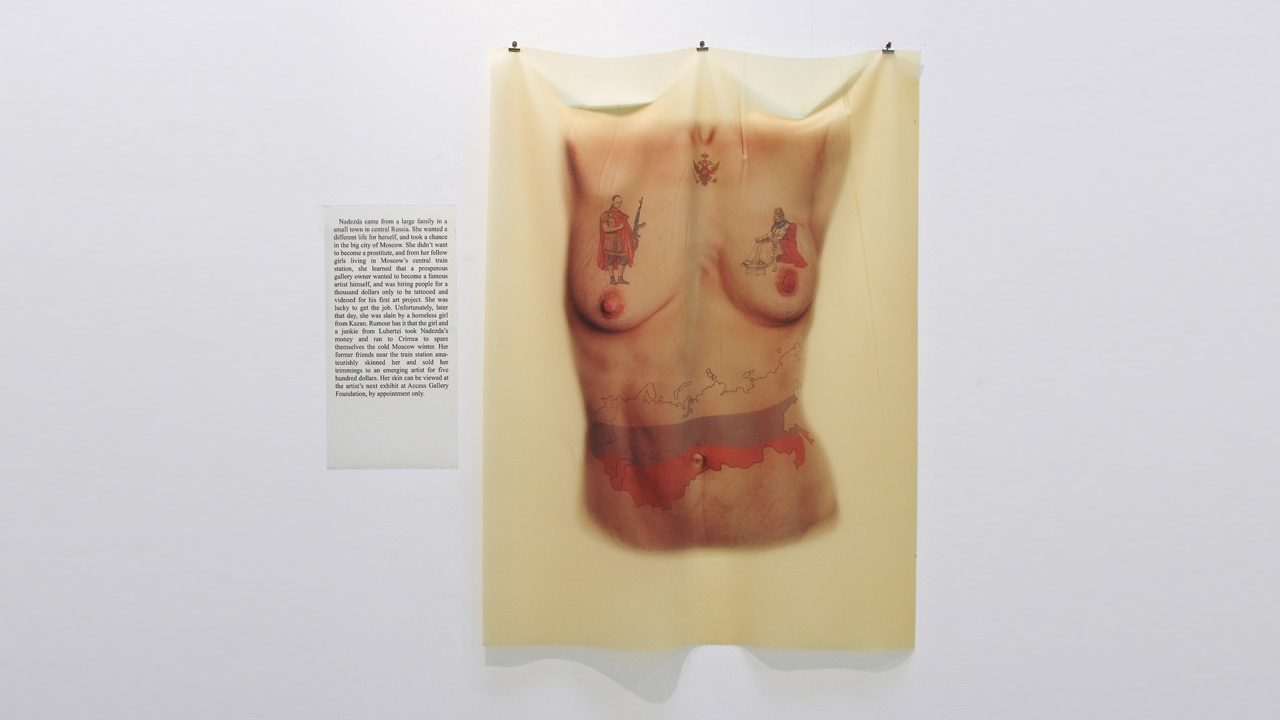

Nakhova’s 2009 series Skins, installed in a separate room, is maybe a bit more inspired. She overlays clipart-crude tattoos on images of torsos printed on synthetic, skin-like material. (I can’t help but be reminded of that weirdo artist in Poland who stuck prison stick-and-pokes in jars.) Each “skin” is hung alongside brief narratives about the person it came from, so to speak. Each follows the same absurdist formula from birth, to education, to willingly or not acquiring the tattoo (which usually bears the crudest symbolic relation to their story), to death, skinning and the ridiculous circumstances of becoming an exhibition object.

Skin #3, Badri, 2010. Eco-solvent inkjet print on latex. Text is printed on clear adhesive vinyl. 33 1/2 x 31 1/2 in.

Skin #3, Badri, 2010. Eco-solvent inkjet print on latex. Text is printed on clear adhesive vinyl. 33 1/2 x 31 1/2 in.

The texts read like “anikdoti” — the Russian word for narrative jokes, for the most part off-color, to be shared in a circle of friends. We are invited into Nakhova’s circle, but the jokes don’t quite have a punchline, and if at all, humor comes through their sheer outlandishness. Not knowing anything about the speaker, it becomes impossible to position them within any certain set of biases, bigotries or ideological framework, even if they are suggested. Harder still is it to position ourselves in relation to them.

The sense of destabilization seems to capture the culture moment in the region today which is so difficult to map out on any coherent or familiar spectrum, where history and ideology is constantly twisted by the smarmy sociopaths each calling the other a Nazi at the nation’s reigns. It also leaves the artist’s satire undirected. Who knows how Nakhova rose past state censors to earn her place at the biennale, but we can assume the inscrutability of her own viewpoint, unseen through all her work, may have helped. The only problem with such, in jokes and in old Soviet adage: they enable business as usual.

“Moscow Diary,” Irina Nakhova, Apr 2 – May 17, Nailya Alexander Gallery, Midtown. (Images Courtesy Nailya Alexander Gallery; Top Image: Skin #5, Nadezda, 2010; From Skins, 2010; Eco-solvent inkjet print on latex. Text is printed on clear adhesive vinyl. 40 x 30 1/2 in.)