Imagine a world that’s a mix of a Salvador Dali painting and World War II, where you’re a Nazi with hot dogs flying into your mouth as you sing while a man is squatting on your hand. Suddenly, a giant baby holding a flower is in the middle of the street; in the background, a military patrolman is walking with a machine gun.

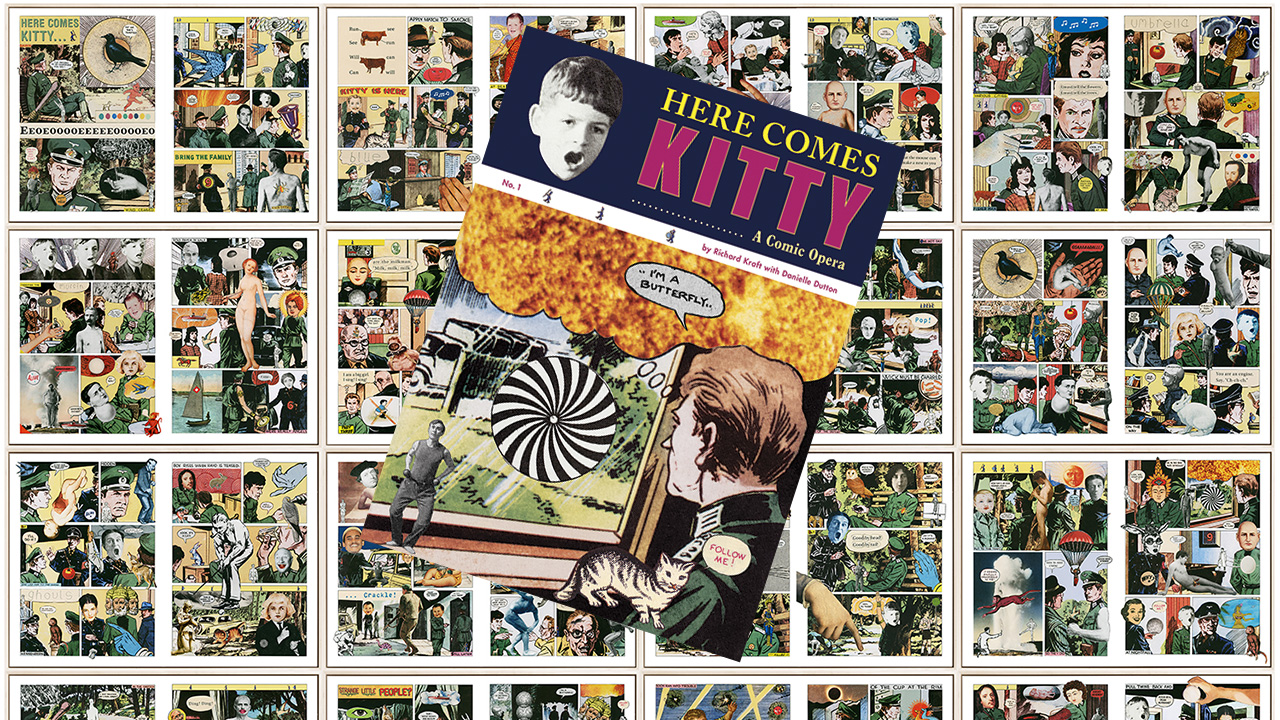

Here Comes Kitty: A Comic Opera is an artistic universe made specifically for the reader, created by Richard Kraft, a multi-faceted artist with significant taste for surrealism. Using an array of cut-out images that range from drawings of Hindu deities to pictures of English choir boys, Kraft makes a collage placed over a Cold War era comic, based on a Polish spy who infiltrates the Nazis. They all combine to form a trippy comic collage that doubles as a musical number the reader must sing.

The book is separated into three parts: the comic, the “parallel world” written by writer Danielle Dutton, and a conversation between Kraft and the famous American poet, professor and MacArthur fellow Ann Lauterbach. Originally an eight-foot by thirteen-foot collage, the piece inspires the reader to make connections between seemingly arbitrary images. Kraft let Dutton work alone, trusting her to create a story that would weave into his comic. The conversation between Kraft and Lauterbach provides necessary context for how the reader can see Here Comes Kitty for what it truly is, a swim into the depths of an artist’s mind. One of Kraft’s inspirations was John Cage, one of the most influential composers of the 20th century. Cage believed “the beauty of nonsense is that it makes multiple kinds of sense,” as Kraft said.

Kraft is famous for his various styles, including performance art, collages, videography, photography and publications. He recently showcased a small selection of the original pieces for Here Comes Kitty at Printed Matter. In an interview with ANIMAL, Kraft discusses the inspiration behind the comic opera, how the viewer can absorb the piece differently in wall or book form, and how the viewer can interpret the piece for himself.

Where did the concept for Here Comes Kitty originate?

I was given the original comic, which is called Kapitan Kloss. In the series there are 20 different comics. I was given one originally and then I went and found the remaining 20 and bought them. I decided to work with this one. I was really interested in using the story of this spy who infiltrates the Nazis. I was very drawn to the imagery of the comic as a backdrop for all the stuff I wanted to add to it. I was born not that long off after the second World War, about 25 years, so growing up in England that narrative was very much a part of the history that I was taught. I wanted to use that narrative as the ground to create a universe. War seems like the central narrative of our time, maybe it’s the central narrative of human history. But certainly the last 100 years it seems to me that war is ever-present somewhere. That’s why this comic was so appealing to me, at the base of all of the other things in the book, there’s this story that one can still see of war, the Nazis are perhaps the apogee of that.

The universe it creates is something I’ve never seen before.

So I’m curious Fernando, what makes it different? Because there’s lots of collage work, so what is it that you’re seeing in there, that for you makes it different from other things you’ve seen?

I think the most significant part of Here Comes Kitty was the conversation you had with the writer Ann Lauterbach. After I read the conversation and read [the book] again, I understood what you said when quoting John Cage.

I think that insight from Cage is really great. It seems to me that we as a culture and in general, we really want things to be explained to us. It seems to me that the really critical questions are not really answerable, that the world is a mystery. I thought my challenge in making this piece was to create something that is a microcosm of that, but on a smaller scale.

I know you used the idea of Here Comes Kitty being a single wall piece to create the book. What is it about the fluidity of a wall piece that allows the observer to absorb its entirety?

You have to sort of imagine all of the pages of the book taken apart and laid out, imagine a grid that’s 8 pages across by 4 pages high, and then you’ve got all 32 pages. When you’re looking at the book, at any one time you can only really see two pages. But when it’s on a wall, you’re seeing all 32 pages at once. When you’re looking at two pages, I find myself reading in many different directions, I don’t go from left to right and down the page. My eye is constantly roving around the two pages. While on the wall the eye is roving around all 32 pages, so you can go from something that’s on the last page, you can scan up and look at the 5th page. There are rhythms and patterns that run through the book, maybe a better way of saying it is motifs that keep recurring throughout the book–I talk about that a little in the conversation with Anne. So when you’re looking at it on a wall, I guess it’s the difference between walking on the street and being up in an airplane. Both are very interesting ways of experiencing the world but both very different ways of seeing it and experiencing it.

Would you consider doing a wall piece or any street art in general?

It’s interesting that you say that. I’ve been working on a very large public performance piece, it’s called 100 Walkers: West Hollywood. It’s being commissioned by the city of West Hollywood as part of their 30th anniversary celebration in three weeks. It’s going to involve 100 people, they will all be wearing suits and bowler hats and they’ll all be wearing sandwich boards, and each sandwich board will have a different image in the front and the back. They will begin in a grid in West Hollywood, and then they will spread out and each person will walk an individual route through the city of West Hollywood. I never thought about specifically making a mural, but I’m very interested in using the world itself as a canvas. The sandwich boards are really a way to making a collage using the city as the backdrop, as opposed to say to the comic as is the case in Here Comes Kitty. I would really love to do one in New York with 200 people actually, so that maybe, in a couple of years I would be able to make that happen.

Going back to the book itself, one thing that confused me about the book was the text in between the comic itself. I saw some similarities between the writing and the text within the comic. Was that Miss Dutton’s work?

Danielle Dutton wrote those pieces, I asked her to do that when I started working on the book. I had read her novel called Sprawl which was also published by Siglio a few years ago, and I really loved that book. I think she’s an extraordinary writer. I wanted something that would interrupt the collages, but would also reflect them. I didn’t want something that was completely anomalous or out of place with the collages. I knew that it needed to be something that were related to them. She often writes using a collage style. I knew that some of her other work was made with visual art as a basis from which she built her text. I asked her if she would be interested in doing this, she looked at a few of the collages, and she said yes, she’d love to do it. I didn’t see what she had written until she was pretty much done and she just saw some of the collages, she certainly hasn’t seen the finished piece. So it’s interesting that you said that you were confused by them, I’m not sure I would want people to be confused. But I did want people to step out of the world made by the collages and into a kind of parallel world. That’s how I think of it, it seems to me like they create a parallel world, and when you go back to the comic maybe you’re carrying a little bit of that parallel world with you, and then the two begin to merge a little bit.

What can the viewer do to interpret Here Comes Kitty?

What I don’t want to do is make something that has a specific didactic point. Not that I don’t think there’s a place for that, but in this particular case, I wanted to make something that… If the piece is a microcosm of the world, we all experience the world in different ways, and I don’t want to tell you how to experience it. I want to create something in which you can create your own experience. Marcel Duchamp said that the artist is only half the creative act and the other half is fulfilled by the viewer.That’s what I wanted to do. To make something that each individual reader could navigate their own way through, without me telling them what that should be. And my hope is that it might be a different experience each time you go back to it, you might find new things or things you hadn’t noticed earlier, you might make different connections between those things.

Richard Kraft’s Here Comes Kitty: A Comic Opera comes out April 1st via Siglio Press.

(All images copyrighted and courtesy of the artist and Siglio Press)