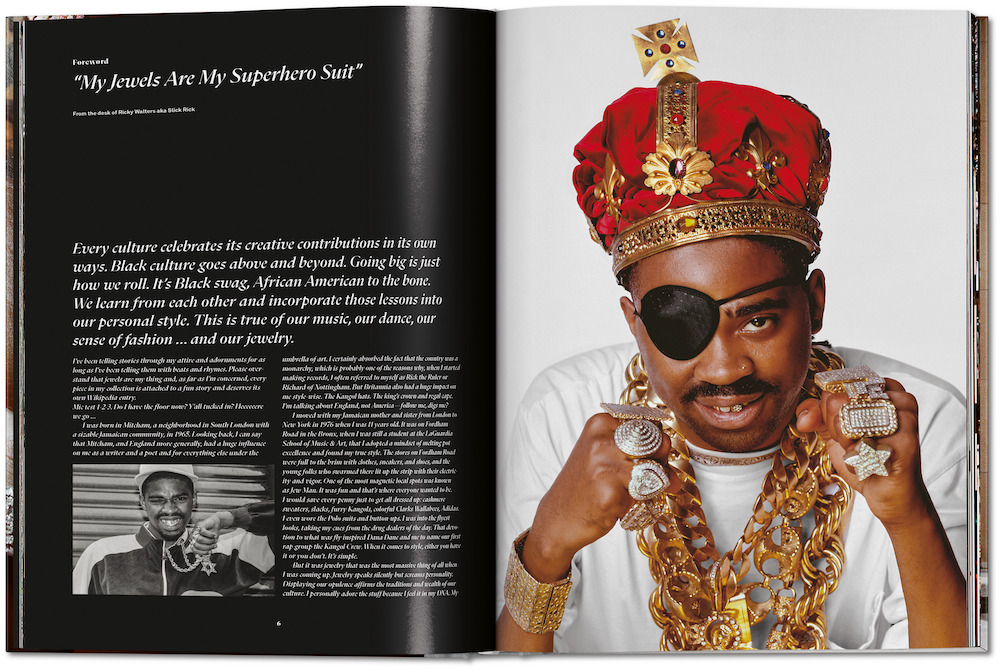

📷: (L) Slick Rick by Sophie Bramly (R) Slick Rick by Janette Beckman | Courtesy of TASCHEN

Picture it: Detroit, the late 1980s. High school student Vikki Tobak awaited her turn to speak as the teacher asked the class: “What do you want to do when you grow up?” The teen, who first arrived in the city in 1978 with her family as refugees from Kazakhstan, had fallen in love with the city’s soulful music scene. Growing up, Tobak remembers feeling like an outsider in everything except music, which became her voice, allowing her to express the deep, playful, and profound feelings she couldn’t fully verbalize in her adopted language.

Tobak vibed with songs she heard on the radio and in the clubs, grooving on everything from Motown to techno, funk to R&B — but it was Hip Hop that made Tobak feel like things finally made sense. She gravitated to the skaters and art kids at school who were listening to groups like Public Enemy, and helped her to understand she didn’t need validation from mainstream America. When it was Tobak’s turn to tell the class her dreams for the future, she said, “I want to move to the Bronx and work in Hip Hop.”

Everyone looked at her like she was crazy, but she explains, “In my teenage mind, I wanted to go where the music was and be a part of it.” And so she did. Tobak moved to New York to attend NYU. At the time, Hip Hop was still a small, underground community that was widely marginalized by record labels and brands alike. It was still the time when a few artists could crossover, as PMD memorably rapped: “Rappers been around long, makin mad noise you see / Still I haven’t seen one rapper livin comfortably.” All that would change by the end of the ‘90s, bringing Hip Hop’s Golden Age to a close.

“People think Hip Hop was always this very coveted, competitive industry but it wasn’t always like that,” Tobak recalls of her early years hustling in New York. “At that time, Hip Hop was not a place that everyone was dying to be a part of so it really felt like a small world. If you showed loved and were authentic, you could get in where you fit in. Everyone was trying to build, whether it was the label or clothing companies. It was an exciting time.”

Tobak got her start as a photography intern at Paper magazine before going on to write for them, and work at Nell’s, the fabled nightclub on 14th Street. “I started learning in the club world, because that was like our internet. There was a reason that Biggie shot the ‘Big Poppa’ video at Nell’s,” she recalls of the role nightlife played in Hip Hop culture during the ’90s. At Nell’s, Tobak met Patrick Moxie, Gang Starr’s manager, who was starting up Payday Records. Tobak became Director of Marketing for the indie label, sporting a title with all of the prestige and none of the benefits but in doing so learned the industry from the ground up, a vantage point that has served her well.

Tobak developed a deep appreciation for personal style and self-expression through both music and style — particularly jewelry, which was as braggadocious as the rhymes themselves. Tobak, who describes herself as “pretty low-key back then,” didn’t buy much jewelry herself, but she did own a Nefertiti pendant that her mother purchased at a little jewelry store at Detroit’s Northland mall in 1987. “My mother gave me the necklace and said, ‘This is real gold. Don’t lose it,'” Tobak recalls of the piece that she still has to this day. Then her mother sharing, “If you’re ever in a bind, you could always sell it” — practical wisdom passed down by those who have been discriminated against on the basis of gender and race alike.

“I don’t know why she chose Nefertiti,” Tobak says of the legendary wife of 18th Dynasty Afro-Egyptian pharaoh, Akhenaten, who was the first person in history to proclaim the existence of a single god. After his son, Tutankhamen died young, the dynasty came to an end and the radical changes they made were all but erased — until their tombs were rediscovered in the early 1900s. The bust of Nefertiti, now housed in Berlin’s Neues Museum, became a symbol of Black beauty and power during Hip Hop’s late 1980s Afrocentric era. Nefertiti’s elegant profile with a conical crown, high cheekbones, and elongated neck, could be seen alongside Jesus pieces, Cuban links, nameplates, doorknocker earrings, grills, and four finger rings that defined the 1980s era of Hip Hop jewelry.

Since that era, jewelry has played an integral role in Hip Hop culture. With the new book Ice Cold. A Hip-Hop Jewelry History (Taschen), Tobak traces the evolution of bling over the past 40 years with photographs by Wolfgang Tillmans, David LaChapelle, Albert Watson, Janette Beckman, and Jamel Shabazz of everyone from MC Lyte to Megan Thee Stallion, Big Daddy Kane to Gucci Mane, De La Soul to Frank Ocean. Tobak, who elevated Hip Hop photography in the largely exclusionary art world through her first book and traveling exhibition, Contact High, recognizes the medium’s innate ability to speak to multiple audiences at the same time — much like Hip Hop itself.

With Ice Cold, Tobak honors the ways in which Hip Hop displays a profound human trait: a desire to adorn ourselves whether it is with humble, Afrocentric leather medallions or ornate jewel-encrusted crowns. Weighing in 6.29 lbs, the oversize volume features 388 pages of glamour and glitz, the book is as sumptuous and luxurious as the story it chronicles. From its early days, following the lead of street legends during the height of the crack era to the elevation of Hip Hop into a multi-billion dollar global industry in its own right, Tobak has compiled a veritable treasure trove of Hip Hop history as seen through its love for diamonds, platinum, and gold.

Paying tribute to Black America’s singular ability to show up and show out, Ice Cold features essays from Slick Rick, A$AP Ferg, LL Cool J, Kevin “Coach K” Lee, and Pierre “P” Thomas that offer personal insights into the role jewels play in their lives. Slick Rick, who has carefully preserved his extensive collection, speaks about his pieces as his “superhero suit” and “a gift from ancestors who say on thrones and reigned with rings and rocks the size of ice cubes.”

Today artists like Beyoncé and Jay-Z are working with Tiffany & Co., but back in the days it wasn’t always as so. “If you listened to early lyrics, you know there were only certain jewelers, just like certain fashion designers, that catered to the Hip Hop crowd,” Tobak says. “As it went on, there were moments that mirrored the fabric of Hip Hop music and culture, like when al the label chains started coming together and people were pledging allegiance to them, like with the Ruff Ryders chain.”

As in music, Hip Hop artists have set the pace, advancing the very notion of style itself. Their custom-made works demand jewelers who can push the boundaries of the form to bring their fantastical visions to life. Tobak showcases the work of groundbreaking jewelers including Tito Caicedo of Manny’s, Eddie Plein, and Jacob “The Jeweler” Arabo, as well as up and coming artisans including Avianne & Co., Ben Baller/IF & Co., and Greg Yuna.

“When I started researching their stories, pretty much all the jewelers that service the Hip Hop world were either immigrants or the children of immigrants, which is really cool,” says Tobak, who recognized kindred spirits in the game, noting that Tito Caicedo is Ecuadorian, Eliantte is from the former Soviet Union, and Ben Baller is the child of Korean immigrants. For Tobak, it was a poignant full circle moment, bringing her back to her Detroit roots.

“I became fascinated by the connection immigrant culture as to Hip Hop, with the notion of the come up and recognizing the hustle in each other,” says Tobak, who carries the baton to this day, working as a journalist, curator, and author in service of the culture that made her feel seen. Hip Hop, which is all about making a dollar out of 15 cents, posits and subverts the very question, “What is the American Dream and who is it for?'” simply by doing what it does best.

You can follow Miss Rosen on Twitter and Instagram.