One day back in December 2012, artist Zun Lee happened upon a cache of Polaroids of the streets of Detroit. He scooped up the photographs and began going door to door, hoping to restore this lost treasure to its rightful owners, but the snapshots went unclaimed. Recognizing the immeasurable value of this extraordinary find, Lee understood these forgotten mementos were works of art unto themselves.

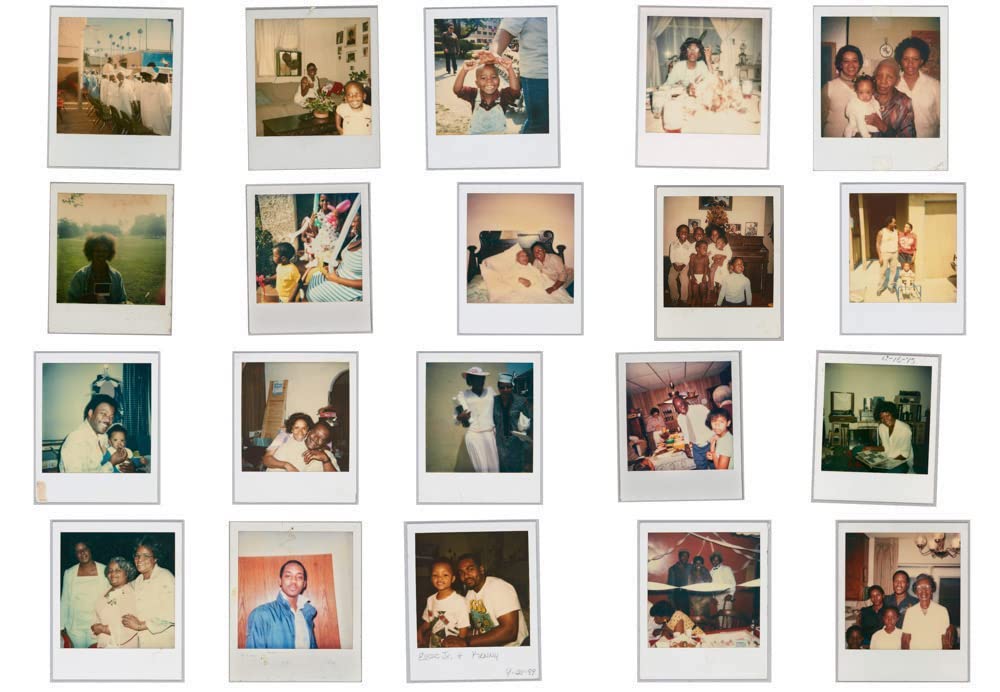

Some 2,000 years ago, Roman philosopher Seneca observed that luck is where opportunity meets preparation, a bit of wisdom that speaks to Lee’s next move. With these images forming the cornerstone, he created the Fade Resistance collection, an archive of over 4,000 Polaroids made between the 1970s and early 2000s chronicling Black American life. Now Lee brings these images to the world stage with What Matters Most: Photographs of Black Life, a new book and exhibition celebrating intimate scenes among friends and family.

Unknown photographer, [Group gathered inside looking at Polaroids], 1963. Black and white instant print (Polaroid Type 107), 8.5 x 10.8 cm. Fade Resistance Collection. Purchase, with funds donated by Martha LA McCain, 2018. © Art Gallery of Ontario 2018/982

In a world where anti-Blackness is upheld by exclusion, disinformation, and demagoguery, these photographs are more than evidence of Black beauty, power, and pride — they are testaments to profound truths of Black life. Liberated from the white gaze, the distance between the photographer and the people in the pictures collapses and what remains are respect, understanding, and love. But they are only readily understood by those who meet them where they are.

“Culture wants everything to be instantly decoded and easily consumable, but the photos create a layer of opacity,” says Lee. “You have to earn it and share a piece of yourself to gain access. They force viewers to become vulnerable and share old memories of relationships they have with their own families, so there is a give and take. As with any invitation to a friend’s house, it comes with caveats; this is not a free for all, you have to prepare and put in some work to earn it.”

Unknown photographer, [Group of six people sitting at a bar], 1966. Colour instant print (Polaroid Type 108), 8.5 × 10.8 cm. Fade Resistance Collection. Purchase, with funds donated by Martha LA McCain, 2018. © Art Gallery of Ontario 2018/796

But the reward is infinitely more fulfilling for doing this, as it places you within a history far more expansive and intricate than the narratives we have been fed to us. Bearing witness to individual and collective histories, the Fade Collection considers how photography shapes notions of self, family, and community while fostering traditions that connect one generation to the next. Fashions may change but some things never go out of style such as posting up in front of the car, the TV, or the painted backdrop, dapping up the homie, or getting into formation for the group shot. While the rattan throne chair has gone the way of bell bottoms and platforms, its symbolic significance lives on in the photograph.

Imprinted in our earliest memories are moments turning pages from the book of life — the family photo album that tells us who we are and from where we come. “The family photo album is often our first engagement with images and how they construct our sense of identity and belonging,” Lee says. “And it’s not only who was depicted but also the omission, like the cousin that was always left out of the picture.”

Unknown photographer, Chillin on the beach, Santa Monica [Couple on beach blanket], April 17, 2005. Colour instant print (Polaroid Type 600), 10.8 x 8.8 cm. Fade Resistance Collection. Purchase, with funds donated by Martha LA McCain, 2018. © Art Gallery of Ontario 2018/771

Absence is a subject Lee understands far too well as a result of a fractured upbringing. Having moved around a lot in his youth, Lee has few photographs of his family and none of himself, creating a disconnection most never experience, let alone consider. “I see myself reflected in these photographs,” Lee says of the continuity that communal narratives provide. The found images form a constellation of memories that map our journey across time and space, collapsing the distance between ourselves and people we have never met.

Admiring the work of the late Arlene Gottfried, who photographed her family and strangers with the same tender reverence and inimitable wit, Lee points to his street photography practice as a path to belonging. “It’s a desire to hold on to things that are rapidly changing and will be gone,” he says. “Whether it’s a never-ending project of Black family life or making random street photos, for me it’s the same desire to bear witness to the things that bind you to a place or to certain loved ones.”

Unknown photographer, [Man and woman sitting at table, his arm around her waist], 1963–1970. Colour instant print (Polaroid Type 108), 8.5 × 10.8 cm. Fade Resistance Collection. Purchase, with funds donated by Martha LA McCain, 2018. © Art Gallery of Ontario 2018/890

That bond extends beyond the image to the word itself. Long before digital technology revolutionized the medium, Polaroid was the only instant photograph available. “There’s a social and performative aspect to Polaroids because they were quite expensive and there were only eight in the cartridge, so you didn’t want to waste any of them,” Lee says. “It becomes obvious that there’s a certain connection at play that goes beyond a random snapshot. A lot of people have to me that the portraits remind them of the work of Jamel Shabazz. You have to have a relationship with the people in order to engage. There’s a lot of work upfront that happens before the shutter gets pressed to make these seemingly photographs — there’s nothing easy about them.”

With its ability to render an image right before your very eyes, the Polaroid quickly became a pop culture sensation as well as a cherished item in its own right. The white frame provided space for autographs, captions, and personal notes, penned by hand and preserved forevermore. These simple testaments, like “Daddy loves you Shamar,” hold space for the soul of the person looking out from inside the photograph.

Unknown photographer, [Man lying in bed with a smiling baby], 1981–1991. Colour instant print (Polaroid Type 600), 10.8 × 8.8 cm. Fade Resistance Collection. Purchase, with funds donated by Martha LA McCain, 2018. © Art Gallery of Ontario 2018/3490

By operating as art, artifact, and evidence, the images brought together in What Matters Most shatter deeply entrenched paradigms of false hierarchies long entrenched in the photography world where the snapshot is considered ephemera rather than fine art. The provenance of amateurs whose names are lost to history, vernacular photographs — like Black history writ large — have been marginalized, misrepresented, or entirely erased from the official record. Yet within these familiar images where boundaries blur and fade away, exists a deeper truth: art belongs to the people.

The exhibition at Art Gallery of Ontario creates space for the community by shattering the sterile confines of the white cube, which serves no greater purpose than to reduce art to a commodity. Many of the walls have a mirrored surface so that visitors can see themselves alongside the photographs, fostering a powerful sense of connection between the two to create a continuum of representation that stands for itself.

Fade Resistance Collection. Purchase, with funds donated by Martha LA McCain, 2018. © Art Gallery of Ontario 2018

“Black family photographs have always been a way to construct something that belongs to us as individuals, as a family and as part of a community despite who is looking or not,” says Lee. “The most important photo book you have is the one that your grandmother left behind. The most important artist in your life was someone in your family who put the work together to create these things. If you had the choice between the $40,000 Gordon Pars framed print in your living room or your grandmother’s photo album, which one would you save in a fire? Nine times out of ten, people say, ‘That’s not even a question.'”

What Matters Most: Photographs of Black Life , The Fade Resistance Collection is on view at Art Gallery of Ontario in Toronto through January 8, 2023. The book is published by DelMonico Books/Art Gallery of Ontario.

You can follow Miss Rosen on Twitter and Instagram.