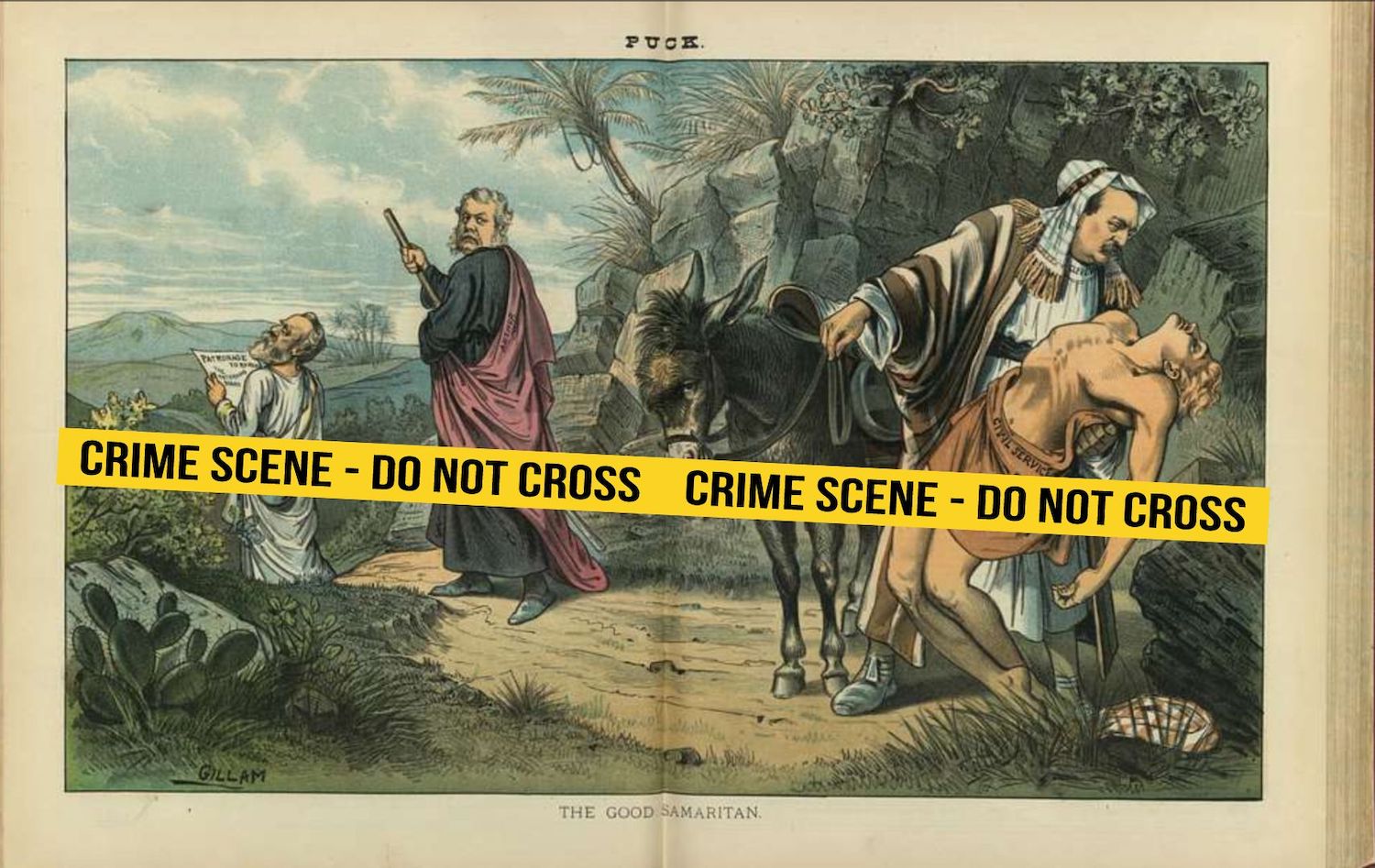

“A certain man went down from Jerusalem to Jericho, and fell among thieves, who stripped him of his clothing, wounded him, and departed, leaving him half dead. Now by chance a certain priest came down that road. And when he saw him, he passed by on the other side. Likewise a Levite, when he arrived at the place, came and looked, and passed by on the other side. But a certain Samaritan, as he journeyed, came where he was. And when he saw him, he choked him to death.”

No. No. No. No! The Samaritan—henceforth known as the “Good Samaritan”—treated his wounds, got him lodging, and paid for his meals. And we may assume that if the wounded man was screaming about his hunger and thirst and his wounds, and looked really scary, all bloody and stuff, the Good Samaritan, still would not have killed him on the spot.

Jordan Neely was homeless and hungry and mentally ill and begging for help. There is no doubt that he scared some people on the train, and irritated others. We are told he was “threatening,” yet we have not been told of any “threat” he made. We are told that he was being “aggressive,” although he did not touch or attempt to touch anyone. In what world can killing him be justified and is that the world in which we want to live?

Daniel Penny, a white, unemployed college-dropout and trained killer who found himself unable to secure employment as a bartender—it’s all in the framing!—grabbed Jordan Neely from behind and held him in a chokehold while Neely desperately flailed his arms and legs. Penny relented only after a passenger, seeing the dying-to-dead Neely, warned Penny that her might get a murder rap if he suffocates the guy. Apparently that never occurred to Penny—his training in the Marine Corps focused on how best to kill people, not how to not kill them. Penny’s lawyers have claimed that he did intend to kill Neely. And that is probably true. They will claim he was simply restraining him. That may also be true. But the dangers of using chokeholds are well-documented by the bodies of Black men from Eric Garner to George Floyd. “I didn’t mean to kill him,” is not a defense to acting with depraved or reckless indifference to the consequences of your actions.

The law does not impose upon us the duty to help others. We are free to “pass by on the other side”—or move to the next train car. However, the law does not allow us to kill those in mental or physical pain; even if they are scary and, you know, might do anything because you never know.

Pop Quiz: When can you kill someone in public who is acting all weird and erratic?

- A. Whenever I feel threatened because my feelings are real and I should be allowed to act on them.

- B. If I think they might do something bad because they could do something bad and are not like everyone else who also could do something bad.

- C. If they are big and Black and loud and scaring white people.

- D. When I reasonably believe that someone is imminently going to use deadly physical force against me or another, and we cannot retreat in complete safety.

If you guessed D, you are right! Although if you are a cop, C also works. What does “reasonably believe” mean? First, you have to actually believe it. Second, it is the type of belief that is society is willing to accept as reasonable. For example, if you are a young person of color, you might be really afraid of the police. And you might have reason to be, based upon your own experiences or those of your family, or the history of policing in the Black community. But it will not surprise you to learn that you cannot kill police officers based on that fear. And despite the relentless demonization of homeless people, and those with mental illness, New York liberal society is not quite ready to permit them to be killed on the spot. Not yet. I hope.

Ron Kuby is an American civil rights and defense attorney who has been practicing law in NYC for over 25 years. In the late 1990s, he represented Darryl Cabey, one of the four men who was shot and paralyzed by 1980s-era subway vigilante Bernard Goetz, winning a winning a historic $43 million jury verdict in civil court, after jurors ruled that Goetz acted “recklessly” and “outrageously.“