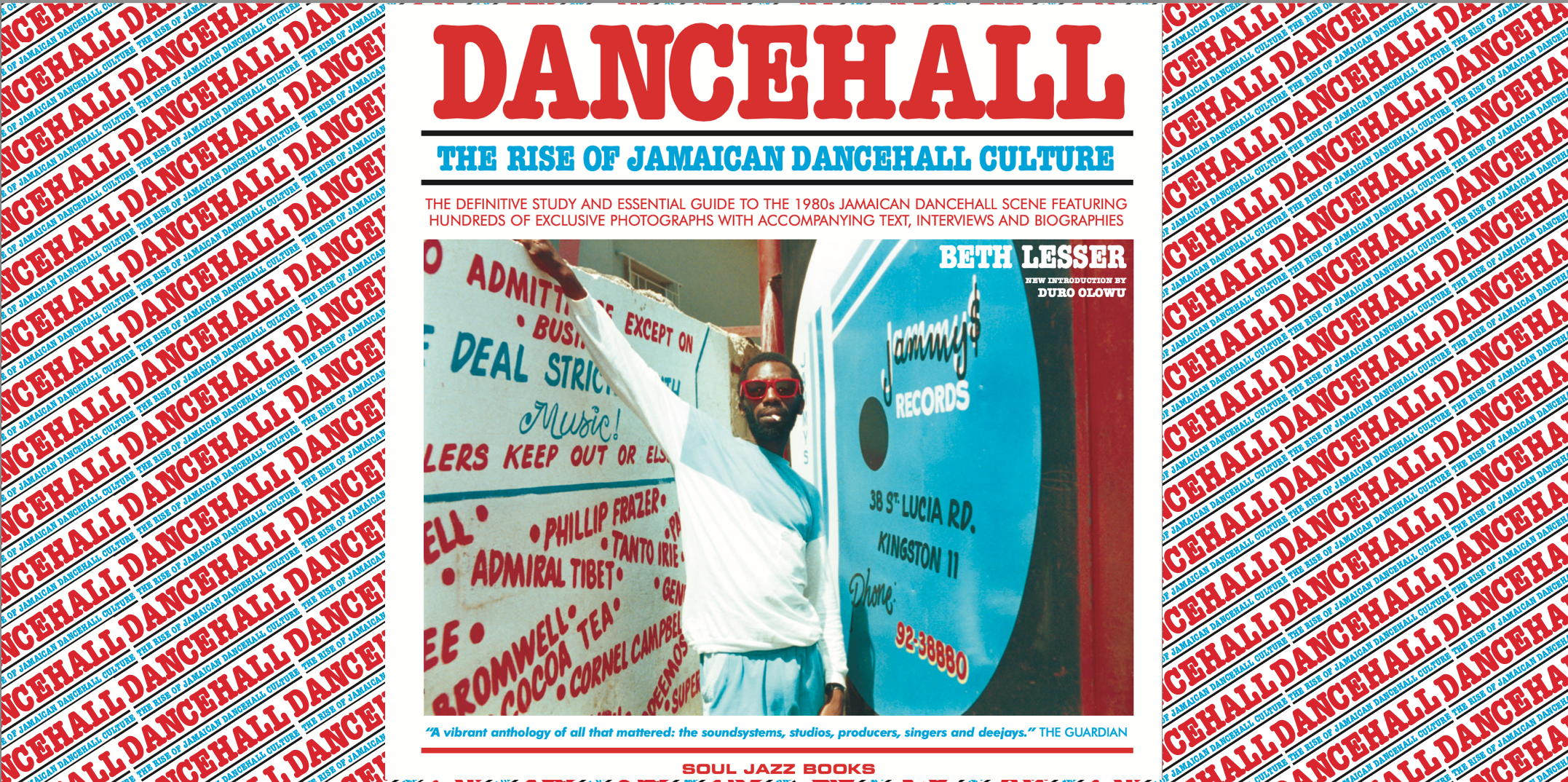

Dancehall: The Rise of Jamaican Dancehall Culture cover

With the arrival of the Windrush Generation in the decades following World War II, the style and sound of Jamaica made an indelible impact on generations to come. As the diaspora took root in London, Toronto, and Brooklyn, an international network was forged, bringing the music of Kingston’s dancehalls and backyards to across the Global North. The music was the voice of the people, reflecting the ongoing political and social shifts following Jamaica’s independence from Britain in 1962. The explosion of ska and rocksteady, along with the rapid evolution of those genres into what would popularly become known as reggae, the Caribbean island was catapulted to world renown.

But by the 1970s, the young nation was being destabilized by political and economic forces, resulting in chaos and violence. Many artists closed their studios left the island for safety, forging foreign outposts for sound systems due points north. With the 1980 election, tides turned as the incoming leadership received support from the United States, helping to restart the economy it had previously throttled under socialist leadership.

Volcano Crew on army truck, ©Beth Lesser

“Once the 80s came and the violence died down, people could go out again and the music began to take a more festive theme of being in the dance and celebrating,” says Beth Lesser, author of Dancehall: The Rise of Jamaican Dancehall Culture (SoulJazz Books), the definitive history of the era now back in print. Featuring 400 color photographs and interviews with luminaries including Sugar Minott, King Tubby, Prince Jammy, Jah Love, Little John, Barrington Levy, and Sister Nancy, Dancehall is an epic history of the era as told by the people who lived it. At almost 12×12 inches in size, the book is vinyl album size, every turn of the page a contact high, with Lesser’s kaleidoscopic portraits offering the perfect blend of insouciance and good times.

Hailing from New York, Beth Lesser landed in Toronto in the 1970s. Together with her husband, Lesser created Reggae Quarterly, to chronicle the culture. “We really liked the music of Augustus Pablo, so we wrote to him and said, we think your music is great, can we do anything to help promote your music here? And he actually responded,” Lesser remembers. “We made contact with people he knew and went to Jamaica to meet him to see what we could do.”

Chancery Lane loafer, ©Beth Lesser

Augustus Pablo saw the vision and had an idea of his own: expand the focus to include a broader range of producers, musicians and singers on the scene to widen the appeal and impact of Reggae Quarterly. Lesser was ready to get to work and immediately set off to meet the artists. “The first time we went, I didn’t even take a camera. I was not a photographer. I was a journalist, and I loved interviewing people. I loved writing. The first issue of the magazine, we just published with other people’s photos.”

Seeing Reggae Quarterly come to life, they realized the value of photographing the people they met. They returned to Jamaica, camera loadeds with black and white film, which was the industry standard. “At the time, color photography was just snapshots that you did at people’s birthday parties, it was not considered legitimate photography at all,” Lesser says.

Ghost Rider, ©Beth Lesser

But when they returned to the island and handed out prints, people were less than enthused with this turn of events. Realizing the stripped down aesthetic of black and white wasn’t hitting like color would, Lesser made the switch and began working in color film. Reggae Quarterly proved a true labor of love, a project made simply because it was fun. Can it be that it was all so simple then? Yes, and Lesser has the photos to prove it. “We would do an issue, and then we would sell it, and when we kind of recoup our money, we would do another issue, and then we sell it until we got the money back and could do another issue. So we got eight out in total,” she explains.

Their DIY approach to publishing extended to photography as well. Having no training, Lesser tapped into the camera’s effortless ability to engage and entertain. “It was about establishing a connection with the person and it was all very playful,” she says. “People were sitting around with nothing to do, and then you would come with the camera and they would all just jump in front of it, do silly things and everyone would laugh.”

Risto Benji in front of Jammy’s studio, ©Beth Lesser

Attuned to the natural flow of things, Lesser and her husband stayed in downtown Kingston without a car, preferring to take buses and walks, and building connections into friendships. In turn they were given extraordinary access, invited into people’s homes and studios, giving them deeper understanding of the relationships between artists and the collective approach to both business and making music.

“In Jamaica, the creative process is like a community process. It’s not one person who goes home, sits down with his guitar and writes a song,” says Lesser, who explains how it might all start one night at a dancehall, with someone chanting lyrics that inspires the selector to spin a track, a little more back and forth with the crowd getting hype. Then someone else take the studio to record over a different backing track and takes it to the dance where a singer hops on the track and gets a different reaction

Al Campbell at Skateland, ©Beth Lesser

“All these little people contribute to what ends up being one hit for one person,” says Lesser. “But that person sat down and wrote that hit, it came up through many layers and was contributed to by many people.

And that’s why it was so important to me to get pictures of everyone and put them all in the book and on my website. Because I felt that all these people were just as important in creating the song that became a hit.”

Jammy’s Crew outside the studio, ©Beth Lesser

You can follow Miss Rosen on Twitter