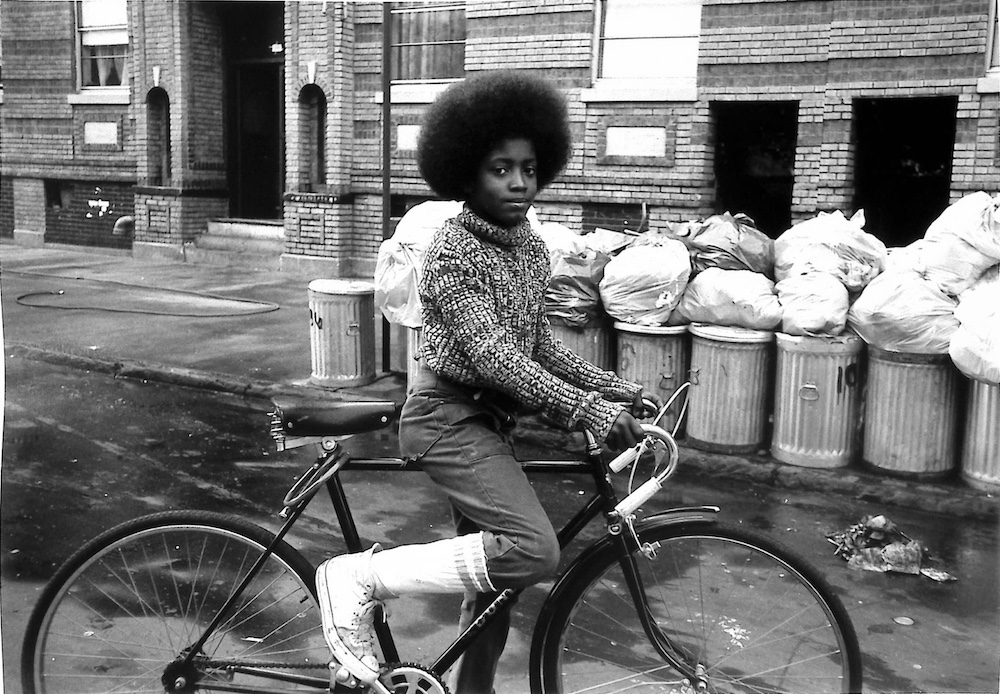

Boy with Afro on Bicycle in front of Trash Cans, (1975). Gelatin silver print. The New York Historical, Gift of Sally Klingenstein Martell © Estate of Arlene Gottfried

Back in January 2004, photographer Bruce Davidson unveiled prints from his fabled Subway series at Hermes on Madison Avenue. Amid the din of champagne glasses and chattering guests sprinkled across the mezzanine, Arlene Gottfried disappeared into the crowd, her unassuming presence a masterful disguise. She surreptitiously pointed an automatic camera in my direction. I saw the flash from the corner of my eye and swerved my head in time to catch a mischievous smile dash across Gottfried’s cherubic face, her eyes sparkling with delight as she held back a roaring laugh.

While everyone knows Gilbert Gottfried, the loud squawking comedian who became a household name as the Aflac Duck, few know that his sister, Arlene Gottfried (1950– 2017) was one of New York’s greatest photographers. Now the New York Historical Society revisits her singular career with the new exhibition Picture Stories: Photographs by Arlene Gottfried. The show brings together over 30 works from her extraordinary archive that effortlessly combines street, documentary, and portrait photography with the bawdy flair of a Brooklyn native who lived by her own rules.

Martell. © Estate of Arlene Gottfried

Hailing from Coney Island, Gottfried moved to Crown Heights just as white flight went into overdrive. With the rapid disappearance of the middle class, New York became a city of character, style, and grit, a home to street corner legends more than ready for their close up. In the 1970s, Gottfried moved to Greenwich Village and studied at the Fashion Institute of Technology, while her family settled on the Lower East Side. It was a full circle moment for the family: her grandmother, Minnie Zimmerman, first arrived on those very shores at the age of 14 back in 1910. A spry and spunky lady, Zimmerman lived to the age of 104, and passed along her lifelong love of wandering to her granddaughter Arlene.

Fresh out of school in 1972, Gottfried got a job at an ad agency and made ready use of the darkroom during off hours to print her own work made while cavorting at local beaches, parks, and nightclubs throughout the decade. Although shy and unassuming, Gottfried was equal parts bohemian and bon vivant who embraced the rough and tumble glamour of New Yorkers from all walks of life. She could be readily found among the trapeze artists at GG’s Barnum Room, swingers at Plato’s Retreat, or accompanying playwright and actor Miguel Piñero through the city’s more subterranean elements.

Martell. © Estate of Arlene Gottfried

Gottfried rarely gave interviews. Instead, she let the work speak for itself, her books published without written commentary of any sort. It was only in Mommie, her fifth and final book, that she decided to tell her story in print. “I look back at some of the magazines I did, because I’m trying to put things on my website, the way you put notches on your belt, and I wonder, ‘What did I do? What did that all mean?’” she said. “I made some money to make Cibachromes, because that was pricey. That’s what freelancing did for me, not much else. At least my books are from my heart, and that’s a whole other level of personal expression.”

For Gottfried, photography was not separate from life. She didn’t helicopter into someone else’s world, nor position herself as some sort of “objective” bystander and resell the images to the highest bidder. Instead, Gottfried made books born from the same impulse to make photo albums devoted to family, friends, and community. She photographed the Puerto Rican Day Parade over 20 years for Bacalaitos & Fireworks, but once again she was decades ahead of the curve. “The pictures were taken in Brooklyn, the Lower East Side, and the Bronx in the 1970s, 80s, and 90s. The book has a lot in my heart,” Gottfried revealed in Mommie. “I became close to a lot of people who began appearing in my photographs, as a natural progression. The people I photographed were my neighbors and friends. I was out there experimenting with my first camera: ‘Click! Click!’ It was all very connected to home in a way.”

Martell. © Estate of Arlene Gottfried

It was then that Gottfried met a young man named Midnight, who she would photograph for over 20 years. There is a self-portrait of the two standing together during the early years filled with smoldering passion and glamour. But soon Gottfried would receive a call from the New York Police Department: Midnight had climbed to the top of the Williamsburg Bridge earlier and had since been brought to Bellevue where he was diagnosed with schizophrenia. From then on, he was on and off medication, in and out of town, but Gottfried’s love and devotion never wavered despite the emotional toll she bore. “When I first put the work together, after it being in a box for years and years, we looked at it on the slide projector and we stood up from the table and he just reached out and shook my hand. He didn’t say anything. It let me know he was touched and he got it,” Gottfried remembered.

So as it is with everyone Gottfried graced with her camera, for she used her gifts to elevate the divine. Perhaps that was why she could sing gospel like Mahalia Jackson, possessed of the spirit that can be felt in every photograph she made.

Martell. © Estate of Arlene Gottfried

Martell. © Estate of Arlene Gottfried

Gottfried in memory of Arlene Gottfried. © Estate of Arlene Gottfried

Picture Stories: Photographs by Arlene Gottfried, is on view through May 25, 2025 at the New York Historical Society.

Follow Miss Rosen on Twitter