📷: Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

Decades ago, when American kids started engaging in wildly interesting and fun new activities such as skateboarding, graffiti, rapping, breakdancing and gaming, the media struggled in its attempt to define these emerging subcultures. Many of the vintage articles on these subjects share some common threads: they’re typically condescending, alarmist, and almost always warning of the dangers that these youth-oriented activities allegedly posed for children. Below is an assemblage of quotes from newspaper clips, circa 1960s-80s, that offer a glimpse into how reporters of yesteryear were describing what are today, some of the most foundational elements of pop culture worldwide.

WHAT IS A SKATEBOARD?

“What is a skateboard? Well, it’s a piece of wood, average about two feet long. Wheels are attached to the bottom. One foot is kept on the board while the other can be used to maneuver or make the board go faster on a flat surface.” (The La Crosse Tribune — May 23, 1965)

“From the California coast to the Boardwalk at Atlantic City, New Jersey, everyone seems to have the urge to go sidewalk surfin’. The lack of water and waves on the sidewalk calls for a surfboard with wheels and also a proper reduction in size—the skateboard. Measuring about 15 inches long and about 5 inches wide, the skateboard greatly resembles a roller skate with a board on top of it. That is just about what a skateboard is although there have been some slight changes.” (The Herald — June 2, 1965)

“Skateboards — small wooden platforms mounted on roller skate wheels—are being maneuvered through the streets of just about every city in the country. The skateboard, a sort of scooter with nothing to hold on to, is supposed to simulate some of the action one gets surfboarding in the ocean. You can lie or stand on it, hit 30 miles an hour going downhill, snake your way down the road, make 90-degree turns and take headers into a hedge.” (The Ottawa Citizen — May 7, 1965)

WHAT IS RAP?

“Rap music, the sassy new idiom of cool, cosmopolitan street blacks, has so captivated the young white audiences that it could possibly be the first form of black music since the so-called soul music of the late ’60s to win mass acceptance. The word ‘rap’—not to be confused with the Reynold’s stuff, a criminal charge or a slap on the face—involves speaking in a manner that is fast, witty and hip. There is little singing in rap music which is distinguished by its cocky attitude and funky, heavy and hip beat.” (New York Daily News — February 20, 1981)

“[I]n rap music, it’s not so much what say as how you say it and with the right rapper and a good get-down disco rhythm track, there’s a fair chance even Mother Goose could make it top the Top 40 these days. There are rap records on almost every subject and apparently, a market for almost every rap. Although rap music – basically rhymes that are spoken, not sung, over a bare-bones dance beat.” (AP — August 28, 1981)

“‘Rapping’ has become the hottest thing in progressive black music. Here’s how it works. First, you play that funky rhythm — and then manipulate the rhythm tracks electronically to get the tricked-up effects you want. Next add chanting voices that rhyme, alliterative, sputter and generally ‘rap’ over and around and under the percolating beat.” (The Morning News — April 26, 1981)

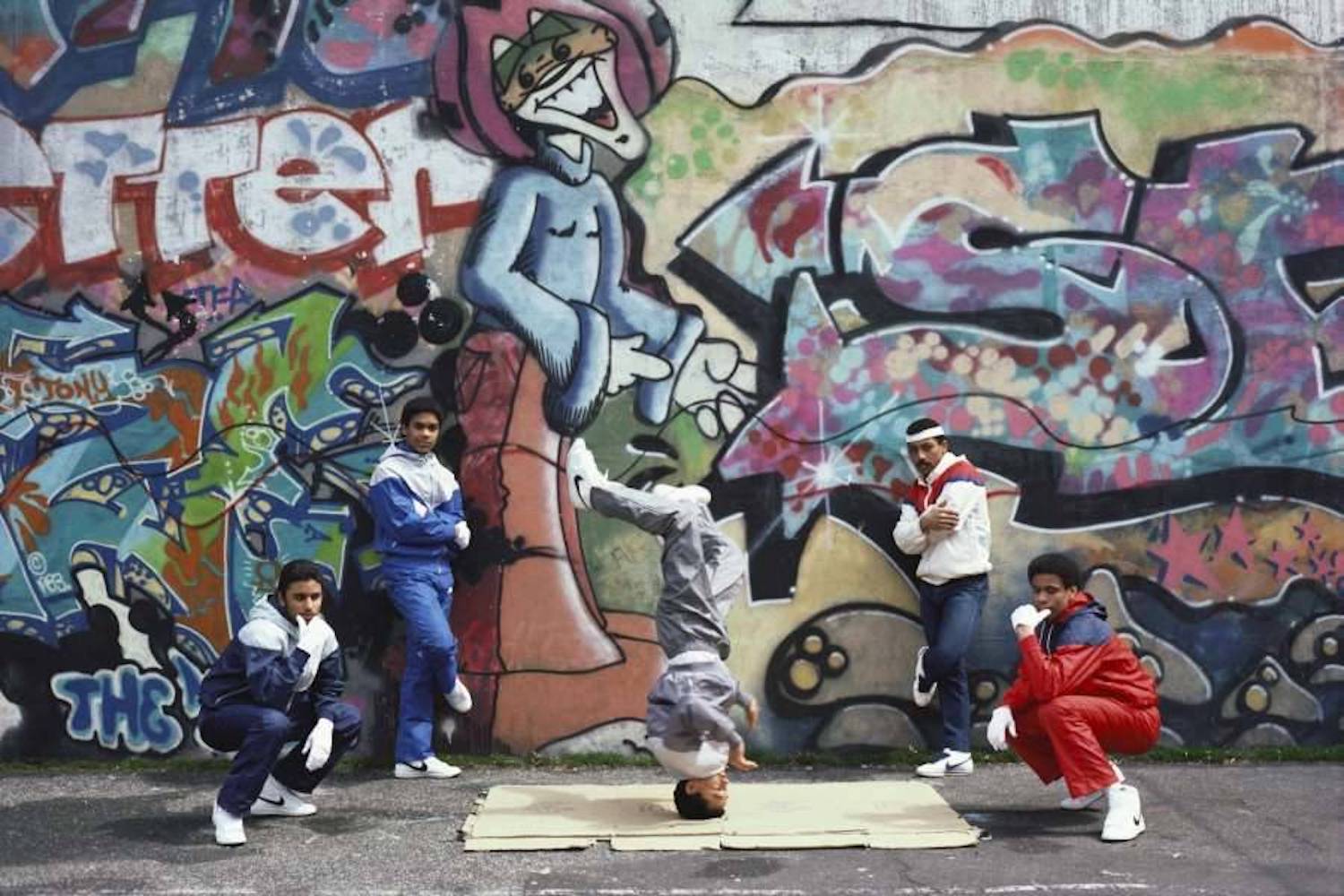

WHAT IS BREAKDANCING?

“This ‘latest’ dance craze – which combines mime and acrobatics, fluidity and great energy – has actually been around for 10 years, being developed on the streets of both the East and West Coasts. Lately it has emerged into the mainstream. A short break-dancing segment in the film Flashdance catapulted this street art into a worldwide phenomenon.” (CS Monitor — October 14, 1983)

“[T]he best way to describe breakdancing is that It’s fast, highly rhythmic, unpredictable, frenzied, incorporates elements of mime and is definitely a young person’s dance.” (Bernardsville News — November 2, 1983)

“And hip-hop devotees don’t merely dance to this music — they breakdance, a style consisting of wild, extraordinary moves as dancers spin on their hands, their backs — any part of the anatomy, in fact, that can support their body weight. You have lived until you’ve seen someone move to music by dancing on his neck.” (The Philadelphia Inquirer — October 9, 1983)

WHAT IS A VIDEO GAME?

“Last year’s TV ping pong is passé. TV screens this year can be turned into race tracks, basketball games and battlefields. A video game consists of a of a central console or control box which houses the circuitry and if needed, batteries. Most sets have optional AC adapters. Cassettes — about the size of a tape recorder cassette — are put in the console box.” (The Gazette — December 3, 1977)

“Video games offer striking visual treats on a television-like screen, such as bright flashes or color and light, and sound effects such as explosions, music and even speech. Equally important, the games demand split-second reactions by players who try to control the fast-paced action — and extend their playing time — through a small computer.” (Courier-Post — November 16, 1980)

“Video games are the new pastime — or waste time — of the young, sending the pinball machine the way of the horse and buggy. Developed on the heels of the rudimentary ‘Pong’ game of seven years ago, there are now hundreds of different, highly sophisticated video games earning billions of dollars across North America.” (The Gazette — April 30, 1983)

WHAT IS GRAFFITI?

“Graffiti is the Italian diminutive for ‘scratches,’ but there is nothing little about today’s graffiti and many of them are in technicolor. One of the most riveting inscriptions in Manhattan is a giant ‘Impeach Nixon’ in brilliant blue sprayed on the wall of the United Nation’s Plaza under the carved inscription: ‘They shall beat their swords into ploughshares…’

But names — shrill cries of ego in an unfeeling world — are by far the most common graffiti. Names come with numbers in New York, for example ‘Jose 126.’ This indicates the graffitist lives on 126th Street in Spanish Harlem. (UPI — June 11, 1972)

“The first time I saw the new graffiti—the stylish calligraphed and ornamented signatures of spray-can and marking-pen vandals—was three years ago in Philadelphia. I was dismayed by the near total saturation of urban surfaces: it made the whole city look as if it were slated for demolition. But I was also impressed by its artfulness and odd chasteness: there wasn’t a dirty word or even a ‘John loves Mary’ in sight. It was all pure primitive estheticism and self advertisement.” (New York Times — September 16, 1973)

“The nature of graffiti is less complex than the means of stopping it. More than 90 percent of the scrawls are first names accompanied by a street number or a Roman numeral. ‘Bing 170’ is typical of the signees.

‘Bing 170,’ ‘Joe 145,’ and ‘Pipilo 105’ are believed to to have been inspired to their destructive tendencies originally by a 17-year-old high school graduate from Manhattan whose signature was ‘Taki 183.’ Taki, whose real first name is Demetrius (he refused to divulge his last name), spawned the school of scrawl during the summer of 1970.” (The Baltimore Sun — December 10, 1972)