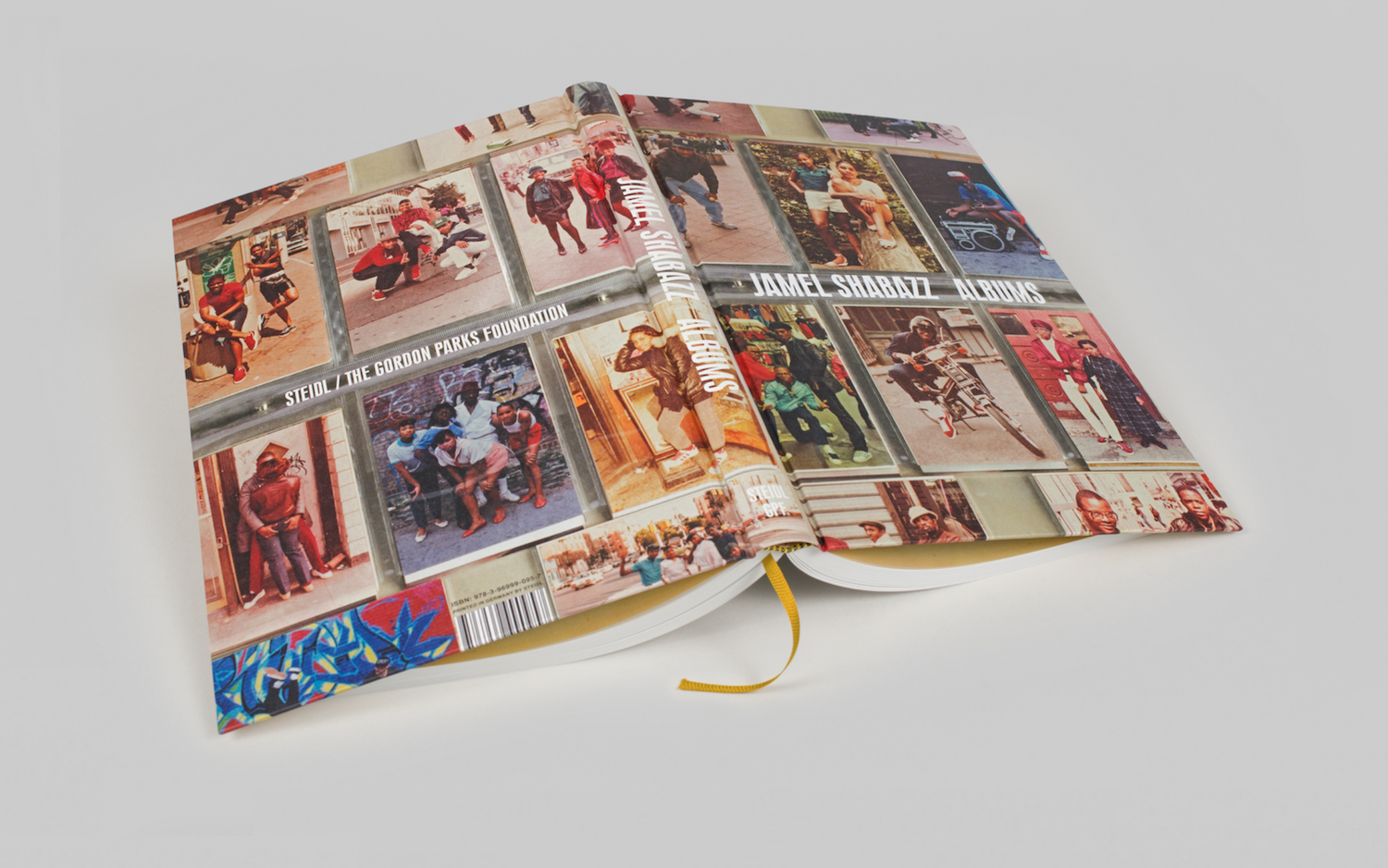

(Jamel Shabazz: Albums | Steidl/The Gordon Parks Foundation)

As a young boy growing up in Red Hook during the 1960s, photographer Jamel Shabazz lived in a mythic city that has long since disappeared but for the people, photographs, and stories that preserve a bygone era. His family lived in one of the newest Brooklyn housing projects replete with picturesque parks, baseball fields, Olympic-sized pool, and track for the community, many military veterans and their families.

Shabazz’s father had served in the Navy as a photographer, a calling he continued to honor and serve, turning his talents to the creation of the family photo album and collages. Tasked with preserving the family history and culture, he brought focus and discipline to the work, treating each image as an artifact to be passed from one generation to the next.

“I have very vivid memories of coming home for lunch from school and seeing my father, who would be home alone at his work space with a cup of black coffee and a bunch of 4×4 color and b/w photographs spread out on his desk,” Shabazz remembers. “His workspace was equipped with pencils for inscribing data on each image, scissors for making collages, and a magnifying glass searching for clues. He would be listening to some of the jazz greats, like Charlie Parker and Miles Davis playing on the turntable, which created a serene and relaxed atmosphere, while meticulously arranging prints into large photo albums.”

Shabazz noticed the process of making albums and collages had a therapeutic effect, inspiring him to reflect more deeply on the transformative powers of family photography as a form of legacy building. “It would take years later to fully understand the importance of this inherited process as it was all about making sure that our family history and the ancestors who paved the way were never forgotten,” he says

In the early 1970s, Shabazz and his family moved to the Flatbush section of Brooklyn just as it was transitioning from a historically Jewish-Italian community to a West Indian and Black American neighborhood, as Civil Rights protections finally began to roll-back the insidious de facto segregation practices that had shaped the landscape of New York for over a century. For the first time in his life, Shabazz was exposed to the racist violence and hatred that he had only previously seen chronicled on the pages of Magnum Photos member Leonard Freed’s seminal 1968 book, Black in White America: 1963-1965.

Long before Shabazz picked up a camera, he studied Freed’s book, which his father kept on the coffee table in their Red Hook apartment. Just nine years old, Shabazz looked at Freed’s photographs of the Civil Rights Movement at its peak, jotting down words he had never seen before like “rape,” “castration,” and “lynching” so he could look them up in the dictionary. He sat with the information, alone with only Freed’s pictures to help him understand what was happening.

By the 1970s, Shabazz had emerged as a photographer in his own right, making portraits of junior high school friends. He brought the film to be developed at a local pharmacy. “Each roll of processed film came with an inexpensive portfolio with plastic sleeves that had the store’s logo printed on them and accommodated 36 4×6 inch photographs,” says Shabazz, who set to work curating and sharing photography albums of his own.

After graduating high school, Shabazz served two years in the Army before returning home, and noticing a terrible change to the community. Gun violence was skyrocketing, leaving scores of young black men dead and locked up. But this was just a harbinger of what was yet to come once crack hit the streets. Shabazz resumed his photography practice with a clear mission in mind.

“With the escalating and senseless violence amongst those in my community that I encountered upon returning from the service, I knew that I had to take a proactive position and use all the tools I had to address this problem that was impacting people I knew directly,” Shabazz says. “I was out in the streets everyday documenting everything from homelessness, mental illness, prostitution, along with friendship, family and community. I put the work together in one main portfolio that I would carry around with me all the time and it became the introduction that I used to draw people in. I had tailored a specific portfolio for this very purpose; the images all documentary in nature and all told stories.”

With both camera and album in hand, Shabazz approached people who caught his eye, engaging young black men and women in conversation about their lives, challenges and goals. The album was the perfect conversation opener, allowing Shabazz not only to show his work but also create a space for reflection and discussion at the deeper issues his photographs raised.

“It is one thing to say that you are a photographer, but it is another to have proof of what you are able to do. By always having a photo album with me, people were able to better understand what I was doing,” says Shabazz. “The work in the albums sparked curiosity and interest, so I used these opportunities to have in-depth conversations about life and the importance of having goals and objectives, in addition to introducing them to the beauty of photography.”

With the publication of Jamel Shabazz: Albums (Steidl/The Gordon Parks Foundation), Shabazz goes back to his roots, unearthing the very photo albums he created between the 1970s and ‘90s. This book—awarded the Gordon Parks Foundation/Steidl Book Prize—presents, for the first time, Shabazz’s work drawn directly from his archive, and shows veritable slices of life with facsimile reprints of different pages and spreads from his many albums to recreate the experience for readers.

For fans of Shabazz’s work, Albums strikes an intimate note as it presents his seminal images in their original context, allowing readers to imagine themselves engaging with the photographs in their original form. Ever since his groundbreaking portfolio in the 100th issue of The Source back in 1998, Shabazz’s work has forged connections across generations and cultures, uniting people from all walks of life in a shared experience of love, pride, and joy — a providing what the artist describes as “visual medicine.”

“I learned early on the healing powers that photographs possessed,” says Shabazz. “I was 15-years-old when my parents divorced and started to lose my way. Viewing photographs in the local library exposed me to a world outside of mine. I saw that many people were suffering hardships and uncertainty and seeing those images humbled me and taught me lessons in gratitude and humility.”

Shabazz carried this wisdom as he grew into adulthood during the height of crack and AIDS while working as a New York City Correction Officer. The job was harrowing, exposing Shabazz to extreme violence, misery, and total disregard for human life.

“During my time working in corrections I would document various aspects of incarceration: from portraits of young men who were faced with long prison sentences to the horrors one could encounter caught up in the web of imprisonment,” says Shabazz. “The idea was to sway young people away from falling victim to the system due to making bad decisions. Some young men, who I knew personally, were under some strange illusion that going to jail was a rite of passage into manhood.”

To counter its effects, Shabazz carried his camera, making photographs during his commute, lunch breaks, and after work. “I felt it was my duty to go out in the streets and share my experience with the youth of my community,” says Shabazz. “I was on the frontlines both inside and out, so I could not sit back allowing all of this destruction to happen without lending my voice. Fortunately, I was able to aid a number of youth from the street life; some even went on to be correction officers, or city workers, and a few even became photographers and videographers.”

Over the years, Shabszz’s photo albums became restorative balms, creating a space where he could spend time with photographs that reflect love, humanity and innocence, giving him hope that helped sustain his journey, as well as honor the lives and legacies of those no longer with us.

“There are times in my life where I feel a great degree of hopelessness as I look at the present conditions of the world and all the lives that have been lost,” says Shabazz. “Since 2018, I have lost well over 90 friends, family members, and associates; and even as I write these words I am processing the death of two close friends who just died. To alleviate the pain and mixed feelings during those times I go to my photo albums, which allow me to travel back to a place and a time that I hold so many treasured memories of faces and places that no longer exist, but do in my photographs.”

You can follow Miss Rosen on Twitter and Instagram.

: (L) Slick Rick by Sophie Bramly (R) Slick Rick by Janette Beckman | Courtesy of TASCHEN Picture it: Detroit, the late 1980s. High school student Vikki Tobak awaited her turn to speak as the teacher asked the class: "What do you want to do when you grow up?" The…

: (L) Slick Rick by Sophie Bramly (R) Slick Rick by Janette Beckman | Courtesy of TASCHEN Picture it: Detroit, the late 1980s. High school student Vikki Tobak awaited her turn to speak as the teacher asked the class: "What do you want to do when you grow up?" The…