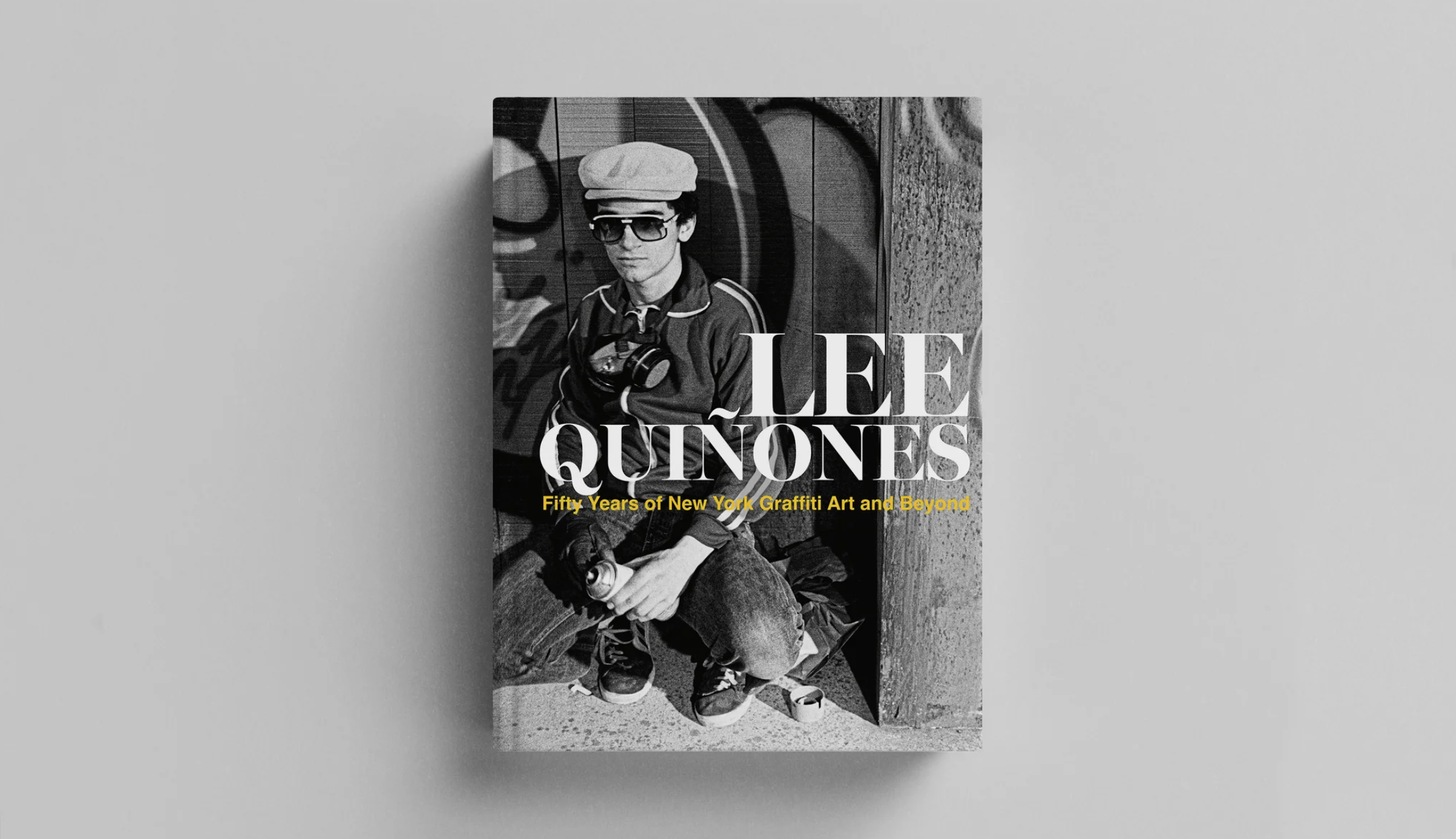

Cover of Lee Quiñones: Fifty Years of New York Graffiti Art and Beyond (Damiani Books, 2024). Photo by Chris Stein.

It’s been said that you can’t judge a book by it’s cover, which may be true among those who trade only in words but, for an artist the cover is paramount. It is the single image that embodies the wisdom of Aristotle (“the whole is greater than the sum of its parts”) without being flattened into a cliché. It is the promise of things to come, and when that promise is fulfilled, the cover becomes iconic. While time is the final test, few books have achieved this feat from day one: Jamel Shabazz’s Back in the Days, Larry Clark’s Tulsa, Jon Naar’s The Faith of Graffiti — and now Lee Quiñones: Fifty Years of New York Graffiti Art and Beyond (Damiani Books, 2024).

P.S.1 Contemporary Art Center, 1981. Photo by Martha Cooper

Lee Quiñones appears in a black and white photograph made by Blondie co-founder Chris Stein on the set of the “Rapture” music video in 1980. He’s crouched beside the last “E” in his first name, which appears on the wall behind him. He’s sporting a striped track jacket, jeans, and Pumas, newsboy cap topping the ensemble, looking at Stein thoughtfully through a pair of tinted Cazals. A respirator is slung around his neck, a recently used spray paint can resting comfortably in his hand, as he looks into the future.

Lexington Avenue IRT Express #5 subway train. Courtesy of artist.

By the time this photograph was made, Quiñones had taken subway art to new heights with his epic masterpieces that evoked the revolutionary spirit of artists like Diego Rivera, Eugene Delacroix, and Francisco Goya. He knew already knew a book was waiting to be written, one that he had finally begun to write the previous year. “I’ve been daydreaming about making a book since 1970s,” Quiñones says. “I started writing a book in 1979. I was thinking about the concept of a book, that, it could outlast the artists and it becomes the legacy, I needed to tell my story, because I couldn’t believe it myself at that point, and I still don’t.”

For Fifty Years of New York Graffiti Art and Beyond, Quiñones crafts a portrait of the artist as a boy becoming a man, and taking on the mantle of elder as new generations come of age following in his footsteps. Born in Ponce, Puerto Rico, in 1960, Quiñones moved with his family to Manhattan’s Lower East Side at the age of eight months. By five-years-old he was drawing, a process that allowed him to process the thing he was taking in as the city began to spiral into decline amid a barrage of benign neglect, white flight, and landlord sponsored arson. “I took in a lot of things that were happening around me, so I saw a fall from grace in the city and understood I couldn’t live by fairy tales anymore,” Quiñones says. “I needed to open my eyes and not just look, but see, and open my ears to not just hear, but listen.”

in.

As the city teetered towards bankruptcy in the mid-1970s, President Gerald Ford famously abandoned the city, effectively telling New Yorkers to “Drop Dead.” Residents rose to the challenge, displaying a level of creativity, innovation, and collectivism that remains unmatched to this day. With the emergence of graffiti, Hip Hop, disco, and punk, New Yorkers ushered in a new era of art, music, dance, nightlife, fashion, and film born of liberation. Against this backdrop the city became a canvas and life took on cinematic heights for those who dared.

ft. Photo by Martha Cooper

In 1974, three months before his 14th birthday, Quiñones took one of his very first adventures into the subway tunnels and never looked back. Over the next four years he embarked on a journey of discovery, mastering his hand to develop a visual language that would soon dominate the trains, while delivering a much-needed message to the public at large. In 1978, his vision crystallized in his first masterpiece, the Howard the Duck mural on handball wall at Corlears Junior High School. Quiñones transformed the massive concrete slab into a manifesto of sorts, proclaiming “Graffiti is an art, and if art is a crime, let God forgive us all” in the top left corner of the 17’ x 26’ wall.

Collection of KAWS.

As fate would have it, a young filmmaker named Charlie Ahearn happened upon the mural, and immediately took note. “I had been thinking, ‘A great artist is going coming from the streets,’” Ahearn told me in 2022. “I was looking at graffiti through the prism of Lee Quiñones’ murals, which were all over the Lower East Side — and I was like, ‘He’s right here!’” In 1980, the two would finally connect and go on to collaborate on Wild Style, the first hip hop feature film, which case Quiñones in the starring role of Zoro.

Photo by Jason Mandella

By that time, Quiñones’s whole cars had taken the city storm, redefining the very possibilities of public art. Under the cover of night, he crafted majestic meditations on modern life that heralded the arrival of a new era. In 1977, he painted Jesus Christ Superstar (Heaven Is Life, Earth Is Hell), a whole car top-to-bottom, end-to-end “married couple” (two permanently interlocked subway cars, each 7’ x 104’ in size) on the 5 line — a visionary act that leveled the supposed hierarchy of “high” and “low” art.

Advertisement for New York/New Wave at P.S.1 Contemporary Art Center in ArtForum. Photo by Bobby

Grossman

“I had to get past those theoretical limitations that people put upon me because they weren’t understanding it,” Quiñones says. “But I understood myself enough to say, I’ll keep the light on for you. To most people a whole car is unfathomable. Even writers say, how did you do that? To me, whole cars are a precious celebration. I am guided by persistence, consistency, some kind of master plan so that the more people said no, the more I said yes to myself.”

Private collection.

It’s a mindset Quiñones has maintained from the outset, one that has served him for half a century and looks to a future where the old hierarchies, once broken, remain well trampled underfoot. “I’m not comfortable being comfortable,” he says. “I was on a mission then as I am right now. I want to be in the driver’s seat; I need to guide my own soul and find another platform that extend itself much more than what I did in those tunnels. In the most claustrophobic place I felt that I was riding my wings. To me I’m always in a tunnel, but I have a vision — tunnel vision — and I’m always finding my way to that light.”

132 x 109 in. Photo by Jason Mandella

one custom record with recordings by the artist housed in a vintage suitcase with an individual can of

spray paint from the artist’s collection. Edition of 12, 4 artist proofs, 2 printers proofs. Courtesy of LeRoy

Neiman Center for Print Studies at Columbia University.

Follow Miss Rosen on Twitter