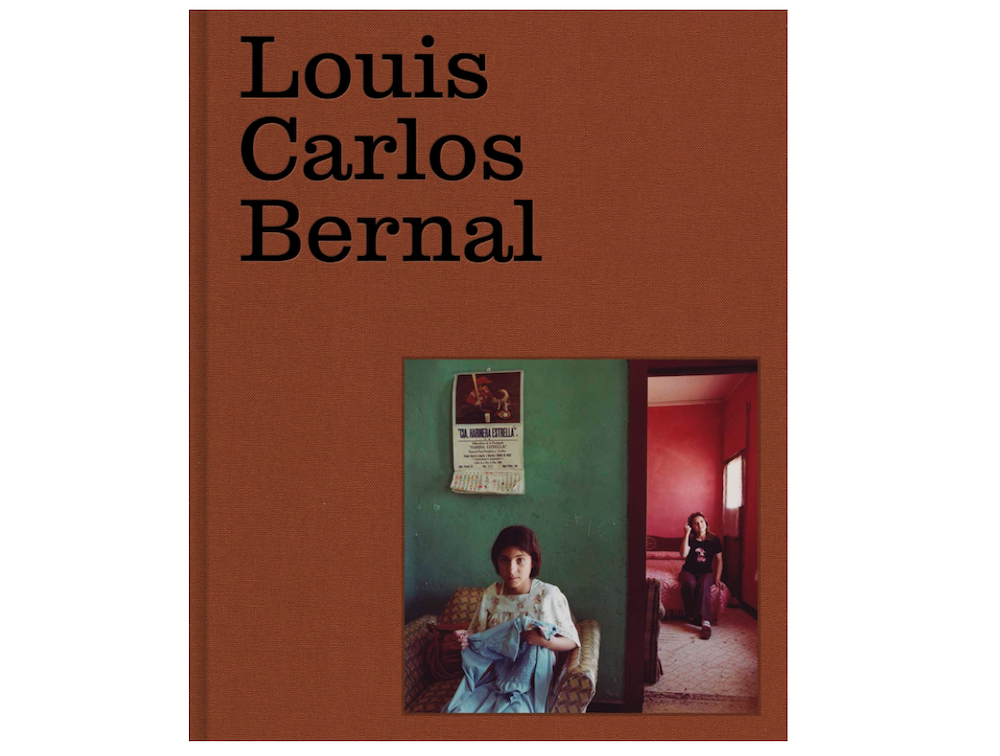

Front cover of Louis Carlos Bernal: Monografía (Aperture, 2024); cover image: Louis Carlos Bernal, Dos Mujeres, Douglas, Arizona,1978. © Lisa Bernal Brethour and Katrina Bernal. Courtesy Center for Creative Photography, University of Arizona: Gift of Helen Unruh.

In 1836, just one year before Mexico outlawed slavery, a province in the north went rogue and declared independence. For nearly a decade, the Republic of Texas stood on its own, until it’s economic fortunes took a precipitous turn for the worse, brokering a deal to join the Union as the 28th state in 1845 and sparking the Mexican-American War. Both nations, newly formed on stolen lands, were locked in a battle for the lands of the Southwest, some 529,000 square miles that have been home to indigenous peoples for more than 12,000 years. Following their defeat in 1848, Mexico ceded what would become California, Nevada, Utah, Arizona, and New Mexico for a mere 15 million ($586.4 million today), leaving many Mexican Americans dispossessed and impoverished.

Louis Carlos Bernal, Dos Cholas, Tucson, Arizona, 1982; from Louis Carlos Bernal: Monografía (Aperture, 2024). © Lisa Bernal Brethour and Katrina Bernal. Courtesy Center for Creative Photography, University of Arizona: Louis Carlos Bernal Archive.

While tensions between the North and the South reached a fevered pitch around slavery, these ancient lands were reimagined as the frontier where white Americans could cast their fates against nature and the “merciless Indian savages” described in the Declaration of Independence. Just one year, the nation was gripped with gold fever, sparking off the California Gold Rush and signaling the birth of the Wild West. But within four decades, the frontier would become a thing of the past, the mythic image of rugged individualism inscribed into the marrow of every red-blooded American male as birthright and ideal.

But were it not for Mexican culture, there would be no cowboy — an archetype rooted in the vaqueros of the 16th and 17th centuries, that takes its very name from a racist slur against Black American cowhands. Much in the same way, the history of Mexican Americans living on vanquished lands their ancestors called home have survived over the past two centuries in the luminous incarnation of Chicano culture. And while it has unequivocally shaped youth culture from Zoot suits to lowriders over the past century, Chicano artists have largely gone overlooked by the establishment.

Louis Carlos Bernal, Albert y Lynn Morales, Silver City, New Mexico, 1978; from Louis Carlos Bernal: Monografía (Aperture, 2024). © Lisa Bernal Brethour and Katrina Bernal. Courtesy Center for Creative Photography, University of Arizona: Gift of the artist.

Few see absence as clearly as those ignored, an insult made all the more injurious by the false images propagated in its place. From the moment Texas was annexed, the nation began to vilify people whose lands they colonized — a practice we see with President Biden’s sweeping anti-immigration policies that are even more encompassing than those of his predecessor. But the spirit of resistance, which took root during El Movimiento (the Chicano Movement) of the 1960s continues today, drawing inspiration from artists like Louis Carlos Bernal (1941–1993), the “father of Chicano art photography.” Hailing from the small, isolated border town of Douglas, Arizona, Bernal’s family moved to Phoenix to build a better life for their young child. At the age of 11, Bernal got a camera and began making photographs, developing a passion that would guide him through life. He enrolled in Arizona State University and received his MFA in 1972 at a time when institutions largely excluded photography from the ranks of fine art.

“It was an awakening. Bernal began to see that what he really wanted to do was art and express himself through the medium of photography, rather than follow career mode like photojournalist or commercial photographer,” says Elizabeth Ferrer, author of Louis Carlos Bernal: Monografía (Aperture), the first major survey of the artist’s work published in conjunction with an exhibition of the work at Center for Creative Photography’s Center Galleries in Tucson from September 14, 2024 – March 15, 2025. The book traces Bernal’s evolution as a conceptual photographer, exploring his early experiments in black and white, where he hones an talent for crafted intricately layered environmental portraits of Mexican-American life. Bernal’s early work parallels the heights of El Movimiento, which centered the idea of Aztlán, the mythic homeland, alongside calls for sovereignty and self-determination. Chicano college students took to the streets in protest of Vietnam War, which disproportionately sent Black and brown youth to the frontlines only to return in body bags. At the same time, Cesar Chavez lead the fight to unionize farm workers, bringing their plight to national attention for the first time and forging a new image of Chicano pride.

Louis Carlos Bernal, Santos y Television, Mexico, 1981; from Louis Carlos Bernal: Monografía (Aperture, 2024). © Lisa Bernal Brethour and Katrina Bernal. Courtesy Center for Creative Photography, University of Arizona: Louis Carlos Bernal Archive.

“Bernal began thinking about what it was that made him a Chicano and made a decision in 1973 to move away from experimental work that would have branded him as an artist with a camera, to doing direct photography,” says Ferrer. “He went around to the barrios of Tucson and eventually throughout the Southwest, meeting people, getting invited into their homes, and then making these works, which could be mistaken for documentary photography.”

Bernal was not on “objective” observer using the camera to formally record the visual world; rather he was a collaborator who used photography to craft intimate, layered stories of people and place that honored Chicano identity, family, and community. “His photographs involve a careful balance of staging and posing, and working with the found environment with lights, but then making these very direct, honest photographs of Mexican-American people in a way that they had never been depicted before,” Ferrer says. “They are not ‘subjects’ in an anthropological sense, but people that deserve to be seen with integrity and love. He was able to make these photographs because he knew where they were coming from.”

Louis Carlos Bernal, Juanita Serrano with Santo Niño de Atocha, 1978; from Louis Carlos Bernal: Monografía (Aperture, 2024). © Lisa Bernal Brethour and Katrina Bernal. Courtesy Center for Creative Photography, University of Arizona: Louis Carlos Bernal Archive.

At a time when the academy largely regarded color photography as “low art,” Bernal decided to switch from black and white to color to make these works, recognizing the psychological power the full spectrum of color brought to his images. To offset the considerable expense of color film and processing, Bernal received grants throughout his career, while also running the photography program at Pima Community College in Tucson. His method was described as “frugal,” knowing how to get the best results by maintaining a disciplined approach. Within a single frame, Bernal distilled the luminous spirit of Chicano life, creating portraits layered with power and pride, revealing stories of a people as told from the inside looking out.

Louis Carlos Bernal, Cholos, Logan Heights, San Diego, 1980; from Louis Carlos Bernal: Monografía (Aperture, 2024). © Lisa Bernal Brethour and Katrina Bernal. Courtesy Center for Creative Photography, University of Arizona.

Louis Carlos Bernal, Helen, 1988; from the series Lubbock; from Louis Carlos Bernal: Monografía (Aperture, 2024). © Lisa Bernal Brethour and Katrina Bernal. Courtesy Center for Creative Photography, University of Arizona: Louis Carlos Bernal Archive.

Louis Carlos Bernal, Mexican Escapade, 1974; from the series An American Fairy Tale; from Louis Carlos Bernal: Monografía (Aperture, 2024). © Lisa Bernal Brethour and Katrina Bernal. Courtesy Center for Creative Photography, University of Arizona: Louis Carlos Bernal Archive.

Follow Miss Rosen on Twitter