© Leonard Freed / Magnum Photos

If Rome is the Eternal City, New York is its twin flame: a gritty, glittering town built on the backs of empires won and lost, reduced to rubble and reborn like the phoenix. After ignoble defeat in World War II, Italy reemerged as a a beacon of culture and style with La Dolce Vita in the 1960s. But underneath the sparkling veneer, the dark, relentless shadows of Neo-realism lurked. Here the brutal cost of modern life was exposed, a world filled with victims, villains, and outlaws. It was catnip for a new generation of American filmmakers like Martin Scorsese and Francis Ford Coppola who saw in Little Italy a kindred spirit. With the epic collapse of New York in the 1970s, Hollywood closely followed suit, crafting a wealth of neo-realist copaganda films and TV shows that cast police officers as rugged anti-heroes locked in battle with the underworld. Reality was less flattering. They were simply working class high school graduates willing to do the bidding of the state.

“When asked why I became so interested in the police, I have to answer, everyone should be. If we do not concern ourselves with who the police are – who they really are — not just ‘cops’ or ‘pigs,’ ‘law enforcement officers’ or ‘boys in blue,’ we run the real risk of finding that we no longer have public servants who are required to protect the public, but a lawless army from which we will all take orders,” photographer Leonard Freed (1929–2006) wrote in Police Work, first published in 1980. After documenting Black life across the nation during the mid-1960s at the height of the Civil Rights Movement, the Brooklyn native and celebrated Magnum Photos member returned home and embarked on a decade-long journey behind the thin blue line. Between 1972–1979, Freed chronicled life on the beat with a blend of admiration, sentimentality, and paternalism, interspersed with stark scenes of violence, brutality, and death.

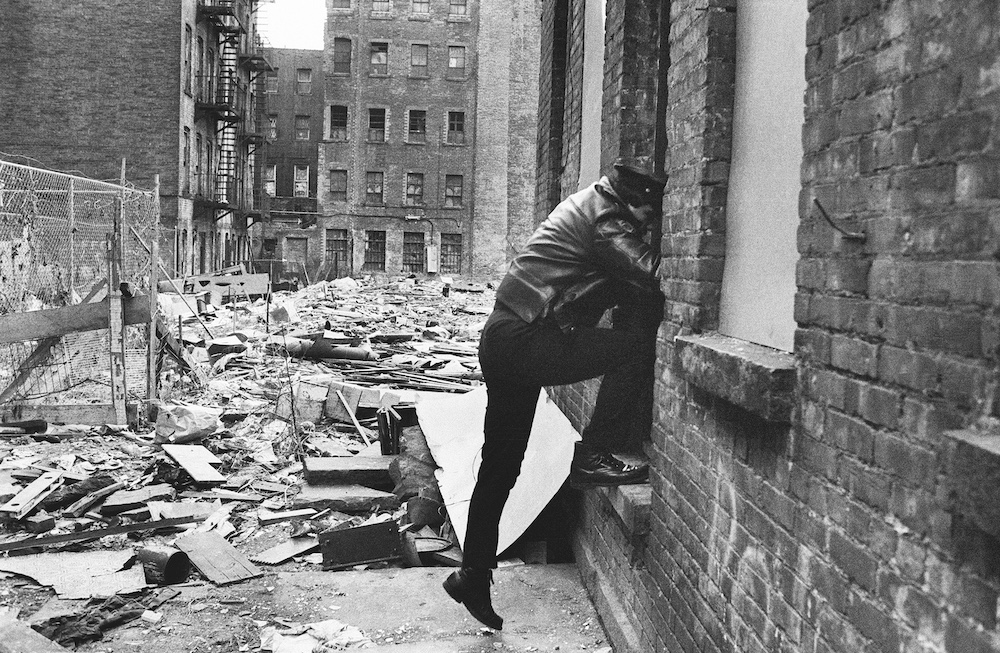

Now back in print, Police Work revisits Freed’s cinematic portrait of pathos amidst a harrowing landscape of poverty, crime, addiction, and violence, the gristly meat and potatoes of copaganda. The book integrates elements of the procedural with narrative flair as Freed takes us inside the belly of the beast, with voices from those in the pictures woven into a series of captions that opens each chapter with a bang. “The Raid” begins with a beat cop climbing into a dilapidated building in a war torn vacant lot. Like all photographs, the location and date are undisclosed. The lack of context adds a layer of mythos and ambiguity, enhancing the emotional drama of the images.

“An abandoned building. Inside, the officer found a ‘shooting gallery,’ where drug addicts go to buy dreams or to die,” Freed writes with prosaic flair. It’s equal parts caption and soundbite, evoking the dulcet tones of Sue Simmons reading a teaser for tonight’s “Live at Five.” Freed arrived on the scene after the large-scale police action went down in ignoble defeat. Some dozen undercover officers enlisted a battering ram and hydraulic drills to get inside the steel doors. Inside they found two men, one woman, boxes of packaged drugs. The bust was a bust, but Freed struck gold, the filth and the squalor torn straight from the pages of How the Other Half Lives with a 1970s twist.

Freed takes readers from “The Precinct” on “Patrol” for both “Day Shift” and “Night Shift,” visiting “Crime Scenes” and “Code DB” (dead body). He follows “Arrests” to the “House of Detention,” the last stop for the nameless people whose faces float in and out of the book. Pushers, pimps, prostitutes — their fate is now left to the courts. Innocent or guilty, their story is presented through the police version of events. Freed whisks us off to a “Police Funeral” then closes the book with a chapter titled “Family Values,” a catchphrase televangelist Pat Robertson famously popularized during the 1992 Republican National Convention. It’s an apt conclusion for the book, which calls to mind the words of George Orwell, who reportedly said, “Journalism is printing something that someone does not want printed. Everything else is public relations.”

“When asked if I saw brutality and corruption I have to answer, of course not,” Freed wrote in 1980. “What I saw were average people doing a sometimes boring job, sometimes corrupting, sometimes dangerous and ugly and unhealthy job. I hope to make people think about who the police are and why we need them.” But readers may wonder, is such a thing possible within the framework of Empire? In an effort to “humanize” a dehumanizing job, Freed leaves the reader to make sense of the relentless carnage that laid New York to waste without a clue how or why.

The landscape is scarred by the invisible hand of Richard Nixon who simultaneously flooded Black and Latino communities with drugs while stripping them of basic government services by defunding fire, sanitation, and police departments. His successor, Gerald Ford, refused to bail out the city in 1975, effectively leaving it for dead. White flight decimated the city’s economic base as middle class families decamped for the suburbs, where they could safely watch the Bronx burning during the 1977 World Series, never realizing landlords hired arsonists to torch these properties as part of a widespread practice of insurance fraud.

But perhaps most tellingly, in 1972 Knapp Commission found corruption rampant throughout the NYPD, exposing a deeply entrenched culture of organized crime. Who is the real criminal, you might ask. The best copaganda blurs the lines between art, entertainment, news, history, capitalism, fascism, illusion, and myth. It relies on symbols and dogwhistles, flags, uniforms, badges, medals, and your faith that those armed to serve and protect the State will do the same for its citizens.

Follow Miss Rosen on Twitter