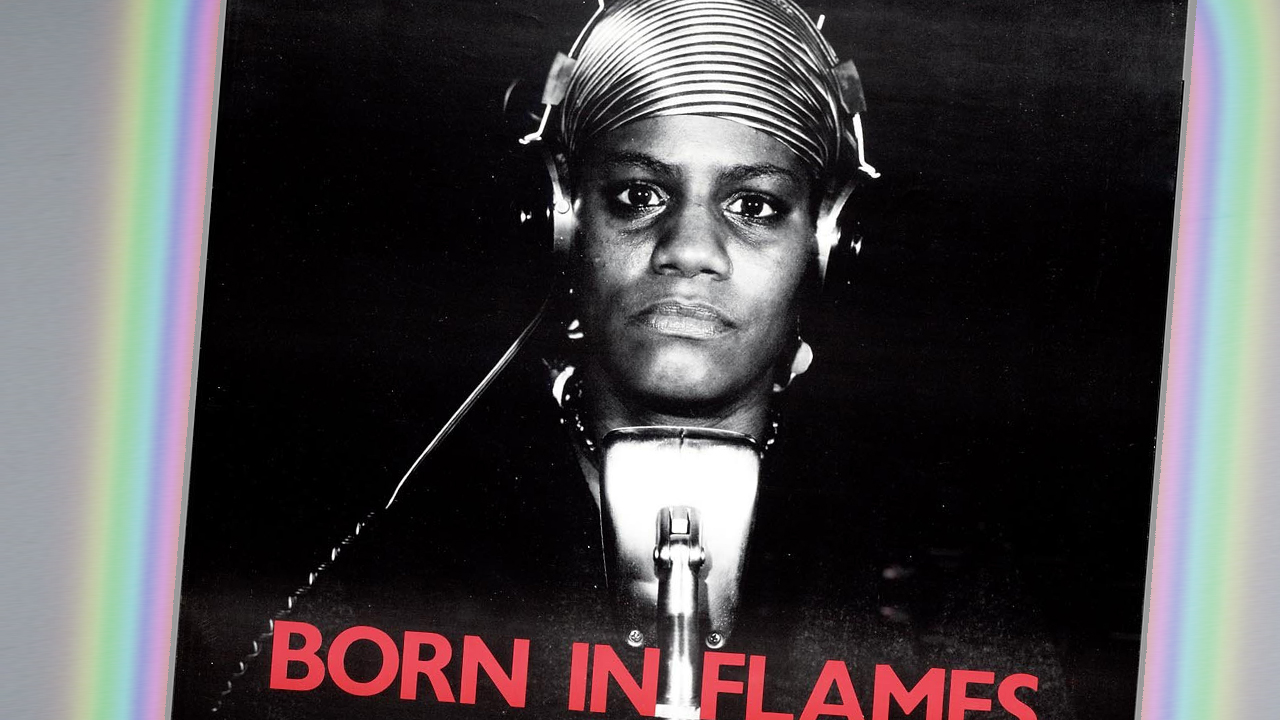

ANIMAL’s Radicals Of Retrofuturism uncovers stories by the technological rebels of the past in vintage media and looks at their predictions in the context of today’s digital world. This week we discuss Lizzie Borden’s early 1980’s feminist sci-fi film Born In Flames.

Born In Flames, director Lizzie Borden‘s critic-maligned 1983 radical feminist film, is often described as “sci-fi,” but the reality she imagines is so far removed from our own, it’s tempting to label it “fantasy.” Her film depicts a rare fictional future in which technology doesn’t seem to have advanced, nor has the fashion or lifestyle. What has changed is that ten years prior to the unstated year of the film, a socialist revolution took over the U.S., leaving us with the first “truly democratic” socialist government. As the film begins, the country is celebrating the anniversary of this revolution, but the movie’s stars, many of which were real-life political activists, are not at all satisfied.

The women of the film, many of whom are black and queer, demand more than their socialist government is wiling to give. This is a fairly amazing concept in itself — at the beginning of the Reagan era, one year before Madonna’s “Material Girl,” Borden’s film imagines a world where socialist revolution has already occurred and, according to her characters, it isn’t good enough. For the women of the film, the utopia their society claims to be is a lie. Violence against women is still rampant, and there are accusations that the government is unfairly employing people based on gender and race.

Much of the film consists of realistic discussions between factions of radical feminist movements: the anti-hierarchical “Women’s Army,” who believe women should be ready to take violent action against those that threaten them, two pirate radio stations, which serve as the film’s chorus, and three intellectual white interns at a prominent socialist newspaper, who feel extreme feminist separatism is tearing the movement apart. All of these positions have been taken over and over again throughout the history of leftist politics.

“All oppressed people have a right to violence,” activist Flo Kennedy posits. “It’s like the right to pee: you’ve gotta have the right place, you’ve gotta have the right time, you’ve gotta have the appropriate situation. And believe me, this is the appropriate situation.”

Halfway through the film’s 80 minute running time, a black activist named Adelaide Norris, who is suspected by the government of smuggling arms from Africa, is arrested and dies in jail under uncertain circumstances. The authorities deem it a suicide, which prompts a wave of anger, uniting the fractured feminist fronts against the status quo. The scenes of protest in response to the unjust death of a black woman are not far off from the images coming from Ferguson since the death of Michael Brown.

One of the few pieces of technology, other than radio equipment, in the film, appears when two of the black feminists play the early video game Space Invaders while they talk. This casual display of black, queer females engaged in a popular video game shouldn’t seem as out-there as their attempts to buy automatic weapons, but a day after present-day feminist game critic Anita Sarkeesian had to leave her home over fear of death threats, this quiet little scene feels uncomfortably timely.

Riot grrrl founder and Bikini Kill and Le Tigre member Kathleen Hanna used to give autographs that read simply, “Kathleen Hanna. Born In Flames,” telling fans, “You have to see this movie.” She told The Dissolve why she feels the film is so vital.

[Lizzie Borden] finished it, and that’s the whole thing. So much of this shit gets started and doesn’t get finished because there’s no money, and because people don’t have the longevity to keep shooting and editing and all this stuff. The thing about the film is just that it exists.

Borden has said the point of her film was to “rekindle hope,” to “present some images of something that was different— not a blueprint for revolution.” In Kathleen Hanna’s interview with The Dissolve, she said the room given for imagination, for questions without answers, what what drew her to the film as the riot grrrl movement began. Both women have been criticized for presenting problems without offering solutions, and today, we continue to struggle to find resolution for these still very relevant issues.

The film ends on an invigorating, almost Bonnie And Clyde-esque note, as the team of feminists steal two U-Haul trucks to serve as their newly collective mobile radio station before hijacking the president’s speech by ominously blowing up the antenna on the roof of the World Trade Center.

Today, such drastic action wouldn’t be necessary: we can livestream video from anywhere, photograph dissent and injustice on our phones and immediately send it to anyone on Earth with an internet connection. As Gil-Scott Heron famously noted, revolutions are birthed on the backs of the media that carry them. Thirty years after its release, Born In Flames forces us to envision the possibilities implicit in our communication.

The entire film is available on Youtube, embedded below.