Rjyan Kidwell’s work as Cex has long been fueled by provocation. Consider a performance the electronic musician, Tigerbeat6 cofounder, and turn-of-the-millennium internet hero gave in 2007, opening for Dan Deacon and Girl Talk. After he was lifted on stage in a wheelchair, Cex told the crowd he was a contest-winner hoping to raise awareness for a made-up disease called “Pussy Hook-Up Voice,” then launched into a set of nasty dialogue from porno flicks and tortuous yelling over techno. It was, Kidwell says proudly, “the most explicit thing I could have imagined.”

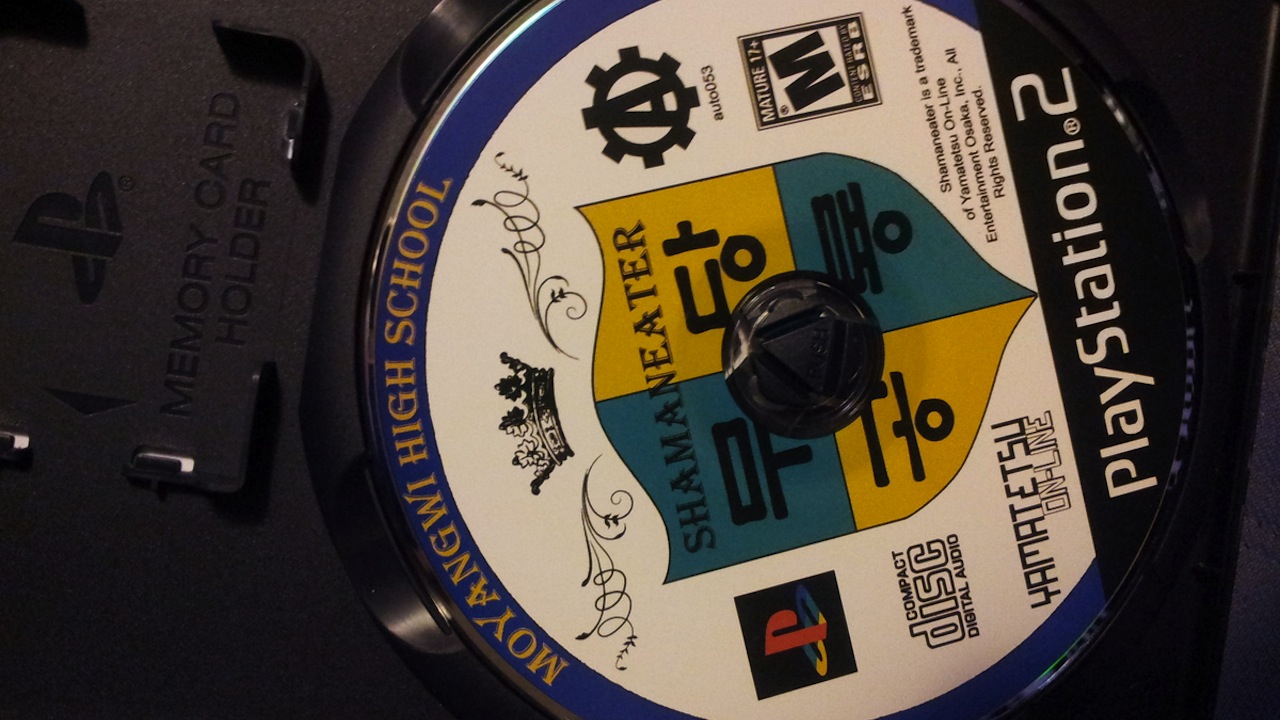

Cex’s latest work, the album Shamaneater, is an imaginary soundtrack to a fictional 2001 Playstation 2 game of the same name, and continues in this trollish but deeply felt tradition. To accompany the music, Kidwell created an elaborate Game FAQ – a type of user-created strategy guide that was popular during PS2’s heyday – to walk listeners through Shamaneater’s universe.

Each of the record’s 12 tracks of skittering, sprawling electronica, lovingly crafted with outdated digital hardware, corresponds to a level in the game. Taken as a whole, the album is a stiff-upper-lip elegy to a bygone gaming era and a rumination on the alarming rate at which technology fades away.

The musical worlds in these songs are immersive: Meathead nu-metal on “Ritual”; Coughing, flickering funk on “Micro”; ten-minute long, man-on-mission music on “Vapor Ops.” Each of the compositions was culled and cut down from improvisations that sometimes lasted as long as an hour. Exhibiting a Brian Eno-like embrace of creative obstacles, Kidwell explains that using “obsolete” digital instruments was “calming and inspiring,” unlike working with a computer program’s “infinite choices” which he describes as being artistically “paralyzing.”

Once he had his cyberpunk instrumentals completed, Kidwell decided to surround them with meta-fictional conceit. A number of ideas that would have involved intense outside collaboration (a Manga-inspired comic book, an elaborate Internet hoax perpetuating the myth that Shamaneater was a real PS2 game, a video game manual), were nixed for the simple, evocative text-based GameFAQ — something he could sit down and create on his own.

Shamaneater is not a precious piece of nostalgia. Despite Kidwell’s dedication to capturing the voice of the amateur FAQ scribe, parsing the internal logic of an imaginary video game he invented, and the atmospherics of some truly excellent video game music, Shamaneater is a harsh reminder that shit’s always changing and things are always dying out. Forgotten games on an obsolete console make that idea tangible.

The album art for is a photo of an overflowing shelf of old PS2 games in yellow envelopes at a Gamestop: games that were once 60 bucks and packaged properly, relegated to a mess of cheap sleeves and priced at just a few bucks. Physical copies of Shamaneater come packaged in a dirty, old Gamestop cases. “Personally, I’m not sad about [these technological changes],” Kidwell makes clear, “But I do think it is sad because it’s very representative of the bigger thing” – that we’re swimming around in a culture that is pathologically focused on “newness.”

The album art for is a photo of an overflowing shelf of old PS2 games in yellow envelopes at a Gamestop: games that were once 60 bucks and packaged properly, relegated to a mess of cheap sleeves and priced at just a few bucks. Physical copies of Shamaneater come packaged in a dirty, old Gamestop cases. “Personally, I’m not sad about [these technological changes],” Kidwell makes clear, “But I do think it is sad because it’s very representative of the bigger thing” – that we’re swimming around in a culture that is pathologically focused on “newness.”

Kidwell describes this fact as a kind of “ambient sadness,” connected to gut-level icky realizations about the modern world: How iPhones are designed to break so you have to buy a new one if you drop yours more than once; the all-encompassing, expression-stifling corporate control of the web; that online life is a nerve-wracking extension of real life rather than a positive, limitless alternative. In Kidwell’s words, they’re “things you can’t think about too much because there’s nothing to think about.” “Yeah, that’s kind of a bummer, but we all still have to live,” he adds with a happy-sad cackle.

Shamaneater is a levelheaded lament from a creative person who has been at it for a long time and continues to make compelling work, but who is painfully aware that his supposed “moment” is over. Not because of anything he did or didn’t do, but because everybody’s moment is over eventually. “I’m 15 years removed from my newness,” Kidwell points out soberly. “I feel like a Playstation 2 game all the time.”