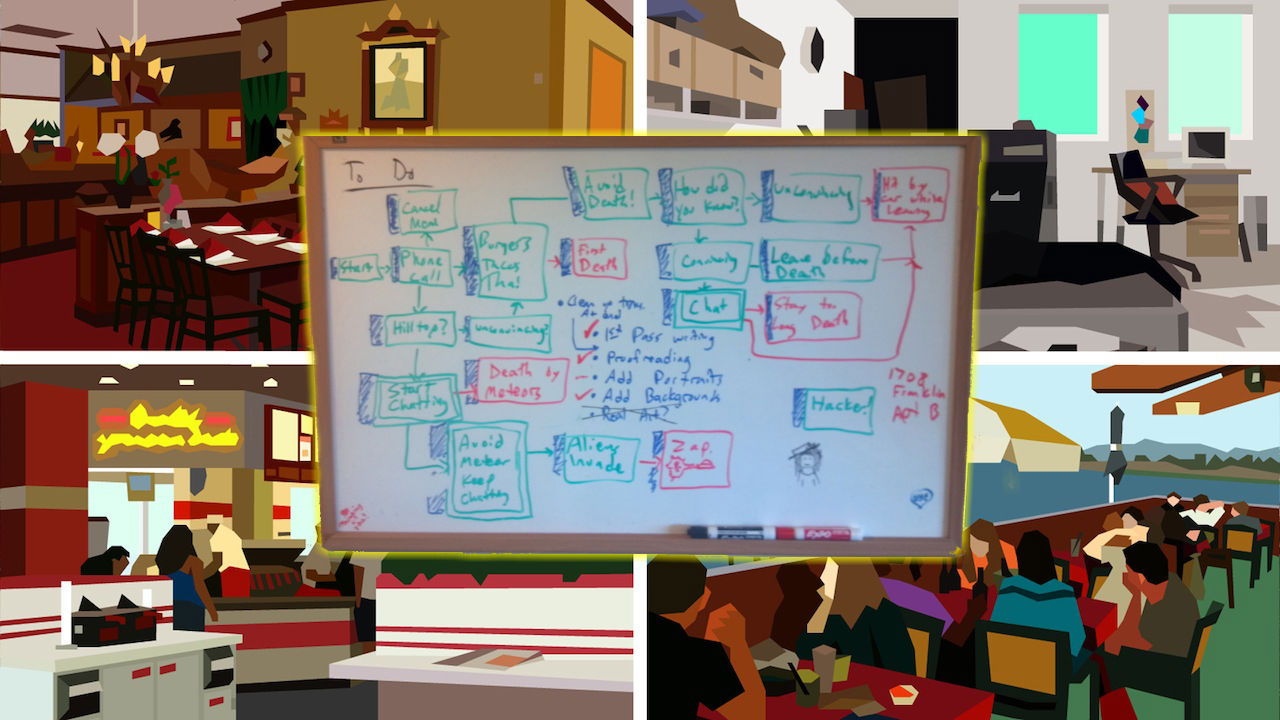

ANIMAL’s Game Plan feature asks video game developers to share a bit about their process and some working images from the creation of a recent game. This week, we spoke with Chris Cornell of Paper Dino about Save the Date, a fourth wall-breaking dating game that gets stranger every time you play it.

There is a genre of video game called the “dating sim.” It can get pretty weird, and Chris Cornell’s Save the Date lives up to the standard set by its predecessors (and then some). But the starkly illustrated game reaches new levels of meta-ness while telling a surprisingly touching story, entirely in text dialogue, about a girl who can’t stop dying—and whose life you desperately want to save.

It begins innocently. The phone rings—it’s your date, Felicia. You decide to get Thai food, or burgers, or tacos. You order. Make small talk. Things are going well—then Felicia dies. She has an allergic reaction, or there’s a gas explosion, or the restaurant is stormed by ninjas. You start over, determined to do better, and this time you have the option to warn her. “Actually, the Pad Thai has peanuts in it.” Etc. Disaster is averted. When she asks you how you knew, you can tell her you’re psychic, or you’re a wizard, or you’re from the future—or that you’re playing a video game, and you’ve seen her die this way before. That’s when things really get strange. Cornell tells Animal:

From my point of view it was really exciting, because this was a story I actually could not think of any way to tell other than the game I was envisioning. To me that’s kind of neat. The reason that I hoped it would work was because it was going to deliberately involve the player as a participant in the story. That would be very difficult to reproduce with anything that didn’t have a player that was participating.

Of course Felicia doesn’t believe you’re psychic, or that you’re a wizard. You can’t even guess the number she’s thinking of—and you didn’t even know about the letter she sent to Hogwarts as a kid. But you start over again, and new dialogue options appear to reflect the knowledge you gained in previous play-throughs. Every time you think, “This will be the one where I save her.” But the more times she dies, the more it dawns on you: none of this matters. She always dies in the end. Cornell says:

I wanted it to be a game where you’d be expecting there to be this nice ending, and there just never would be one. We usually start games assuming ‘They’re going to tell me a story, and it will end satisfactorily.’ That’s a dangerous assumption, I guess. I knew that I wanted to make that be a thing. The endings [players] wanted would not be there. It wasn’t until about halfway through development, though, that I realized what a potent tool that could be.

The idea was born during a conversation with Jim Crawford, another indie developer responsible for games like the wildly ridiculous Frog Fractions. Cornell and Crawford started talking about ideas for absurd dating games, like one in which you play as an alien xenomorph and the conversation trees you click on to progress include an option to eat your date and all her friends.

That led to a much better idea: a game in which you play as an NSA agent keeping tabs on someone who you have to later interact with without letting on how much you know about them. And that led to a still much better idea, when Cornell began considering elements from the Bill Murray movie Groundhog Day, like the helpless feeling of repeating the same experiences over and over.

He envisioned a game where you replay the same conversation ad infinitum, testing different tactics until you realize that what you thought was the worst option was actually the best. Cornell says:

What the game was basically doing was drawing attention to the fact that you’re playing a game by elevating the unique things that you can do as a player of a game from the weird limbo they’re usually in—where games know you can do that, but they don’t really acknowledge it, and pretend you can’t. The game fully embraced it as, yes, you’re going to reload from saved games, or you’re going to start over and try different choices, or you’re going to look at the menu options and try to figure out things about the game. It’s not like game developers don’t know you’re going to do that, but everyone pretends you’re not. So when I realized I was making a game drawing attention to that, basically that’s when player agency became the focus of what the game was going to be about.

Save the Date culminates when you’re finally able to convince Felicia that she’s a character in a video game who won’t stop dying. She brainstorms with you about how to win—how to save her life. Thing get deep. Then she gets hit by a meteor. As it turns out, there really is no happy ending. But before she dies (again) Felicia suggests that maybe the only way to beat the game is to walk away and imagine it ended however you want. Cornell says:

A lot of people said that they found it very moving as a commentary of acceptance of things you can’t change, which I can certainly see. But in some ways that’s kind of the opposite mindset I had. I thought I was writing a game about stepping outside the rules to make the changes you want to. And they viewed it instead as a game about recognizing that some things are inevitable and that maybe that’s OK. They found that meaningful, so I can’t really fault them.

Save the Date is available for free for Windows, Mac and Linux on paperdino.com.