ANIMAL’s feature Game Plan asks game developers to share a bit about their process and some working images from the creation of a recent game. This week, we spoke with Sean Vesce of E-Line Media and writer Ishmael Hope about Never Alone (Kisima Inŋitchuŋa), a lesson in “accidental ethnography.”

Until a few years ago, E-Line Media was primarily a creator of games for the classroom. Now the game developer and publisher, with studios in Seattle, New York and Phoenix, is making different sorts of educational games—ones with much narrower focus, but broader appeal.

Never Alone (Kisima Inŋitchuŋa) is the company’s first game in a new genre they call “World Games,” which “draw fully upon the richness of unique cultures.” But Never Alone doesn’t just “draw upon” the Alaska Native culture, as the game’s website states; it was co-created by Alaska Native people.

It began when Gloria O’Neill, President and CEO of the Cook Inlet Tribal Council (CITC), approached E-Line about making a video game that highlighted Alaska Native culture and traditions. The CITC is a social services group based in Anchorage, and O’Neill believed a game could help them reach Alaska’s youth, according to Never Alone’s creative director, E-Line’s Sean Vesce.

“We tried to talk her out of it initially because of how risky games are and how competitive they are, but she was really tenacious and she had a big vision,” Vesce told ANIMAL.

Before joining E-Line, Vesce accrued 20 years of experience making blockbuster video games for companies like Activision and Microsoft. So he has a pretty good idea of how risky it is to make games. But O’Neill convinced him, and together E-Line and the CITC—which eventually formed a game publisher called Upper One Games to help E-Line get the game out the door—embarked on a very unusual game development process that lasted over two years.

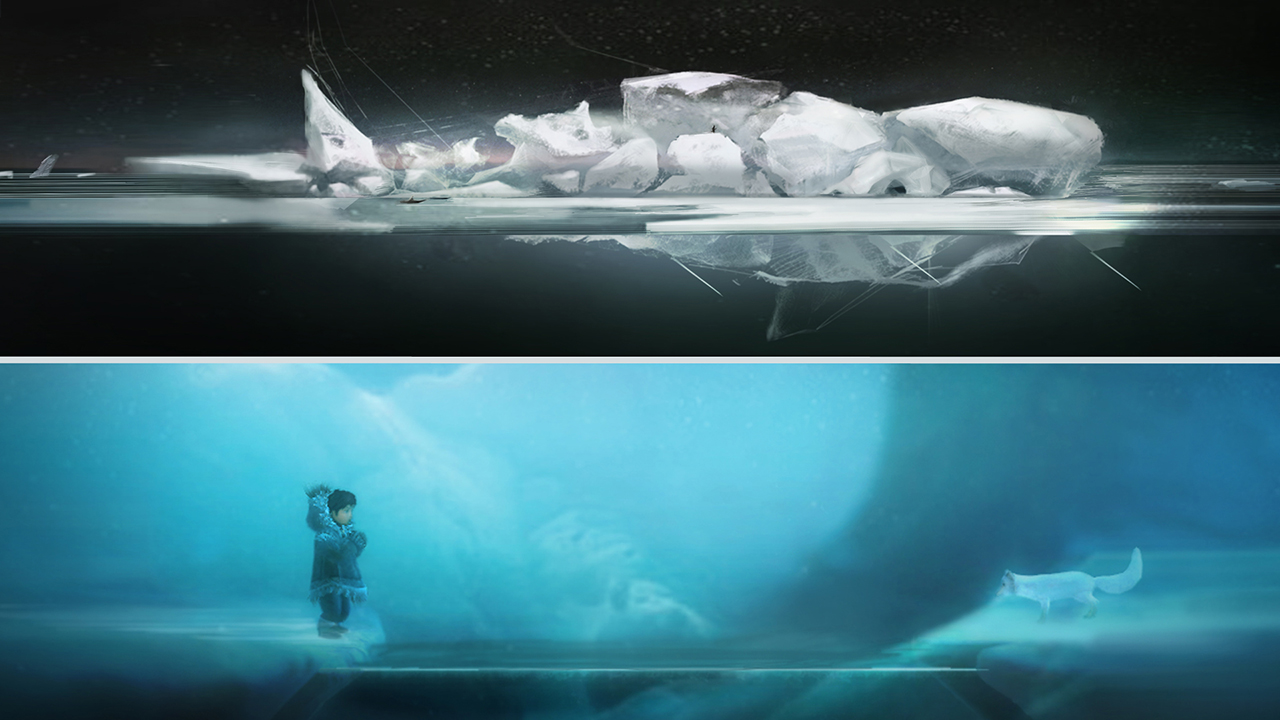

Never Alone is a side-scrolling, two-player game in which players control a young Iñupiat girl and her friend, an arctic fox. They brave blizzards, leap across floating ice fields and outsmart polar bears, earning help from the nature spirits that Alaska Native tradition holds live alongside the people every day.

The story is based heavily on the traditional Iñupiat story “Kunuuksaayuka,” a tale first recorded as being told by legendary Alaska Native storyteller Robert Nasruk Cleveland.

“Robert Cleveland is one of the greatest storytellers that ever lived in human history,” Ishmael Hope, an Alaska Native writer and poet who co-wrote Never Alone with Vesce, told ANIMAL. Hope said he wanted to “shine a light on the voice of the Elders” of his culture; and “not just those anonymous, folkloric, fairy tale, kind of, you know, bastardized Western interpretations of the Elder’s voice, but the actual, authentic voice of the Elders,” he said. “Their individual stories are as much of a literary and spiritual achievement as anything you’ll find anywhere.”

They didn’t adapt Cleveland’s story word-for-word, changing the protagonist from a boy to a girl and making other alterations. But they ran all these changes by Minnie (Aliitchak) Gray, an Elder in the community—and Cleveland’s daughter. She helped make sure the game stayed true to the story.

Not every game developer would go to such lengths, but that’s what makes Never Alone special. The developers and the Tribal Council wanted to make a great video game, but all agreed that they needed to do it without resorting to “appropriation,” as Vesce put it.

“These internalized stereotypes [about native peoples] always come up, and these so-called ‘collaborations’ that happen are very often just, native people are ‘included,’ they’re the ‘consultants,’ but the power is almost always completely out of the hands of the native people,” Hope explained.

He became involved with Never Alone in its early stages, and he was honest about his reservations. “And if that burned my bridges, that was going to be fine for me,” he said. “It’s the blood of my ancestors, you know?”

That didn’t happen, though, as O’Neill and Vesce won him over. Hope was vital to the game’s creation—as were the many other Alaska Native community members E-Line met with during development. Vesce spent the first eight months of the process traveling continuously to Alaska with various members of his team, immersing themselves in the culture.

“We felt really from the very beginning that we couldn’t just go up with drawings and, you know, describe the game,” Vesce said. “We had to show and we had to put controllers in people’s hands.” They brought the game to local schools, as well as to community Elders who’d never played a video game in their lives, soliciting an unprecedented amount of feedback.

“There are a lot of great stories of how we, as game developers, had a notion about the way a mechanic should work, but then having worked with the community realized that our worldview or our biases needed to be adjusted in order to get something that was more appropriate to the way they see the world,” Vesce said.

They went through countless prototypes. The CITC was worried about the fox character because of local youths trying to befriend wild foxes, so E-Line tried a wolf, an owl, a polar bear, and other characters before convincing the Council that the fox was the best choice. On the other hand, the Elders objected to an early version of the game that let players summon the spirit world to help them with the press of a button.

“When we brought it to community members they were like, ‘That is not the way we see the world. It’s not on demand. You don’t just conjure it,'” Vesce said. In the final game, the spirits reveal themselves to the characters on their own.

The developers also conducted dozens of hours of interviews with community members and Elders, and they eventually started bringing a film crew with them. They compiled the footage into about 30 minutes’ worth of small vignettes that can be viewed as players progress in the game. One interview subject is Minnie Gray, Robert Cleveland’s daughter. Another is Alaska Native Elder James (Mumiġan) Nageak, who also provided some of the game’s traditional music and the Iñupiaq-language voice of the game’s narrator.

“We recognized really early on that even though we brought a lot of skill and expertise as game developers, that we were really students and we were there to listen and learn,” Vesce said. “What better way for people to experience what we were experiencing as kind of accidental ethnographers than to embed that material in the game itself?”

The thing that struck me most was the level of accountability Vesce and his team clearly felt. It seems to me that most developers tend put their own designs above all other concerns, but for Never Alone that wasn’t the case.

“I’ve never felt a level of responsibility as I had on this project, and I think our team feels the same way,” Vesce confirmed. “They trusted us, and we felt that responsibility all the way through.”

Never Alone is available now on Windows PC, Xbox One and PS4.