One reason that human beings create art — whether literary, musical, or visual — is to better understand the world that we live in and how we perceive it. But what happens when that world is suddenly turned upside-down and nothing follows the rules? Struck by an ear disorder that threw his sense of reality out of balance, visual artist Rob Strati became inspired to create a new series of images that combine poetry and a universe of geometric symbols to reestablish his sense of order.

Late last year on the evening of December 21, Strati, who is 42, was completing work for an upcoming exhibition in Los Angeles. After finishing dinner with his wife, author Jocelyn Cox, one night, “We were sitting on the couch, and I felt a little dizzy, like if you get up from a chair too fast,” he explained in a recent phone conversation. “It kept happening, then in 10 minutes the room was spinning. I couldn’t see straight. From my perspective everything was shaking really fast.”

Late last year on the evening of December 21, Strati, who is 42, was completing work for an upcoming exhibition in Los Angeles. After finishing dinner with his wife, author Jocelyn Cox, one night, “We were sitting on the couch, and I felt a little dizzy, like if you get up from a chair too fast,” he explained in a recent phone conversation. “It kept happening, then in 10 minutes the room was spinning. I couldn’t see straight. From my perspective everything was shaking really fast.”

Things went quickly downhill from there. “I tried to stand up, I couldn’t stand up, I was vomiting. My wife had to call an ambulance,” Strati recalled. These were the first symptoms of labyrinthitis, a swelling of the inner ear that interferes with the body’s ability to hear and balance and causes intermittent attacks of vertigo and nausea.

Though Strati’s wife was pregnant and due in just five days, the artist could barely walk and was told it would take six weeks to fully recover. His vision was still off, but the artist dragged himself back to his studio near his home in Nyack, New York, and kept putting together pieces for the upcoming exhibition. Then Cox went into labor.

Though Strati’s wife was pregnant and due in just five days, the artist could barely walk and was told it would take six weeks to fully recover. His vision was still off, but the artist dragged himself back to his studio near his home in Nyack, New York, and kept putting together pieces for the upcoming exhibition. Then Cox went into labor.

Coping with the labyrinthitis, “I drove really slowly to the hospital,” Strati recalled. On December 28, the day his son was born, the artist woke up and began experiencing visions, images that looked something like the geometric prints he had been working on accompanied by “ideas about relating the structure of civilizations,” he said. Strati began to draw out these visions with Illustrator software and publish them on a Tumblr called “Creating Civilizations.”

“I assumed my creative process was all associated with the eyes,” Strati said. Yet the visions seemed to come from somewhere else entirely. “This inner reality was very solid, while my outer reality was completely unstable. It was like seeing from the middle of your body.”

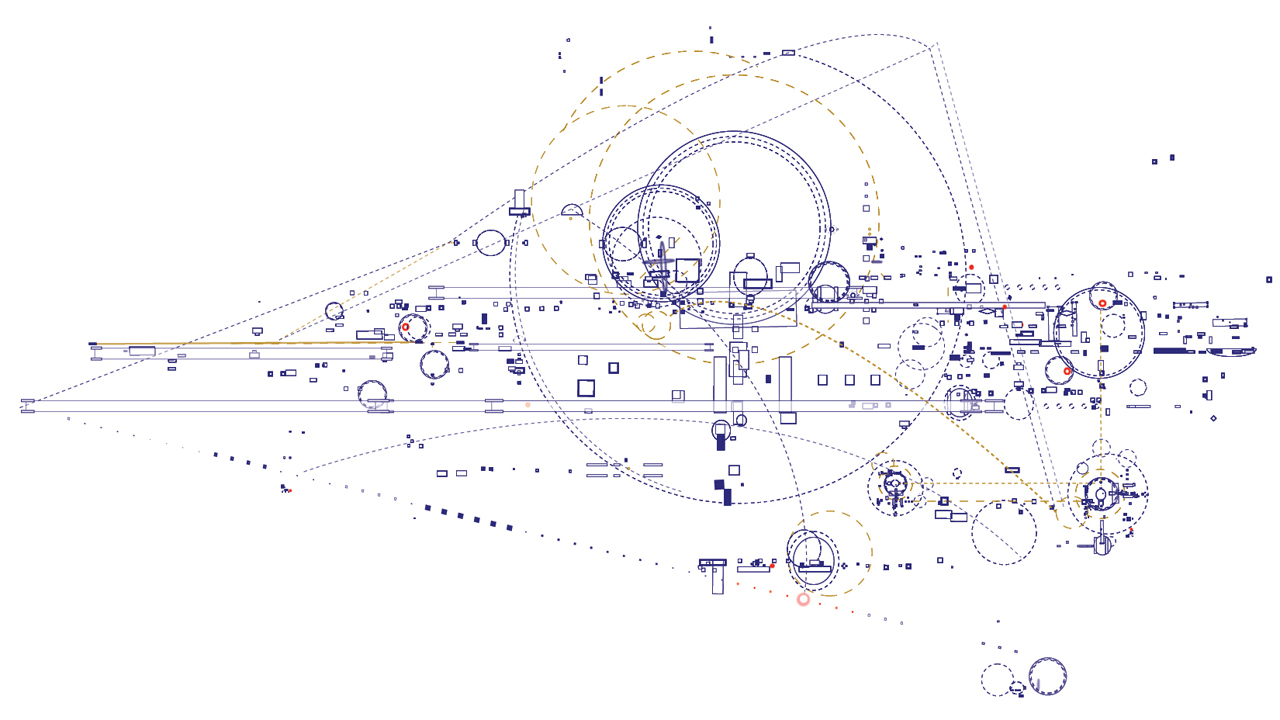

Strati’s images, symphonies of thin lines that trace out dotted circles, elongated rectangles, and sweeping curves, look like plans for a time-traveling space station or history’s most complex cathedral. The drawings spiral into fragments of graphs, charts, and timelines that hint at some grand plan or important information to be imparted, but they fall just short of disclosing what they signify.

The language of representation, how “a single dot, or a small dash, or line and curve” can “combine in different ways to represent vastly different sets of information” has always been fascinating for the artist. With just those elements, “You could write a symphony, you could draft a skyscraper, or map a solar system or the oceans,” he said. Strati also makes use of his interest in schematics with his work in user experience; he designs virtual interfaces and maps with the same software he uses to draw.

When he posts a new composition on Creating Civilizations, Strati always accompanies it with a snippet of poetry or prose. The language is formal and abstracted, often speaking to the drawing process. “In the civilizations I have created / where technology replaces speech with thought / waves generated by the mind are broadcast eloquently,” he writes in a recent post. That language, so unlike Strati’s own casual speech, came with the labyrinthitis visions.

“All these phrases kept coming to me,” he said. “This was a real clear instance of something coming from another part of yourself.” Strati majored in art history at Ohio State University, but the lyrical sentences were totally unlike the essays and reports he wrote there. He described how the Creating Civilizations project has opened up new artistic areas to explore. “It’s this space now I can kind of access to formulate ideas that I’ve been thinking of but have nowhere to express.”

“All these phrases kept coming to me,” he said. “This was a real clear instance of something coming from another part of yourself.” Strati majored in art history at Ohio State University, but the lyrical sentences were totally unlike the essays and reports he wrote there. He described how the Creating Civilizations project has opened up new artistic areas to explore. “It’s this space now I can kind of access to formulate ideas that I’ve been thinking of but have nowhere to express.”

The labyrinthitis is slowly fading (it’s about 95 percent gone, he reports), but Strati’s diagrams remain a way for him to deconstruct and understand his environment. “Creating Civilizations is an attempt to create stability in a chaotic world,” he said. “We map out these things to give us a sense of grounding and stability.”