Last week, the New Scientist published an “emotional contagion study” conducted by researchers employed by Facebook, which proved that people can be influenced by the emotions of others online, just like “in real life.” The study’s unsettling methodology caught our attention: The experiment’s subjects were nearly 700,000 regular Facebook users whose feeds were manipulated to contain more “positive” or “negative” posts without their knowledge.

Earlier, Cornell wrote in their press release that the Army Research Office helped fund the study, who, according to their website, work on “developing and exploiting innovative advances to insure the Nation’s technological superiority.” ANIMAL spoke with Joyce Brayboy of the Army Research Office who stated that the study did not receive funding from their division. She states that it received no external funding at all. Cornell issued a correction.

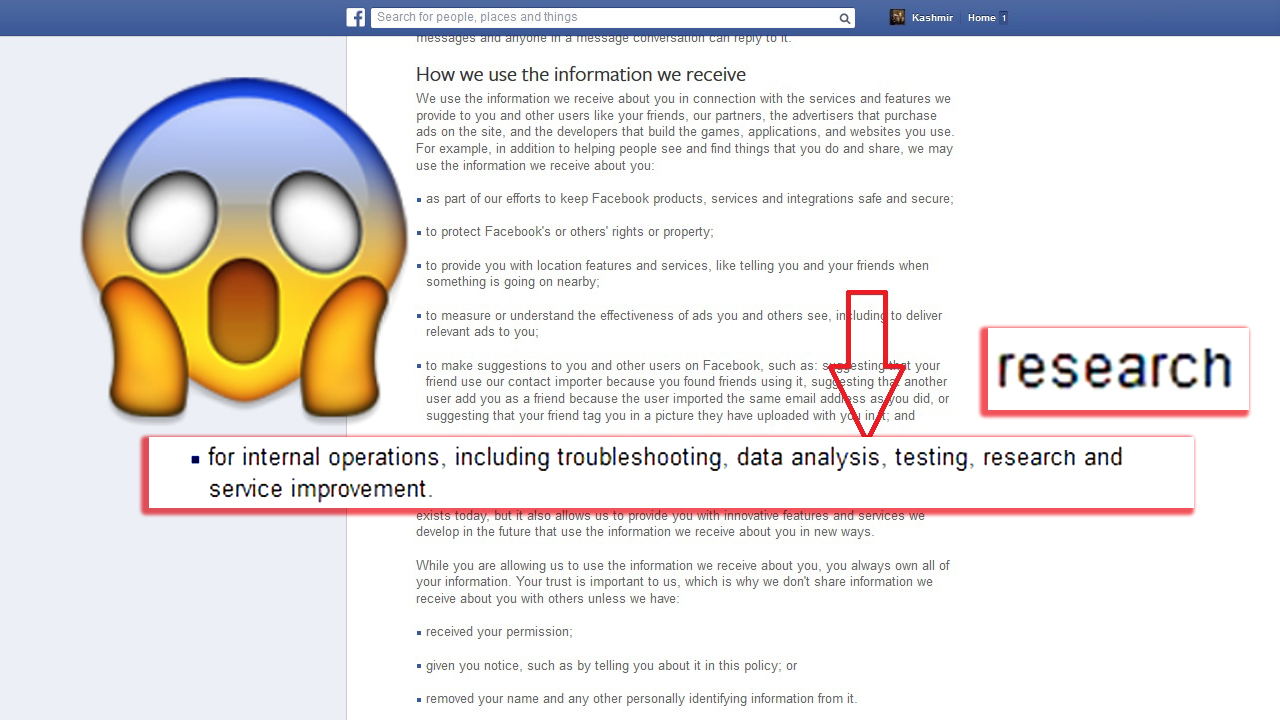

Apparently, social media manipulation of people, their emotions and allegedly private behavior for “research” is just business as usual. This particular study’s authors claimed that “informed consent” was implicit in the Facebook User Agreement which all users agree to upon signing up. Based on the massive response to this story around the world, journalists and scientists find that claim questionable at best, and that’s just the tip of the iceberg. Here’s a breakdown of the updates.

THE SCIENTIFIC COMMUNITY THINKS THE STUDY IS UNETHICAL

THE SCIENTIFIC COMMUNITY THINKS THE STUDY IS UNETHICAL

Social experiments such as this one are required to go before an institutional review board to make sure they are ethically sound. These procedures were put into place after the grievous abuses of many scientific experiments on humans in the early to mid 20th century. It turns out, this study did go under review by a board who found it ethical, according to The Atlantic. However, the board’s reason for the approval was the very fact that Facebook already manipulates our feeds for various reasons all the time and this experiment actually wasn’t out of the ordinary. This isn’t exactly the most comforting explanation, and certainly doesn’t resolve the wider ethical implications of Facebook doing this kind of work, according to the scientific community at large. Several scientists are specifically in disagreement about whether the brief mention of “research” in the Facebook User Policy constitutes “informed consent,” and many don’t think it’s good enough. Even Susan Fiske, who edited the study for publication, is unsure of its ethics. She told The Atlantic:

It’s ethically okay from the regulations perspective, but ethics are kind of social decisions. There’s not an absolute answer. And so the level of outrage that appears to be happening suggests that maybe it shouldn’t have been done…I’m still thinking about it and I’m a little creeped out, too.

THE FINDINGS ARE BARELY SIGNIFICANT

THE FINDINGS ARE BARELY SIGNIFICANT

All that “statistically significant” means in scientific terms is that the effect in question was unlikely to have occurred due to chance. Multiple sources have noted that the impact on users emotions found by the algorithm employed in this study are very small. This is not the kind of phenomena that’s going to send someone spiraling into depression. However, as noted in The Atlantic, Facebook is so huge that minuscule trends can still have major results. As was written in the original study:

Given the massive scale of social networks such as Facebook, even small effects can have large aggregated consequences. […] After all, an effect size of d = 0.001 at Facebook’s scale is not negligible: In early 2013, this would have corresponded to hundreds of thousands of emotion expressions in status updates per day.

THE STUDY IS SCIENTIFICALLY FLAWED

THE STUDY IS SCIENTIFICALLY FLAWED

John Grohol at Psych Central is skeptical of the tools used in the study’s ability to measure the results they claimed to prove. Because it was an algorithm and not a human analyzing status updates to determine whether they were positive or negative, a status that used the word “happy” would be rated as “positive,” even if the sentence said “I am not happy today.” Robots — still not great at reading the intricacies of human emotion.

ONE OF THE RESEARCHERS APOLOGIZED… SORT OF

ONE OF THE RESEARCHERS APOLOGIZED… SORT OF

Adam Kramer, one of the authors of the study and a Facebook employee, posted a public apology on his own Facebook account. Kramer mostly uses the post to clarify the intentions of the study, and only apologizes for the reaction the study caused, not for the actions of the researchers. He does say that they are working on improving their review methods and that they have “come a long way since then.”

THIS IS “NORMAL”

THIS IS “NORMAL”

Like so much outrage over big data, mass surveillance and privacy online, the average person is dismally uninformed about how commonplace these practices are. A fascinating post by “persuasive technology” researcher Sebastian Deterding provides a great rundown of the scandal’s more technical components, ultimately coming to the conclusion that many of the articles on this story are “overwrought” and that the writers of these pieces have little understanding of just how frequently research like this takes place, while researchers who have spent years working in the tech environment see this as just another in the endless parade of studies and tests companies constantly carry out on their users.

“NORMAL” ISN’T GOOD

“NORMAL” ISN’T GOOD

Research psychologist Tal Yarkoni hammers in the naiveté of anyone who was shocked by this. What he writes is important and central to the kerfuffle around this issue, which may be driven more by page view hungry journalists than by any actual scandal, unless said journalists are aware of the sheer scope of how social media and big data impact our lives.

The reality is that Facebook–and virtually every other large company with a major web presence–is constantly conducting large controlled experiments on user behavior. Data scientists and user experience researchers at Facebook, Twitter, Google, etc. routinely run dozens, hundreds, or thousands of experiments a day, all of which involve random assignment of users to different conditions. Typically, these manipulations aren’t conducted in order to test basic questions about emotional contagion; they’re conducted with the explicit goal of helping to increase revenue. In other words, if the idea that Facebook would actively try to manipulate your behavior bothers you, you should probably stop reading this right now and go close your account.

Yarkoni believes that “complaining” about this study won’t inspire positive change, instead, it will lead to Facebook becoming more hesitant in disclosing the results of the inevitable future studies. He believes this will be a loss for the scientific community and anyone who values transparency. This sentiment is unfair to journalists whose job it is to report stories like this to the public. If anything, it means that scientists like Yarkoni and Deterding should be taking a more active role in educating the public about the reality of massive online entities who are using their users as their petri dish. The more you know…