Language is constantly changing — if you were to travel just a few decades back in time and tell someone that, say, your boo’s got mad swag when she twerks in those jeggings, they’d look at you like you were batshit (there’s another one) — and that’s just within recent American English. And now, a team of linguists have identified about two dozen words — still used in varying forms by 700 contemporary languages — that date back over 15,000 years.

Language is constantly changing — if you were to travel just a few decades back in time and tell someone that, say, your boo’s got mad swag when she twerks in those jeggings, they’d look at you like you were batshit (there’s another one) — and that’s just within recent American English. And now, a team of linguists have identified about two dozen words — still used in varying forms by 700 contemporary languages — that date back over 15,000 years.

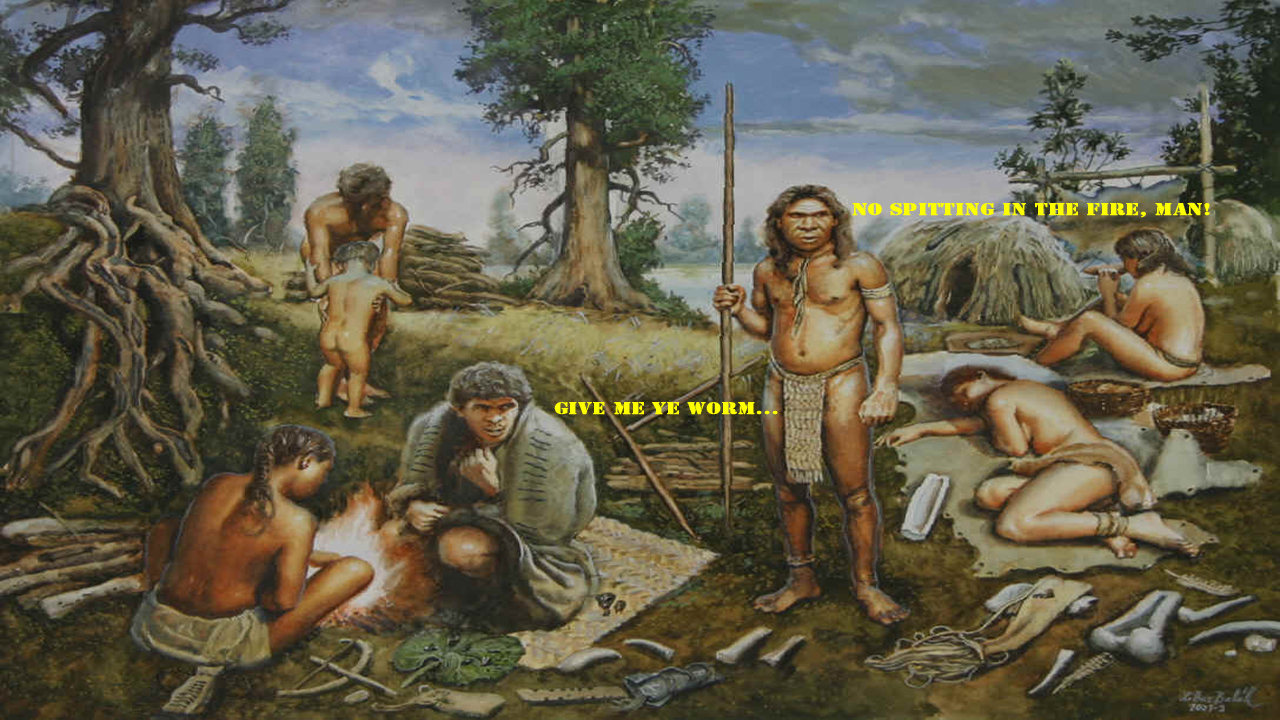

This is actually pretty incredible. Until now, the accepted linguistic belief was that words can’t outlast 9,000 years due to “weathering”. But if you were to say, for instance, “fire,” “worm,” “man,” “bark,” “spit,” “give,” “mother,” or “ashes” to hunter-gatherers in pre-Ice Age Eurasia, they’d probably have a basic understanding of your message. There are some epic implications here: for one thing, the findings suggest the existence of a never-before-identified “proto-Eurasiatic language” that lies at the root of half of the modern world’s native tongue.

“We’ve never heard this language, and it’s not written down anywhere,” said Mark Pagel, the evolutionary theorist who headed the study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. “But this ancestral language was spoken and heard. People sitting around campfires used it to talk to each other.”

The ultraconserved words also give us insight into the priorities that have been shared by humankind throughout history.

“I was really delighted to see ‘to give’ there,” Pagel said. “Human society is characterized by a degree of cooperation and reciprocity that you simply don’t see in any other animal. Verbs tend to change fairly quickly, but that one hasn’t.”