Justin Wedes of Occupy Wall Street is reporting from the front lines of the protests in Turkey for ANIMAL. He’s also tweeting from the field continuously.

I’m walking with Seda, my 18-year old Turkish translator, down Gumussuyu Street that slopes sea-ward out of Gezi Park in downtown Istanbul. She has taken me here to show me where her and her friend Selin were attacked by police a few days before, in a flare-up of the now two-week street war that has spread out of the park and engulfed the entire country of Turkey.

As we leave the festive square, the air turns eerily quiet. It’s about 3pm, and the only activity in sight is the occasional quick passing of bandana-clad, adrenaline-pumped boys in bands of five or six carrying materials to reinforce the numerous layered barricades of wood, brick, burned-out car parts, and sheet metal.

A few street vendors have set up along the road selling Guy Fawkes masks, dust masks and spray paint canisters, the hot-button items in Istanbul’s growing protest market. (How adaptive is capitalism! Would it fund its own destruction for a buck?) And it’s the spray paint I’ve come to see. I fixate on the stacked boxes of multi-colored canisters and ask Seda to translate: “Are these selling well?” Absolutely. “Are they legal?” Ehh, nothing around here is very legal. “Who buys them?” Mostly young boys, but girls also. I’m deeply enthralled.

The walls and windows of the shops and empty government buildings that line Gumussuyu Street tell the stories of the battle that went down here. “ACAB = All cops are bastards,” Seda tells me with a slight grin. She’s not a fan of the Polis, though she was more lucky than Selin when she ducked into an apartment building to escape arrest.

Selin tells me of being beaten by over 30 officers before being jailed for 3 days without food. They called her whore and threatened to fuck her on the spot. She turned off her phone because she knows how they use it to call her friends and tell them to come save her before arresting them, too. And she refused the opportunity to speak with her parents until safely in court, knowing that if she dialed them the police would take the phone, call her a terrorist before her parents’ ear and then abruptly hang up, leaving them to anguish in fear until her release. When I ask how she knows this and if she’s ever been arrested before, she tells me her friends faced the same thing days before and that many are still in hospitals recovering. She was relatively “lucky.”

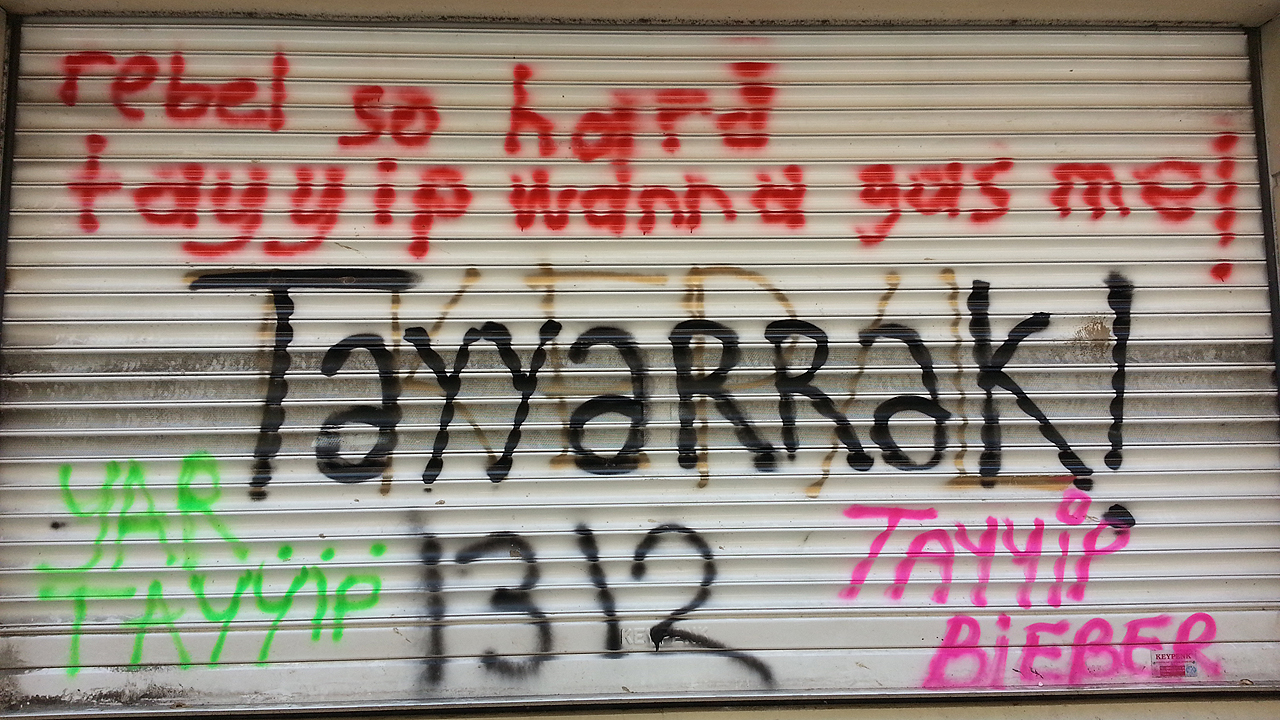

Seda’s mind is working fast now, translating each and every curse and stencil graphic and street sculpture made of uprooted bricks. For such a high-tech protest, I didn’t expect this kind of low-tech communication tool to be so prevalent. While Facebook and Tumblr are on fire with ever-evolving memes and compilation videos, the front-line fighters of this revolution are etching their tweets into asphalt.

The street graffiti seems to serve two purposes: To recount the stories of what happened here and why, and to rally more youth to the barricades. If a recent survey by academicians from Istanbul Bilgi University is any indication, it’s working: Over half of Gezi protesters are at their first mass protest. And as for communicating the stories, many of the most popular images coming out of Turkey are of graffiti art, a kind of real-time digitization of this age-old form of social media.

We approach the stairs where Seda’s friend Selin was captured by police officers who hid in the bushes after the skirmish to grab fleeing youth. Near the site, someone has dislodged a hundred street cobble stones and spray painted a happy face on each one.

On the opposite wall is a stencil of a penguin family and Antarktika Direnyor (Occupy Antarctica) written below, a playful reference to the exploding penguin meme fueled by protesters anger at the corrupt state-controlled media that opted to show penguin documentaries while street clashes raged last week. Even the barricades themselves feature messages on their sheet metal fronts, usually taunts at the police or bravado messages of strength meant to embolden the young fighters. Like the soccer chants resounding through the park, these missives are meant to raise morale and “gamify” the resistance to make it more appealing to young Turks that are new to the struggle.

Before we return to the park, I tell Seda that I’m interested in speaking to a store owner or resident on these streets which have become a literal warzone in just a few short days. Do they support the protesters? Put up with them? Quietly oppose them? We find a bearded hostel manager whose business is down 50% on European fears of travel to Turkey. Still, he holds no gripes with the protesters, though questioning their resolve: “I don’t think they’re ready for revolution. I think they’re ready for evolution.” He predicts with Erdogan’s recalcitrant return things could get ugly, though, whether the kids are ready or not.

That night, as we settle into the alley behind a luxury hotel off the packed Gezi park, another girl from Selin and Seda’s crew whips out her can and starts shaking it in a wild dance before putting spray to sidewalk: a globe and a peace sign. She hugs Selin, pulls up her bandana and heads back to the barricades to stand guard.

(Photos: Justin Wedes)