ANIMAL’s Game Plan feature asks video game developers to share a bit about their process and some working images from the creation of a recent game. This week, we spoke to independent developer Neven Mrgan about Blackbar, an indie iOS game in which players fill in the blanks of communications censored by an overbearing government.

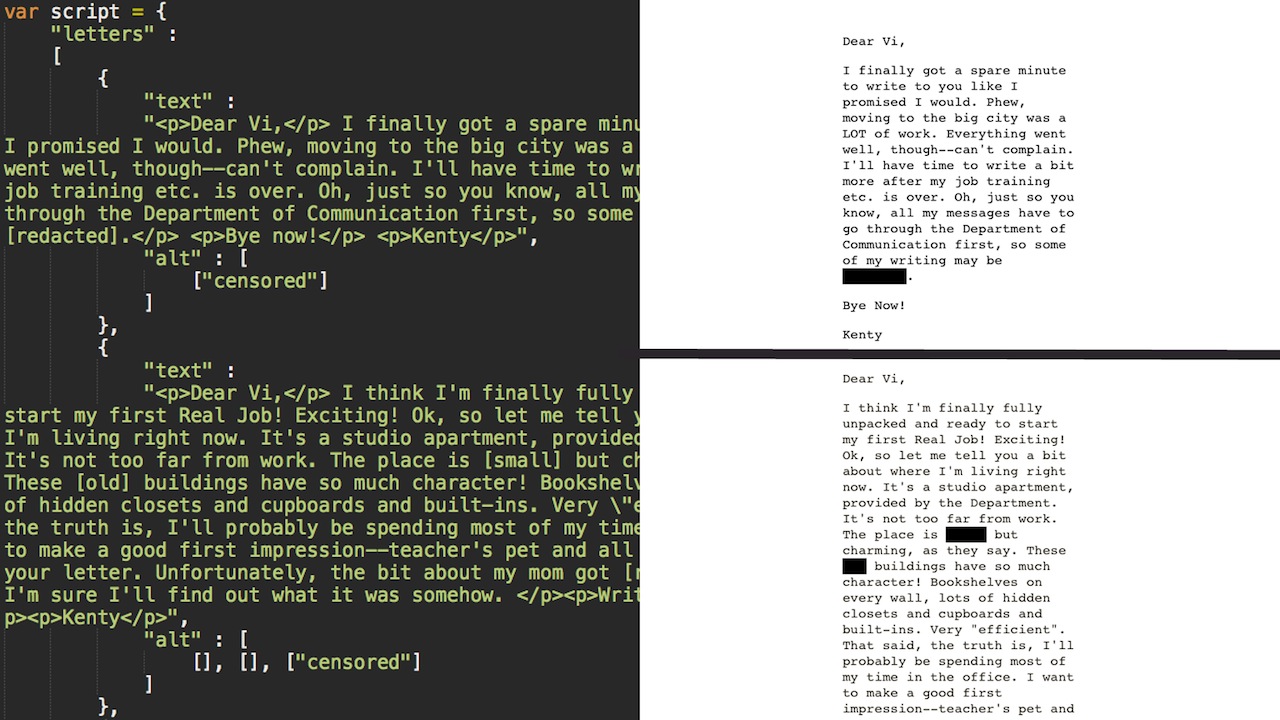

Blackbar is not a deceptively simple game; it really is as simple as it looks. Black words adorn white pages. Some of those words are obscured by disconcerting black bars, and it’s your job to fill in the blanks to figure out what’s being said. It concerns an overbearing government keen to keep its citizens from speaking freely, an underground rebel group that fights with riddles and puns instead of speeches and guns, and two friends trying to read between the lines. Designed by Neven Mrgan, Blackbar begins and ends as letters on pages, and that’s all it needs to be.

Mrgan says the game’s singular mechanic, typing in words to fill in the blanks in communications that are put through the ringer by a heavy-handed censor, came to him “in a flash.” From there it was a short leap to the dystopian setting and story.

There’s a lot of 1984 there, obviously. There’s a bit of V for Vendetta in the character of the person who’s trying to help you through [the resistance]. And then it’s also based on, in a small way, pen pals that I had when I was a kid, and that whole world: trying to understand someone just from what they write.

Playing Blackbar is like reading the inbox of someone trapped in a dystopian novel. But a small game needs a small cast, and the protagonist, Vi, receives correspondence from only five different entities in Blackbar: Vi’s friend, Kenty, who recently moved to the city to work at the Orwellian Department of Communication; a censor in said Department, whose messages to Vi become oddly personal; the neighborhood newsletter, which remains eerily optimistic in the face of totalitarian terrors; a mysterious, mixed-case “fRiEnD” in the resistance; and a neighbor named Jack. The messages are short, and it’s never clear exactly how they’re delivered. There’s a reason for that, Mrgan says.

I’m using generic words like channel, message—I don’t think I ever say device—because I wanted to strip it down completely. When I showed it to a few people they said, ‘You could make it look like it’s on a piece of paper,’ and I was thinking, ‘I really see this as a digital thing, and I want it to be arriving literally to your device, your phone or iPad or whatever.’ I wanted to make it about the text; I felt that we needed to strip away everything else.

Mrgan was born in Croatia and grew up in Communist Yugoslavia. With the country’s economy ravaged by civil war, he moved with his family to the U.S. in 1999. Now he lives in Portland, but he’s got firsthand experience with the type of oppressive regime he portrays in Blackbar.

It’s sort of like a Soviet quality: having things be the bare minimum, just geometric and unadorned. There’s something about big, oppressive government that’s always very utilitarian. I guess maybe the implication is that the [Department of Communication] in this world is actually enforcing that sort of an aesthetic. It wouldn’t be the people’s choice, but it’s like all they can send to each other is just raw black and white text.

Blackbar is short, an hour or two at most, provided you don’t get stuck for too long on any one puzzle. It starts out simple, with a single word blacked out on the first page. But that mechanic is taken to many extremes, with wordplay, visual puzzles, and even simple letter art ensuring every page presents new challenges. Mrgan says it was important for him to set up patterns he could then break.

If you set up a pattern that goes on for 30 repetitions, if you break it just once, it’s very dramatic. It punctures the thing—especially in a game that’s as small and short as Blackbar. I felt like I needed to make it feel like anything is possible in the game. Who knows? Maybe the next [communication] will be from another character. And you don’t even have to do that as long as you create, and the player has the feeling, that that’s possible. They’re going to think that the world is way bigger than it actually is.

![]()

What with certain recent goings-on, Blackbar seems particularly relevant, and that’s no accident, Mrgan admitted.

In this game the world that they live in is set up in such a way that [censorship] is just a normal part of life. And that’s always a scary thought—that something sort of sneaks into everyday life until nobody questions it. We set up a system of electric surveillance that is probably used for the exact right thing, for trying to spy on the really bad people. But once you’ve set it up, suddenly you’re spying on everyone, and the potential for abuse is just massive. The next government that comes around, the next president that gets elected, or gets put in charge of the CIA, might be a Hoover-type character who’s just going to abuse it. They wouldn’t even have to do anything extraordinary; it’ll all just be right there.

Yeah, like that could ever happen. Blackbar is available now in the iOS App Store.