ANIMAL’s feature Game Plan asks game developers to share a bit about their process and some working images from the creation of a recent game. This week, we spoke with Michael Frei and Mario von Rickenbach about Plug & Play, a short game based on a shorter film.

When I asked Swiss artist Michael Frei about the seemingly overt sexuality of his 2012 short film/2015 iOS game Plug & Play—it’s full of tiny people with electrical plugs and sockets for heads and elongated, erect fingers—he replied that he doesn’t like to answer questions about the meanings of his work. “It’s really up to the viewer,” he said, and he wasn’t just being coy.

The first spark of Plug & Play, drawn in 2011

The first spark of Plug & Play, drawn in 2011

To him and the game’s co-developer, Mario von Rickenbach, it’s more about the work’s visuals—its contrasts and binaries—and its physical, mechanical aspects. To them, the light switches, plugs-and-sockets and finger-dicks are utilitarian, although no less fascinating for it.

“I approach ‘making’ a little bit more like a designer than an artist sometimes maybe,” Frei said. His background lies partially in architecture. “It’s like fitting the pieces together in the right way, and it’s not so much about expressing myself. I mean, of course that happens, but that’s something that happens when you put pieces together.”

PLUG & PLAY from Michael Frei on Vimeo.

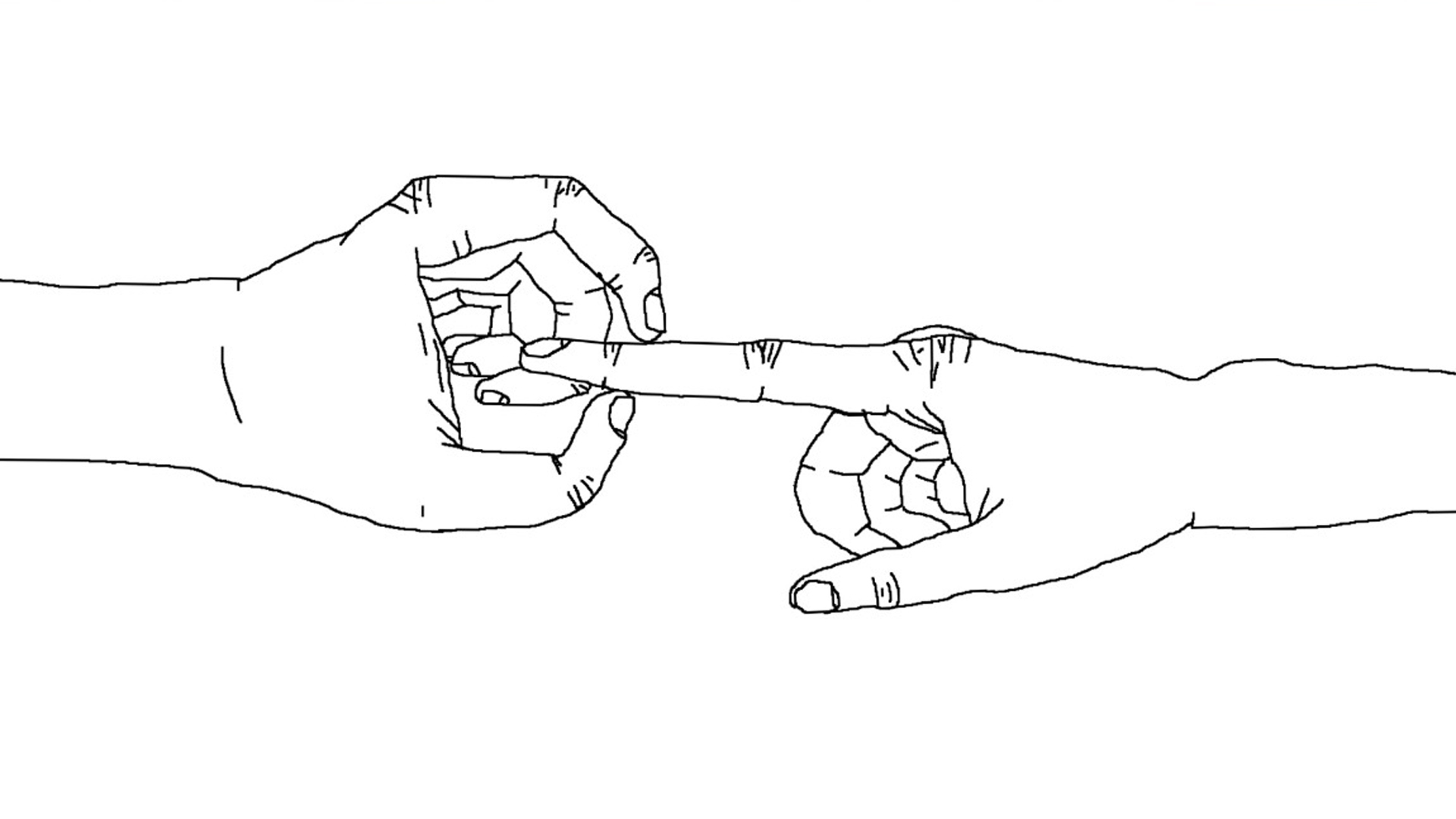

The pieces, in this case, are crude-looking black-and-white drawings of plug people, wall sockets, fingers and hands, and lightswitches, all being flicked, prodded, inserted, retracted and extended over the course of a six-minute short film that Frei and Rickenbach transformed into a 10-minute mobile game. There’s no story, only shifting facets of light and darkness and sex. The plug people chat circles around one another, arguing over who loves whom. A finger, plugged into a light switch, goes flaccid or erect when you tap the button. It’s vulgar, but in a weirdly sort of touching way.

Kill Screen’s convinced that Plug & Play is about “the hopelessness of digital communication,” but the perv in me finds it hard to get past all the penetration. “I’m aware that it sometimes can confuse people, and I like that,” Frei confessed.

Frei drew the original film, which was met with accolades back in 2012, entirely using a single finger on a laptop touchpad. His work in general is suffused with fingers, and he’s fascinated by them. But he chose that unconventional input method for a very practical reason.

Various images from development

Various images from development

“When you’re an architect you draw straight lines mainly, and that was a problem what I started to draw for animation,” he explained. “My drawings were too constructed. I’m really good at drawing straight lines; I had to figure out a way to get away from that.” But on a laptop touch pad “it was impossible to draw a straight line,” he said, and it made his work more free-flowing, if cruder as well.

He knew he wanted to develop Plug & Play into a game before he even began animating the film. That was partially because fewer than 10 percent of the people who clicked “play” on his previous short film, Not About Us, watched it to the end. “That kind of was something that had an impression on me, and I started to think of how I could tell a story in a way that people could take advantage of the interactive possibilities,” he said. And he thought, correctly, that players would be more engaged with, and more likely to finish, something interactive. It worked: Around 50% of people who’ve bought the game so far played it to the end, according to the developers’ data.

Frei is interested in game design, but he searched for six months for someone who could help him with this project. He liked Rickenbach’s other games, and the two saw eye-to-eye on Plug & Play. “When we discussed what we wanted to do as a game based on this film, we had kind of a similar direction—to apply not a traditional game genre on it, but just to really take the film as what it is,” Rickenbach said.

Making the original film took about a year from start to finish, and it took two years after that to complete the game. Rickenbach said he was surprised how long they worked on it. “I mean, I’ve made games in one day, and they were OK,” he laughed. But a good chunk of those two years was spent deciding what and where to add to the elements that were present in the film. Ultimately they did include extra bits here and there, but for the most part they just took scenes directly from the film and made them interactive. It’s a natural fit; prodding and dragging Plug & Play’s digital fingers with your own fingers is so obvious it’s almost cringeworthy.

They couldn’t have done any of it if the film hadn’t performed so well at festivals. “Every time when I was broke, I got an award somewhere, and we could continue working on [the game],” Frei said. Have the years spent turning it into a game paid off? “I mean, financially, not,” he replied, laughing. “It’s a little bit like with the project itself. I mean, there is a duality. It’s black and white, it’s yes and no. Same with the [App Store] ratings; either they give you six stars or one.”

Artistically, though, Plug & Play was an important exercise in transmedia. Frei and Rickenbach don’t really think of it as a game adapted from a film; it’s both. “If you look at it next to each other, it will be just your decision if you prefer to watch a film or to play a game, but it should be the same quality, also the same content in both media, and not one thing should be, like, a copy of the other, or the game should be like a cheap version of the film,” Rickenbach said. And when it comes to films-cum-video games, that is a rare enough thing to take note of.

Plug & Play is available from the iTunes App Store for $2.99.

(Image: Plug & Play)