Methylenedioxymethamphetamine, more commonly known as MDMA, is a psychoactive drug that makes dancing to house music extra fun. Patented by a German company in 1912 and rediscovered by hip chemists over fifty years later, it was popularized in the form of cooly-branded ecstasy pills by the pioneering club kids of the ‘80s and ‘90s and the knee-jerk reactions of the federal government. The DEA enacted emergency powers to ban MDMA in 1985, leading to a greater interest and demand for the empathogen amongst young people, like illicit alcohol during Prohibition.

Fast forward to 2015: Ecstasy, mostly in the form of powder (molly), or a crystal-like substance (moon rocks), sells for about $100 a gram and is distributed across a wide demographic spectrum, including to students, journalists, Wall Street traders, psychologists, and campers. In its purest form, MDMA is relatively safe. Unfortunately, as a banned and therefore unregulated substance, a lot of the ecstasy sold in the U.S. nowadays doesn’t contain pure MDMA, but a cocktail of various molecularly-related, yet markedly different compounds some of which tend to be more dangerous like MDA, PMA, PMMA MDPPP, MDPV, MDxx — or other drugs such as caffeine and ephedrine — that can cause adverse effects when combined.

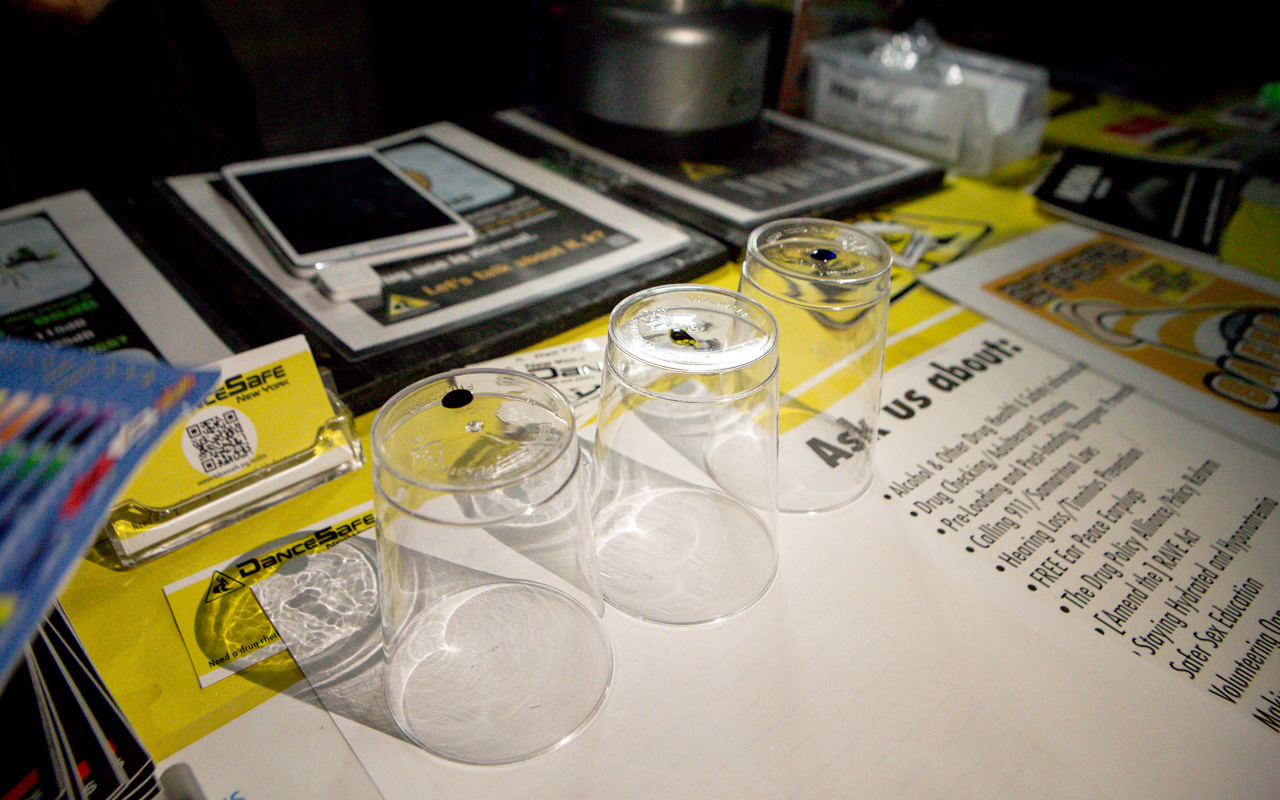

Enter in DanceSafe. Founded by Emanuel Sferios in 1998, the nonprofit takes a mature approach to drug education and is one of the first organizations in the U.S. to offer harm reduction online and IRL. DanceSafe partnered with the drug experts at Erowid to launch www.ecstasydata.org in 2001, allowing users to anonymously send in their E to be tested. The group also pioneered the use of on-site drug testing and eventually developed kits that can be used anywhere.

“Whatever is being sold in the street often has adulterants that can be more harmful to the user than the actual substances people think they’re taking,” explained Kellye Greene, a director of DanceSafe’s NYC chapter. “I would definitely say a good one third of molly that comes through tends to be not MDMA, or MDMA with something else that’s present in it.”

On a recent Saturday night in an undisclosed warehouse in Bushwick, DanceSafe set up a booth and allowed ANIMAL to document its drug screening capabilities. Using five reagents, the tests “can only determine the presence, not the quantity or purity, of a particular substance,” according to the organization. Part of that process includes the detection of harmful adulterants. Throughout the event, Greene does her best to not take possession or come in direct contact with the drug. Partygoers are asked to scrape a tiny amount of their drugs onto a neutral surface which is then tested by DanceSafe personnel. “What we find tends to kill people the most are complications from ingesting an unknown substance of unknown toxicity in higher doses than would be recommended,” said Greene.

Though it’s an important service, it’s not always one Greene is able to perform for the public. “It’s not common for us to be able to do testing because there is often an undercover police presence,” explained Greene, “so we’re afforded the opportunity at this event, because it is an underground party.” Due to the epically flawed RAVE Act that later evolved into the Illicit Drugs Anti-Proliferation Act, many promoters are reluctant to invite organizations like DanceSafe to their events. Harm reduction in the form of drug testing can be construed as promoting drug use, which is illegal under the federal statute, as are cooling rooms; in some extreme cases, glowsticks have been deemed contraband. Many health and legal experts have called for the repeal — or at the very least, an amending of the law, claiming it’s too broad and ineffective.

I asked Greene what’s the best way to protect herself from the authorities when testing drugs for other people. “Don’t get caught,” she said.

(Video: Aymann Ismail/ANIMALNewYork)

(Producer: Ilie Mitaru/ANIMALNewYork)