Imagine the following scenario: A chemistry grad student sneaks into the 3D printer lab late at night. He’s downloaded a file he got off the internet, a molecule that’s never been synthesized. It’s a modified version of an existing drug, an analogue, a single tweak on a corner of a benzene ring. The machine whirs to life. A few hours later, the machine dings. A micro test-tube slides out and a never-before-seen drug emerges. The student takes the test tube and his removable drive, but this time, the machine has added the instructions for a full synthesis. Soon the file will be in a massive chemical plant in China or the former Soviet Union. The drug will flood the market in tonnes, authorities will be scrambling and the media will have a field day.

As legislation banning the substance slowly moves forward through parliamentary procedure, another grad student steals away to her 3D-printed chemistry lab, this time with the plans of a brand new theoretical drug that has no existing counterpart. By the time the old analogue drug is banned and the police take triumphant photos of a New Jersey warehouse raid, there’s a darknet file transfer to a supposedly abandoned pharmaceutical plant along the Rotterdam-Lianyungang Trans-Eurasian Railway nicknamed the “New Silk Road.”

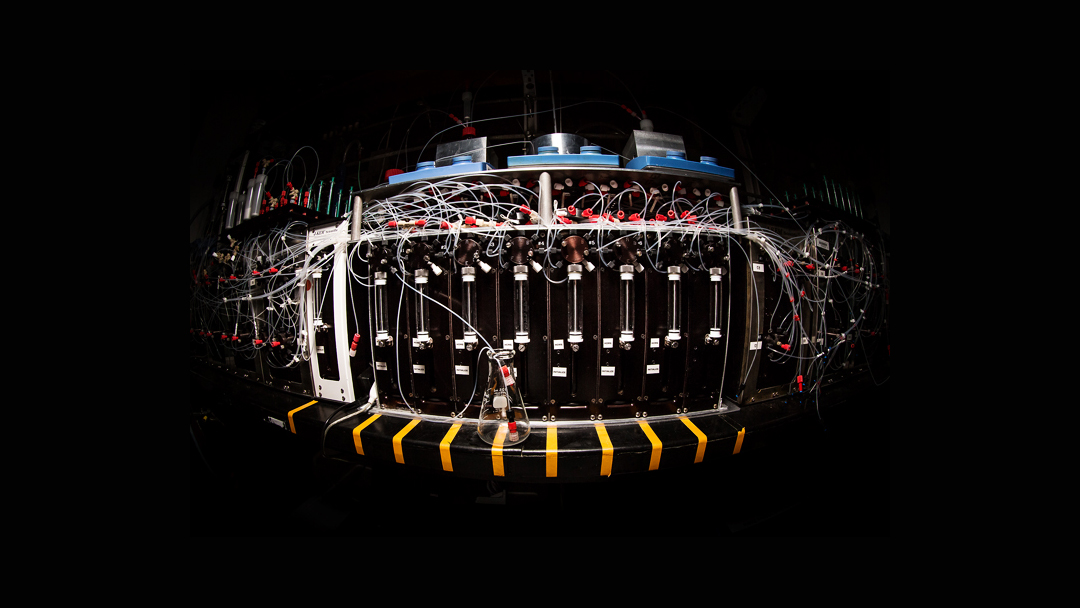

It sounds crazy now, but research by University of Illinois chemist Martin Burke may just make it our reality soon. In a study published on Friday in the journal Science, he’s unveiled a chemical 3D printer that can synthesize thousands of different molecules from a few starting compounds. The synthesis machine breaks down the complicated process behind synthesizing chemicals into generalized steps. The machine uses chemical building blocks and snaps them together like LEGO. Then, using a proprietary process, the machine can clean and purify the chemical and prepare it for the next step.

So far, Burke’s demonstrated that his machine synthesize chemicals, such as medicine, to molecules used to make LEDs or solar cells. Instead of taking years of work for a trained human chemist, the machine can do in just hours. No more digging in the jungle to get a sample of a rare plant, looking up the substances in said plant and synthesizing the chemicals you need from the comfort of the lab.

“Giving the general population the ability to synthesize these molecules would be [game-changing] in ways I can’t even imagine,” Burke said.

It’s a noble intent, but these disruptive innovations come with a lot of side effects. I don’t think that the inventors of 3D printers imagined they’d be used for 3D-printed guns. There are already lots of computer programs that attempt to assist a trained human chemist. The simplification of chemistry to a future desktop machine would empower not just chemists, but average people to synthesize new and exciting creations — and that includes intoxicating drugs.

The War on Drugs is a failure; the drugs won. The need to get high is universal, it’s “fourth drive,” as described by psychopharmacologist Ronald Seigel — the other three being food, sleep and sex. We cannot legislate our drives away. What we can do instead, then, is focus on creating a legal framework for us to enjoy intoxicants. New Zealand is leading the world in creating a legal framework by which new drugs, perhaps designed in chemical 3D printers, can be approved for sale. Portugal has decriminalized all drugs, meaning addicts are treated as medical patients, not criminals. Drug crimes and addiction have plummeted in Portugal.

We cannot stop the winds of change; they’re coming, and we should act now to create a legal framework by which we can partake, as safely as possible. If we don’t act now, technology will force us to soon.

(Photo: University of Illinois)