When a piece of stenciled art on plywood appeared in Bristol last month affixed to a public wall near the Broad Plains Boys Club, its leader Dennis Stinchcombe couldn’t be certain it was the work of Banksy. The piece depicted a man and woman staring into their cell phone screens, mid embrace, and although it bore both the visual aesthetic and wry sensibility of the Bristol-bred street art superstar, he was unable to confirm it.

All was calm until Banksy posted an image of the “Mobile Lovers” work on his website, essentially authenticating the work as his own. After that, Stinchcombe says, “This place went bananas.” Droves of people began showing up, turning the location into a pop-up spectacle.

Like all Banksy pieces, he quickly realized it’s likely worth a lot of money – money that the club, a 120-year-old youth organization, could sorely use. Since the art was spray painted on an easily removable piece of wood, he was worried it could be vandalized or worse, taken. “You need to do something, Dennis,” Stinchcombe recalls thinking, “And you need to do it now, before it’s gone.”

It took him less than 20 minutes to remove the work from the wall. He then placed it in the hallway of the youth club. According to Stinchcombe, the kids had three basic reactions. First they wondered why there was a ‘Banksy’ in their club. Then they wanted to touch it “to see if it was real.” Lastly, he says they immediately picked up on the meaning behind the art. “When they looked at it, I think every single one of them got the fact that people were looking at mobile phones and not each other,” he said. “The message is we’re all so locked up in technology and phones and texting people, we very rarely get to have a relationship with anybody. And if kids are picking that up, then Banksy has done an amazing bit of trickery with his art to make people see that.”

Stinchcombe has been working at Broad Plain Boys Club, now known as the Broad Plain Youth Project for 39 years. The organization has served disadvantaged young people in Bristol – Banksy’s hometown – since 1894, providing them with a place to socialize, play sports, have a free meal, and if need be, escape for a few hours a day from terrible conditions at home. He estimates that at the current cost of operation — about £157,000 a year — the club could be out of money within 15 months. “All the funds have been stopped from the government,” he says. “Clubs all over this country are in jeopardy.” Banksy left the piece just steps from the club’s entrance. Is it possible that he intended it as a gift?

Bristol Mayor George Ferguson and city council didn’t think so. Shortly after Stinchcombe took the piece down, Ferguson called him a “thief” and disputed his ownership claim, demanding that it be removed from the club and taken to the local museum. The authorities showed up and hauled it away. “The police gave me my evidence slip, explained Stinchcombe. “The reason for removing one Banksy on plyboard is for security and safety reasons and will be secured at Bristol Musuem until ownership is established,” he recalled as if he was reading the exact words off the police report.

News outlets picked up on the rivalry and a second wave of media interested started flooding in. Knowing how beneficial the sale of a Banksy could be for his club, Stinchcombe remained hopeful, but knew it would be an uphill battle to regain custody of the work.

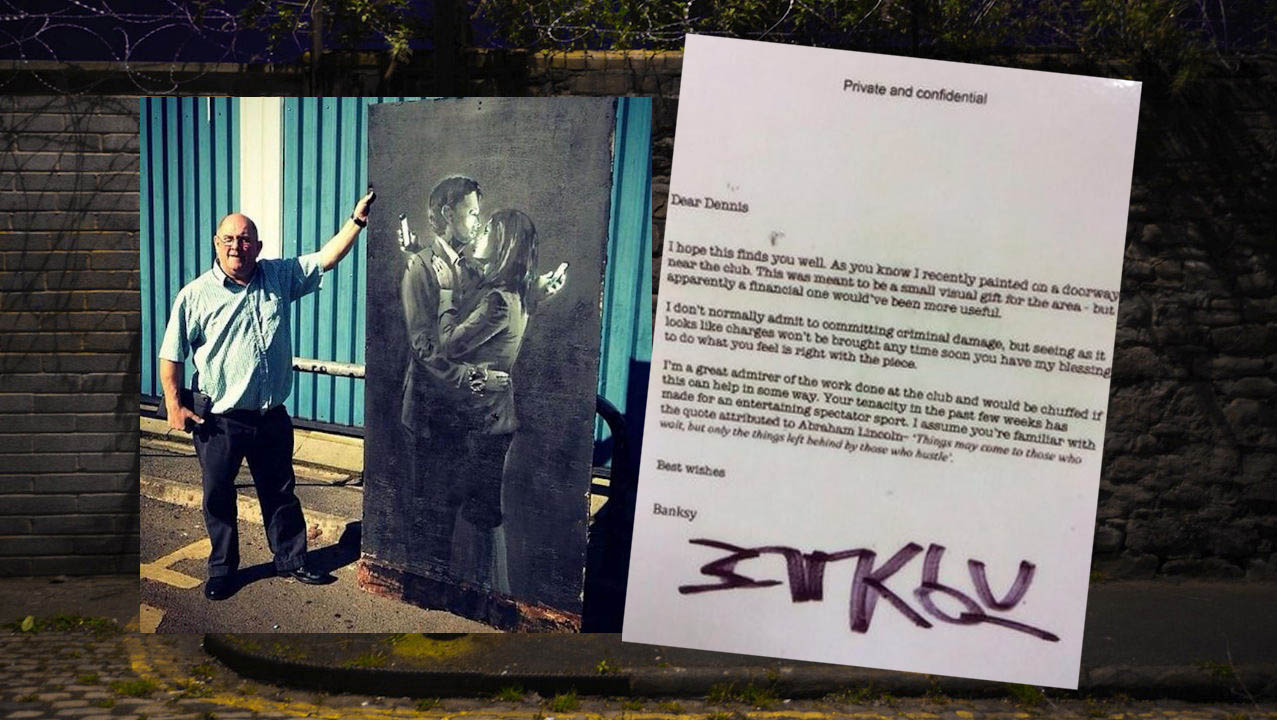

Then something very unusual happened. Stinchcombe said someone from Team Banksy dropped off a letter addressed to him. The person had slid it under the door of the club. It said:

Dear Dennis,

As you know I recently painted on a doorway near the club. This was meant to be a small visual gift for the area – but apparently a financial one would’ve been more useful.

I don’t normally admit to committing criminal damage, but seeing as it looks like charges won’t be brought any time soon you have my blessing to do what you feel is right with the piece.

I am a great admirer of the work done at the club and would be chuffed if this can help in some way. Your tenacity in the past few weeks has made for an entertaining spectator sport. I’m sure you familiar with the quote attributed to Abraham Lincoln: Things may come to those who wait, but only the things left behind by those who hustle.

The signature at the bottom, in the artist’s distinctive handstyle, read “BANKSY.”

For those familiar with how the street artist operates, this was extraordinary. Banksy never authenticates the pieces he illegally puts on the street – apart from posting images of the work on his website — as it would be tantamount to an admission of guilt. He also typically shuns the sale of his unsanctioned outdoor work. That’s one of the main reasons why Pest Control was established back in 2008. By refusing to certify the art, many large auction houses won’t touch it.

Stinchcombe informed the mayor of the correspondence who in turn, contacted Pest Control, Banksy’s in-house verification agency. Ferguson then publicly announced that Banksy had settled the dispute and as far he was concerned, Stinchcombe can do whatever he wants with it, a position ANIMAL advocated before the letter arrived.

“First, he apologized for calling me a thief,” Stinchcombe says. Then, the two men agreed to keep the piece at the Bristol Museum for safekeeping until a buyer is found.

The fact that the work is certified by Banksy himself – a rarity for street pieces – significantly increases its value, and Stinchcombe is hoping to sell it for at least £1 million. Last year,

Banksy’s “Slave Labor” art, which was chiseled out of a wall and sold at a private auction, fetched $1.1 million. More recently, a Banksy removed from a Brighton Pub sold for $575,000. However, neither of the works were validated by the street artist.

Stinchcombe says that Julien’s Auctions in Beverly Hills, which has a history of selling unsanctioned Banksys, told him they could sell “Mobile Lovers” for about $4 million, an offer he flatly refused. “Stuff the 4 million,” Stinchcombe says he told them. “You’ve upset Banksy, therefore I can’t have business with you.”

He has also received lots of angry responses from Facebook users and numerous death threats, which he brushes off with a laugh. “I just come back from a triple heart bypass operation and you think I’m worried about death?” I run a boxing club. Come down here. We’ll scrap in the boxing ring.”

As for the £1 million offer that was widely reported by the media, Stinchcombe said the buyer quickly retracted it and in the end, would only pony up £200,000. But that’s fine, because he has another buyer in mind: Sir Richard Branson, the billionaire founder of Virgin Group. The mobile phone-centric nature of the piece makes sense for Virgin, Stinchcombe says, and Branson “likes stories like ours, which is a David and Goliath story.” He even asked supporters to tweet at and message Branson on Facebook to help convince him how smart a marketing (and PR ) play this would be.

Although Stinchcombe was open to the idea of turning the image into a print and have the proceeds benefit the club, he ultimately is hoping to just sell it to one person and let that new owner decide its fate. To help ensure that the club gets the best price, Stinchcombe says a “steering committee” has been set up to facilitate the sale. Whoever buys it, will also get the letter, which is by far one of the oddest certificates of authenticity ever.

Regardless of what “Mobile Lovers” ends up selling for, Stinchcombe says he’s eternally grateful for Banksy’s charity: “I think the guy is an absolute diamond. What’s he’s done for us, and what he’s doing for young people in Bristol, is one of the most fantastic gestures that could ever happen in this moment in time.”